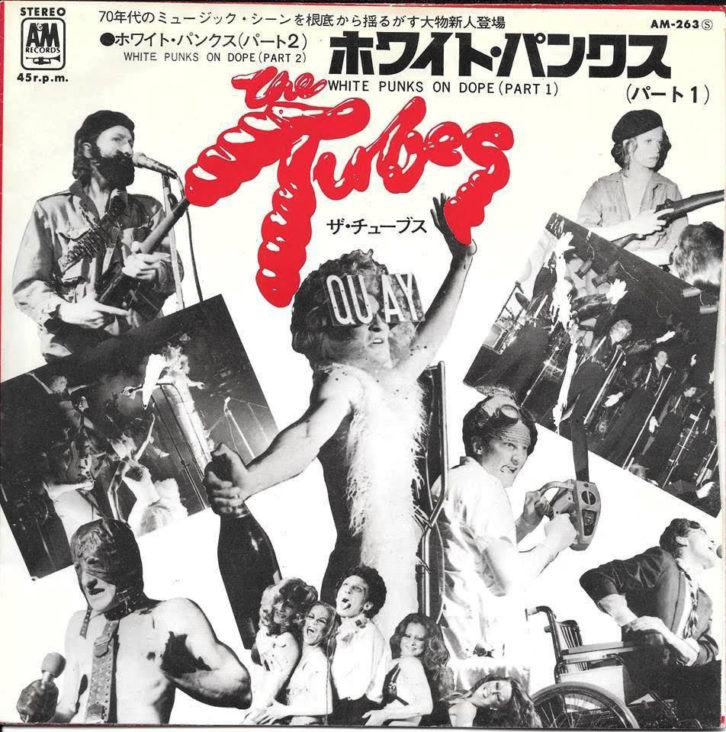

There are a few bands that have been fortunate to have created true rock and roll anthems. The Tubes are one of them. The first single from the group’s debut album, The Tubes, was the satirical and outlandish “White Punks On Dope,” released on A&M in June 1975.

The band had emerged following the conjoining of two Phoenix-area bands, The Red White and Blues Band, featuring drummer Prairie Prince, guitarist Roger Steen, bassist David Killingsworth, and their roadie, a former hippie cowboy named John Waybill, known to his bandmates as Fee, short for “Fiji,” in recognition of his mane of curly hair. The other band, The Beans, had guitarist Bill Spooner, bassist Rick Anderson, keyboardist Vince Welnick and drummer Bob McIntosh. Prince moved his band, which had changed its name to“Arizon, to the Bay Area in 1969 so that he and his friend Michael Cotten could attend the San Francisco Art Institute.

Spooner’s band followed in summer 1970, moving in with their pals at a small two-bedroom condemned bungalow (dubbed “The Noriega Hilton”) at 48th Avenue and Noriega Street in the city’s Sunset District. Arizon spent four months playing at the Expo 70 World’s Fair in Japan, then upon their return fired Killingsworth and were without a bass player.

After an unfruitful search, Spooner and the bands’ managers suggested merging the two groups into an “Arizona superband,” still performing as The Beans. Waybill, who had begun covering for Killingsworth’s lead vocals, was brought to the front mic. “They said, ‘You sing so damn loud, why don’t you sing lead then?!” he recalls.

At Spooner’s urging, Cotten purchased one of the first ARP 2600 synthesizers, initially to add sound effects to film soundtracks at school. But soon he began playing with the band, sitting near the console at live shows, adding effects to various songs and processing Spooner’s guitars via a patch from the stage.

The band quickly became known for its theatricality, creating characters and their own costumes. “I suggested we let Fee sing a few songs—we could dress him up,” Spooner remembers. After a show in which Waybill dressed as Carmen Miranda, complete with fresh fruit on his head, belting out “Brazil,” Spooner recalls, “We went, ‘This is a thing! This might work!’ So we kept it.”

One night in late 1972, Spooner and Evans were attending a party at Prince’s apartment when Evans told the guitarist about an article he had read about recording artists coming to San Francisco and recording with The Jefferson Airplane or The Dead.

“He said, ‘They smoked a lot a pot and had ashtrays full of cocaine. And it was just a bunch of white punks on dope,’” Spooner recalls. “Then he said, ‘That’s a great song title, don’t you think? Let’s sit down and write some lyrics for it.’ The apartment was so packed, the only place we could find was underneath Prairie’s kitchen table.”

