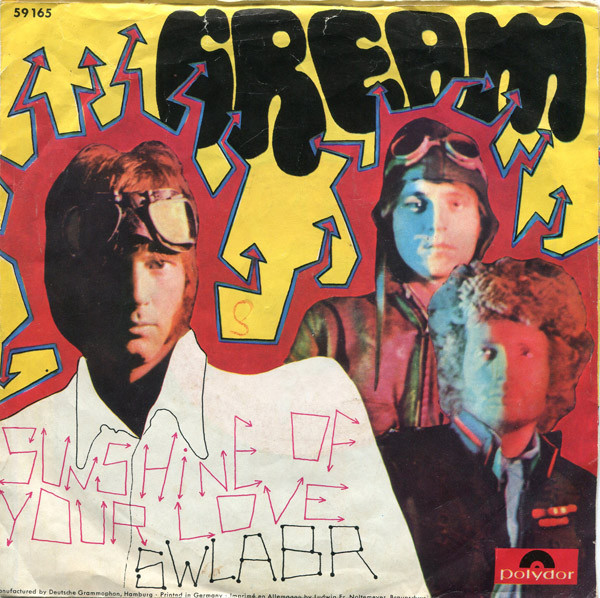

Cream was one of the first nonorganically created rock supergroups of the 1960s. Music business entrepreneur Robert Stigwood contracted Eric Clapton, bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker to play as a group, for a term of two years, with an option for a third. Each member had already achieved a degree of fame in their native UK — Clapton with The Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers; Bruce and Baker had played together in the Graham Bond Organisation; and Bruce had played briefly with Clapton in the Bluesbreakers and with Manfred Mann. Individually and collectively, they were part of a movement that was reinventing and reinvigorating American blues, electrifying it, fusing it with rock and shipping it back to the U.S., where it wound up making white British rockers far more money than it ever made for Robert Johnson.

Cream’s debut LP, Fresh Cream, on Atlantic Records in the U.S. and distributed by Polydor globally, was predictably laden with blues tunes, but also showed a deft pop hand at work. But in the wake of that record, and in the process of defining themselves beyond Stigwood’s prenuptial agreement, the band began writing more of their own material, particularly Bruce, co-writing with lyricist Pete Brown. Those efforts laid the foundations for the power trio and added immensely to the canon of psychedelic rock that Jefferson Airplane and other San Francisco Bay Area groups had inaugurated. That was the petri dish from which “Sunshine of Your Love” — which, in January of 1968, would become Cream’s first U.S. Top 10 hit — was born: a stew of blues, rock and a little bit of “Blue Moon” thrown in for good measure.

Atlantic founder Ahmet Ertegun saw Clapton playing with one of the label’s artists, Wilson Pickett, in a blues club in London in 1966. He made the deal with Stigwood to put Cream on Atlantic in the States and asked Tom Dowd, who had been ripping up the charts with other Atlantic artists, to produce the band’s second record, Disraeli Gears.

Atlantic founder Ahmet Ertegun saw Clapton playing with one of the label’s artists, Wilson Pickett, in a blues club in London in 1966. He made the deal with Stigwood to put Cream on Atlantic in the States and asked Tom Dowd, who had been ripping up the charts with other Atlantic artists, to produce the band’s second record, Disraeli Gears.

“We knew the band had basically been put together by Stigwood and that the members didn’t have personalities that always meshed perfectly,” Dowd recalls. “But I also knew they were brilliant musicians and that they would not let that interfere with their professional obligations. So I was up for it.”

Dowd was waiting for them at Atlantic Studios, on 60th Street in Manhattan, on a Thursday in 1967. He had designed the facility himself, in 1959, mainly to accommodate the Ampex 8-track deck he had convinced a reluctant Ertegun to invest in during the late 1950s. According to Dowd, Ertegun’s initial response to the request for $12,000 for the console was, “Twelve thousand dollars? That’s how much it cost to start the whole company!” Dowd had pointed out how amazing the Les Paul and Mary Ford records were sounding and how successful they were, and Ertegun finally agreed, though Dowd’s use of multitracking had mainly been limited to jazz records for artists such as the Modern Jazz Quartet and Ornette Coleman. Atlantic’s pop records continued to be done mainly on 2-track.

The 60th Street studio enabled Dowd to give the towering machine a permanent home, though he also had to scramble to build a new console for it, as well. The recording room was 37 feet deep, 45 feet wide and had a 15-foot ceiling, and would become home to hits including “Save the Last Dance for Me” and “Up on the Roof.”

That day in 1967, when Dowd came to the studio to meet Cream, he didn’t know until they showed up that their work visas were to expire the following Sunday, giving him all of three days to make the entire album. He was also not expecting to see a trio of roadies setting up massive stacks of Marshall amps and a double-bass drum kit. “I thought to myself, ‘Three guys need all of this?’” he recalls. “Then I find out that a limo is going to pick them up Sunday morning, and we have to be finished with the whole record by then.”