The next morning, they presented their unusual lyrics to the band, in the back bedroom at the Noriega Hilton, where their manager had his office. “We woke up and Bill was all excited—they had stayed up too late and come up with this idea, but they didn’t have any music,” Steen remembers. “It had a shocking title, so we all went, ‘Oh… what?’” Steen had what would become the chorus melody as a riff, “kind of a blues tune, ‘Don’t let my paycheck down,’” he sings to the tune of “We’re white punks on dope.” The band rehearsed the song, as they typically did, in the basement of the house, and began playing it not long after, the song finding its long, jammy extension as time went on. “We’re in a band house, playing all day every day,” Steen says. “We had tons of parts trying to find a place for.” The “We’re white punks…” answer phrase soon became an anthemic chant from fans at shows.

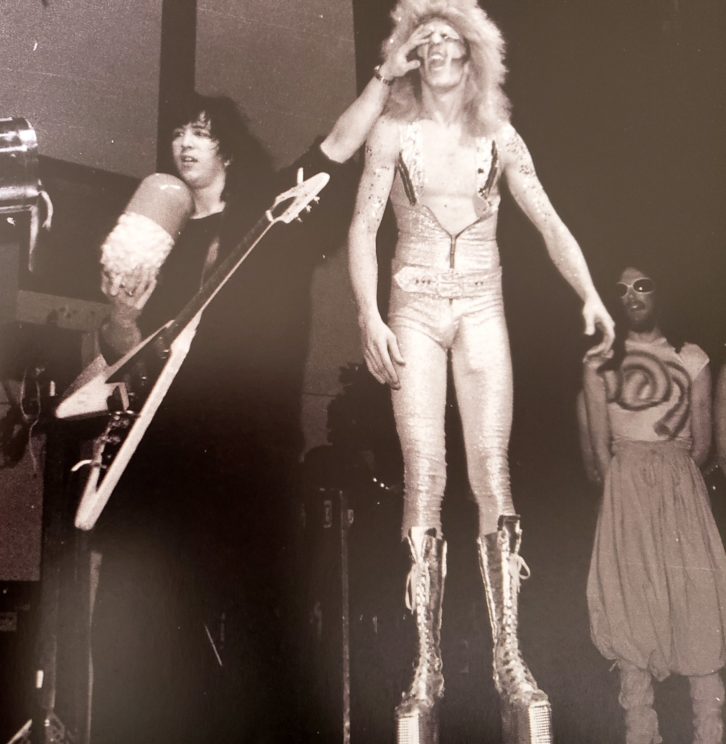

The character delivering the song was one called “Rod Planet,” a cross between Rod Stewart and Robert Plant. “I wanted to do the quintessential cross-dressing rock star drug addict,” Waybill explains. “So I had this big wig, effeminate clothing and big shoes.” Rod evolved further on September 5, 1973, the first night of a three-night stand at The Matrix opening up for The New York Dolls. The Dolls showed up for soundcheck in full regalia—hair, makeup, women’s clothing, and BIG platform shoes. “I thought, ‘God, this is so pretentious,’” he says, “Well, I’ve gotta take the piss out of them.”

So Waybill went out and got four giant tomato juice cans, emptied the juice, and taped the cans to his boots with gaffer tape, covered it all with glue and sparkles. You know, 10-inch platform shoes! One of the Dolls, he thinks, also slipped him a Quaalude before he went on. “I was completely whacked!” Rod Planet thus became Quay Lewd, Waybill eventually adding other pieces to his spandex costume—including an 8-inch rubber dildo, hanging out from his crotch.

The band, by the way, had, a few months before, been forced to find a new name. “We were in that same back room, and somebody brought in an album by some group from the Northeast, called Beans,” released the previous year, says Steen. Adds Prince, “It had a cartoon on the front cover of a guy eating beans, until they were coming out his ears.” So the fellas went through the laborious process of trying to find a name, writing on a blackboard names like “The Radarmen From Uranus” and “The Comic Ozzies,” among others. Cotten had suggested “Tubes, Rods and Bulbs” (based on parts of the eye), which was thrown into a hat, along with 100 others. Cotten’s apparently had been treated with mayonnaise – a favorite of house dog The Husky Baby Sandwich, who then pulled it out of the hat. The Tubes it was.

Recording ‘Punks’

The Tubes had been sending out demos for a couple of years, typically with the same results. “They’d send them back,” says Spooner, “and if they’d had emojis back then, it would be a guy scratching his head: ‘What the fuck is this? Are they a show band? A punk band?’” A video demo, made with the help of choreographer Kenny Ortega, was made, drawing the attention of A & M Records A & R man Kip Cohen, who scouted the band at a gig in San Francisco. Not long after inviting Prince and Cotten to come paint the outside wall of A & M’s large studio building with flying records in Fall 1974, they were signed to the label. “I think it was a case of, “Okay, you take ‘em, because you need a weirdo band,” Spooner notes.

Producer Al Kooper had wrapped up work on the latest Lynyrd Skynyrd album, Nuthin’ Fancy, in early 1975, and, looking for his next project, queried a friend, Dorene Lauer, who worked with Cohen at A & M, to see if there were any acts in need of a producer. Kooper had actually heard one of The Tubes’ demos a few years earlier and loved it.

Kooper flew to San Francisco to see meet with the band at a rehearsal stage at S.I.R., where they played him a selection of songs from their stage act. “I knew nothing about what that was like,” he says. “I based it solely on their music, which I just thought was incredibly original. People were going to have to hear this and want to go see them, without knowing what they were going to see. And when I watched them rehearse, I was floored.”

The producer selected eight songs—including “White Punks on Dope.” Kooper returned to L.A., the band coming down in early March 1975. They then began additional rehearsals and rundowns with Kooper at The Record Plant, where the album was to be recorded, practicing in the studio’s then-unfinished Studio C.

The first thing Kooper addressed was getting the band members to learn their parts. “We would play him a song, and he would say, ‘Okay now just the drums and bass play the song,’ and we couldn’t do that,” Spooner recalls. “It was the first time we had realized everyone had to individually learn their part—and play it the same way, take after take. So that’s what I learned from Al Kooper.”

Kooper had been a regular visitor to both Record Plants, and he had been to the Los Angeles studio ever since attending opening day in 1969. To engineer this project, he turned to studio veteran Lee Kiefer, who started there in 1970, earning $40/week as a janitor, eventually creating a training program for new engineers.

Early in 1975, Kooper was visiting the studio’s Sausalito facility, where Kiefer was at work on another project, and asked for Kiefer’s help with something. “He had come from Atlanta, where he had recorded Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Nuthin’ Fancy album, that he had engineered,” the engineer recalls. “It sounded as big around as a peanut—it sounded absolutely terrible.” While there, Kooper also played Kiefer The Tubes’ demo, and he was immediately smitten. “I was really excited about The Tubes. I definitely wanted to do that album. And Al said, ‘Well, here, if you can fix this [the Skynyrd album], you can do The Tubes.” Kiefer did both. “Lee was incredibly competent,” says Kooper. “He was able to do anything I wanted.”

The sessions began Monday March 17, 1975, with Don Wood assisting, recording into the middle of the following week, March 26, tracking four songs: “Mondo Bondage,” “Space Baby,” “What Do You Want From Life,” and the album opener, “Up From the Deep.” There was an 11-day break, before they returned to work, during which Kooper finally got to see the band perform live, at a surprise showing at The Palomino Club in North Hollywood. The band, just for laughs, played one of their favorites, Marty Robbins’s “El Paso,” in which Waybill would feign being the victim of a gunshot, squirting fake blood all over the audience, while leaning up on one arm on the floor, continuing to sing. “We actually won!” he laughs. “They gave us a little plaque.”

They returned on April 7 for another 10 days’ work, recording the remaining four songs, including “White Punks on Dope,” whose basic track was recorded on April 8.

The band was set up in the smaller Studio B, perfect for the tight sound Kooper was looking for. [They couldn’t have used the larger Studio A anyway; The Eagles were busy recording One of These Nights with Szymcyk.] Prince’s Rogers drum kit, complete with two kick drums, two rack toms and two floor toms, and snare, was placed in the isolation booth at the back of the narrow, long live room. “I bought that kit when I was 16, at a big music store on Central Avenue in Phoenix, from money I earned mowing lawns,” the drummer says. “Bill Spooner’s son still owns it; I sold it to him in the 1980s. And he became a great drummer, with that same kit.”

Kiefer miked the set with EV RE20s on the kicks, a Shure SM56 and, suspended by its cord, a tiny Sony ECM-50 lavalier on the snare, and Sennheiser 421s for overheads, pointed crossways from each other, to help cancel the remaining drum sound. But the reason Prince’s drums have such a powerful sound on this album is one additional trick. “I needed that ‘shotgun’ sound out of them,” the engineer explains. To accomplish that, he removed the heads from the kicks and toms, and suspended small radio speakers across the openings. “So when he hit them, I could enhance those with EQ to make the strike louder. And that gave them a bigger, expanded bottom and a louder strike, which made the drums sound huge.”

Spooner and Steen’s 40W Fender Super Reverb amps were set up, midway back, in two of the right-hand studio walls’ sound trap coves, which were stuffed with absorbent material, for isolation. Spooner played his Gibson Flying V, purchased, he says, at Lederman Music in Phoenix in 1969.

The amps were miked with Shure SM56s or 57s, as well as recorded direct. “I need to be able to control the clarity of the guitar, which I can do using the direct signal,” Kiefer explains. He also used some SHS (sample-and-hold signal) noise gates, made by a friend in San Diego, who loaned them to Kiefer to try out. “I’d place those right between the mic and the console,” so there’s no chance to pick up any noise in the line. And when the guitars weren’t playing, those channels were not turned down, they were off.”