The band zipped through six or seven songs very quickly, including future classics “Strange Brew,” “Dance the Night Away,” “Tales of Brave Ulysses” and “SWLABR.” Dowd was impressed by their tightness, apparently honed during their first U.S. tour. “They came in and were very no-nonsense,” Dowd remembers. “They went through the first few songs like greased lightning.”

That wasn’t the case with “Sunshine of Your Love.” Clapton and Bruce had their parts down — basically the famous riff that plays throughout virtually the entire song that the two play in unison. Baker, however, was having trouble finding a groove for it. So the song was pushed toward the end of the sessions.

And the recording setup would be waiting for it — it remained the same for the entire record. Dowd used a pair of Neumann U47 microphones as overheads for Baker’s array of rack and floor toms and four cymbal trees, close-miking the hat and snare and kick drums only. The kicks got E-V RE20s, though Dowd would ask Baker on each song if he would be using double-kicks. The hat and snare had E-V 666 and 667 mics, respectively, which Dowd remembers fondly as having remote EQs placed in-line so he could adjust them from the control room. In addition, he placed a pair of condenser mics in an “X” pattern behind Baker’s seat, about eight feet high.

The massive Marshall stacks, guitar and bass had a single B&K ribbon microphone placed about two inches from one speaker and at a 45° angle, to deflect pressure and avoid stretching the ribbons. About two-and-a-half feet farther out, he placed a cardioid Western Electric 639A microphone on a stand aimed at the amps. “The volume was simply staggering,” Dowd says, still cringing at the sonic memory. “When they were playing, the room was up around 125, 130 dB. It was deafening. I would come out into the studio wearing headphones, and they thought I was listening through them, but I was just protecting my ears. But I couldn’t say anything. As far as they were concerned, I was a foreigner.”

The studio was large, but Dowd saw the futility of attempting isolation for any instrument, let alone vocals, which were mostly sung live with the basic tracks. “My big job was protecting Ginger from the double stacks,” he says. “They were 45 feet away, but no way could you isolate them meaningfully. It was pure bedlam.”

Drums were assigned to three tracks of the Ampex 8-track deck (running at 15 ips), the guitar was recorded in stereo, bass in mono, leaving three tracks for vocals and the occasional overdub.

Classic Tracks: Bob Seger’s “Night Moves”

“Sunshine” came into being after Dowd, still seeing Baker wrestling with the groove, suggested an American Indian-style tattoo beat. That did it. Baker was finally inspired, except that he put his own spin on it, playing the groove on the first and third beat of the bar, instead of two and four, as Dowd (and every confused guitar player ever since) had expected. Twenty-five years later, when they had all reassembled in Santa Monica, Calif., for a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremony, Dowd laughs that Clapton was still playfully chiding Baker for putting the groove on the “wrong” beats. As with the other tracks, Bruce sang lead into a Neumann U47, Clapton on harmonies on a U48. (Dowd says it might have been the other way around; his memory, though remarkably sharp, fails him there.) Those were keeper vocals, as well. And one of the vocal tracks became the home for Clapton’s solo, hidden there so the guitarist could keep the riff going underneath it on the basic track.

The guitar solo on “Sunshine of Your Love” is perhaps its most memorable moment: In the midst of a heavy rock track, Clapton breaks into an instrumental quote from the pop classic “Blue Moon.” Even Dowd was startled, though Clapton had apparently planned it that way all along. “I asked him why he was playing ‘Blue Moon’ as the guitar solo, and he says to me, ‘I want to show people that things in music haven’t changed,’” Dowd recalls.

The rest of Disraeli Gears went down similarly, and a pattern quickly developed: The band would play for three or four hours straight, then pile into the control room to listen to playbacks, determining, with Dowd, which takes were better and which needed redoing or punches. Then they’d take about an hour off, and then it was back to work. And so it went from Thursday morning through Sunday morning, when the limo driver pulled up just as they were listening to the final playbacks. “The reciprocity of working visas between the U.S. and the UK at the time was very begrudging,” says Dowd. “So there was no getting extensions. Whatever was done when the limo pulled up, that’s what would be Disraeli Gears.”

Dowd had been doing rough mixes as he went along, and used them as references when he started mixing in earnest on the following Monday. It was an easy mix, he says, not just because of the limited number of tracks but also because the band was simply razor-sharp. “There were no clams on those tracks,” he says. “Not a lot of processing, either; I’d say the room itself was 30 or 40 percent of the sound of that record, just because the band was so loud.”

And that’s why Dowd was stunned the next time he got to work with Clapton, on the “Layla” session, at Criteria Studios in Miami. Walking into the studio, Dowd was braced for another stack of Marshalls, perhaps even more of them than on the Cream sessions. Instead, he found Clapton playing quietly through a tiny Fender Champ amp. The contrast was startling, and as Dowd puts it, “If someone had walked into the studio that day during a take and their shoes squeaked, it would have blown the take.”