Welnick played a smaller Yamaha grand piano, located between Prince and the guitarists, blanketed off and miked with Neumann U47s. And Anderson’s Fender Jazz bass was played through an Ampeg B15 bass amp, and recorded both direct and miked with an RE20, with it’s low-pass rolloff on, to get rid of any hum.

The band tracked “White Punks,” as they did the whole album, live, with Kooper mainly focused on nailing the bass and drums. “That, I wanted perfect,” he says, “and the rest could be overdubbed, if they wanted to replace any parts. I’d make sure that was correct, and then we’d all listen, and I’d say, ‘Okay, anybody got any grief with their parts?’”

Either Steen or Waybill would typically sing a guide vocal, but, of course, for “White Punks,” it was the latter. And when it came time for tracking his final vocal, during several vocal overdub days, he did it in a single take, Kiefer recalling him moving about, essentially performing the vocal as he would on stage. “He didn’t have a mic technique—it was a performing technique,” the engineer recalls. “He would actually perform the song as he was singing. And there was no problem with him being off-axis. His voice was so loud and clear, with a high SPL—he could sing right through the side of a battleship if he had to. He is just a magician with his voice. He’s amazing.” As for the single take, Waybill says, “I just started off, and I never stopped. I remember saying, ‘Okay, that’s it. I’m done. I’ll never beat that.’”

Cotten also overdubbed his synth parts, recorded in the control room, utilizing both his ARP 2600, as well as another larger system he had developed from parts of another 2600. “Anything musical or chromatic, that was either played or invented by Al, or even Vince,” he explains. “Anything that was an effect or dramatic sound effects or processing, that was me.” He and Kiefer worked together to create the sounds of rockets “crucifying Quay,” the engineer notes. “I worked hard to give those a power and a clarity, to make sure they have the effect of being right in your face. It’s a trick of clarity; you have to get rid of all the noise, without losing any of the dynamic of the instrument.”

For the loud trademark chant of “WHITE PUNKS ON DOPE!” sung in response to Waybill’s voicing of the phrase, in the chorus in the voluminous buildup later in the song, *everybody* was drafted in – including Glenn Frey and a few of his friends from across the hall. “I remember thinking, ‘What a ridiculous and wonderful song this was,’” Prince recalls, “and how much Glenn couldn’t wait to sing on it.” Though Steen also notes, “I remember they were kinda not fully thinking that this was the coolest thing they’d ever done. But they were into it, they came in for a few minutes and did it, and that was that.”

When it came time to mix at the end of April/early May, after some orchestral overdubs by Dominic Frontiere, Kiefer made use of a technique that had been passed down to him from Phil Spector, via Gary Kellgren—cascading tape echo. A vocal, say, was played back and recorded onto an Ampex 440 4-track machine, onto the first track, and then its return, via mults at the patch bay, would send the delay return both to a channel on the desk and onto the second track on the machine, and so on, eventually using all four tracks. “And you can pick any or all of four of those channels of return to apply to the mix,” Kiefer explains, to pan as desired. In addition, he utilized ADR Panscan to make perfect pan bounces, producing unique and impactful tape echo effects.

“White Punks on Dope” finishes the album. But Kooper added a couple of finishing touches, including effects sounds by Cotten, a stereo toilet flush (“That’s both the men’s and the women’s heads,” says Kiefer), followed by a raucous laugh, and then Japanese voice-over, lifted from a TV show taped at Arizon’s appearance at the Expo 70 World’s Fair five years earlier.

The laugh, though, is taken from one of many recordings Prince would make of his father, who was beloved by the whole band. “He liked to drink gin and sing songs and tell stories,” the drummer recounts. “So we would just sit down, and we’d record him. I played those for Al, and he said, ‘We gotta put that at the end of the record,’ a big laugh following the toilet flush, as if something naughty was being disposed of. So what was the big joke which produced the laugh? “It was the unforgettable ‘piece of pie’ joke.” Whatever that was. . .

The end product, says Kooper, “was definitely the most complicated record of any record I ever did.” Kiefer agrees. “’White Punks’ is, I think, my greatest engineering feat, especially in the day I did it.”

To this day, The Tubes still, 45 years later, close their show with the song. And they have to. “It’s amazing,” says Waybill. “And it’s still the song where I can’t wait to go out and do it, and hear people sing ‘WHITE PUNKS ON DOPE!’ They all go crazy when we play it, and they wait for it. There’s something anthemic about it, and we knew it when we started doing it. I said, ‘We’re gonna play this till the day we die.’ And we pretty much have.”