Manifold Recording co-owner Michael Tiemann, left, with studio designer Wes Lachot at the 1983 Yamaha C3 grand in the Music Room.

Projects like Manifold Recording don’t come around often in a studio designer’s life. A client with knowledge and passion for the way music works in a space and the way every bit of detail contributes to the whole. A proposal for a carbon-neutral, ground-up facility that starts with the sweet spot in the control room and the musician in the live room and develops from there. A request for drawings that include 24-foot ceilings and visual continuity from control room to music room to three iso booths and two sound locks, through windows onto the 16-acre property in the hills south of Chapel Hill, N.C. A budget that was comfortable—not unlimited, but better than most. It did, however, grow over five-and-a-half years while other projects started and finished. And studio designer Wes Lachot had no idea what he was getting into.

“When I got the call in February 2006, I had three or four other projects in development and told him that I was too busy, but if he called back in four to six months, I could sit down with him,” recalls Lachot. “I had no idea what this was about, and I almost blew it! But right at six months, he called back, told me what he had in mind, and it has turned into one of the most rewarding professional experiences of my career.”

Michael Tiemann, co-owner of Manifold Recording with his wife, Amy, laughs at the memory. “I went to Google and put in ‘Frank Lloyd Wright Recording Studio Chapel Hill,’ and Wes Lachot pops up out of nowhere. I looked at some of his designs and projects and could see that he had the kind of sensibilities I wanted to work with. I sent him an email and said I wanted to build a recording studio, and he said he was too busy! But I waited the six months, called him and convinced him that I was willing to go all the way to achieve an aesthetic and a creative vision.”

The creative vision Tiemann proposed was based around the musician and an environment where the Music Room would function as an extension of the instrument, be it solo or ensemble, voice or piano, guitars or drums. The aesthetic was very much influenced by Wright, based on an organic approach to architecture where you start with a seed, the sweet spot, and build out so that the building grows into the world around it, and every piece is part of the whole.

“It is certainly a luxury to not be constrained by walls at the outset,” Lachot says. “The physics of sound don’t do well with rectilinear geometry but behave more like a sphere. And we as designers are often forced to fit these round pegs into square holes, and it’s our job to take away some of the awkwardness. With Manifold, we were able to start with an equilateral triangle at the listening position, then work outward from there and develop this hexagonal type of geometry, meaning there are three axes of symmetry rathern than two [see floor plan diagram]. It has more in common with a beehive than the block you played with as a child. Everything else is an expression of that, down to the ways that the terraces flow into the land.”

CONCEPT TO REALITY

Michael Tiemann is a highly intelligent man, and this is no case of an outsider buying his way into the recording industry. He knows why he wants a flat response down to 25 Hz and is equally animated discussing the performance of the glass diffusors circling the control room wall as he is in explaining his personal conversion to an analog/digital hybrid model. In conversation, you get the sense that he is opening Act Two of his life, and in some manner he is returning from a detour in high-tech back home to his love of music.

As a 10-year-old in Manhattan, he appeared on his first record as part of the renowned St. Thomas Choir. Four more would follow. His mother was involved in professional music, as was his grandmother, and he was exposed to opera, symphonies, jazz and sometimes string quartets in the living room. His godfather, Russ Payne, was one of the engineers on a number of Miles Davis Columbia sessions of the late ’60s/early ’70s, and at some point drove home to young Michael the concept of layers in music and the magic of the recording/mixing/mastering process.

He wound up in the San Francisco Bay Area and was instrumental in the founding of the open-source software movement. It was an exciting time, he says humbly, and one gets the sense that by creating and selling a few companies, he was allowed the opportunity to pursue his original passion: the musical experience.

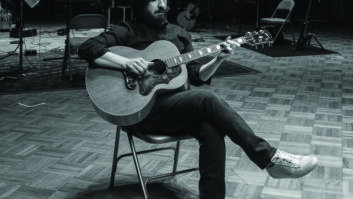

“While in Silicon Valley, I met up with this musician, Drew Youngs, who was at the time playing Latin jazz, who was incredibly talented,” he says. “I offered to fund his album and he recorded it, then brought it to Greenstreet Records, now Polarity Post in San Francisco. I was present for mixing and mastering, and it was an amazing process for me—to sit down and listen to how a record comes together. And it opened many more questions in my mind, including, ‘How is it that we can make an amazing-sounding record that the intended audience never really gets to hear?’”

A few years later, he bought the 17 acres outside of Chapel Hill, called Lachot and is now all set to open Manifold Recording this month.

BUILDING OUT THE REALITY

“The concept and the wiring and equipment and outboard and mic locker is very old-school analog,” Lachot says. “And it’s on a pretty large scale. But Michael was insistent from the beginning that the entire space was to be designed for musicians. So within the 24-foot-high music room, we were able to create these places of intimacy. We worked with Peter D’Antonio and incorporated an extensive amount of RPG acoustic products that in some cases bring areas of the rooms down and make it feel more human in scale.”

In the 21-inch-thick concrete walls, Lachot worked with RPG DiffusorBlox, which act as both diffusors and bass traps, having slotted Helmoltz resonators within them, tuned to different frequencies. RPG TopAkustik wood, highly absorptive, is used extensively throughout, in the side walls of the control room and in the cloud that fills the ceiling in the Music Room. The cloud is further defined by the RPG Bad Panels, a combo reflective-absorptive material. The reverb time is variable via reversible panels and sits roughly between 0.75 and 1.75 seconds.

The front wall of the control room incorporates an 11-foot broadband bass trap with a 4-foot air gap. Tiemann is particularly proud of calming the low end; he has an aversion to “glop.” Those colored-glass devices pictured on the cover are diffusors that change color depending on location and complement the Quadratic Residue Diffusor back wall. The room is modeled on the concepts of a Reflection-Free Zone. The entire structure was built, as all Lachot projects are, by Tony Brett of Brett Acoustics in Durham Hill, N.C.

Tiemann freely admits that the API console wasn’t part of his original plan—he was leaning toward digital—and he was convinced, in part, by Lachot to look at the Vision. “What API did, whether by accident or design, is they produced a topology, a circuitry and a quality that you can listen to, and say, ‘That is the sound,’” he says. “And if you look at the picture of the Vision in the control room, my gosh, it fits well.” [Laughs]

The Vision has 48 channels of 550L EQ and 16 channels of 560 L EQ, with two 12-slot penthouses above the patchbay to house current and future 500 Series modules. Sixty-four channels of Harrison analog I/O feed the faders, with an additional 48 channels of Harrison analog I/O integrated with the aux, cue and effects systems. Eighty more channels of digital I/O are available for video and additional effects systems.

Like the API Vision, which presents stereo and surround mixes as two different entities, the control room offers soffit-mounted Dynaudio M4s to provide stereo monitoring while surround monitoring is separate, with mid-fields or near-fields on telescoping Sound Anchor stands. The Annex is a 5.1 room, completely digital, based around a Harrison Trion console, with monitoring yet to be determined.

Chief engineer Ian Schreier selected much of the outboard gear, and the facility is stocked with D.W. Fearn, Manley, Tube-Tech, Millennia, Lavry and Avalon. The mic locker includes models form Neumann, AKG, DPA, Earthworks, Coles, Royer and Sennheiser, among others.

Tiemann is both a visionary and a realist, and is fully aware of the economics of today’s recording industry. He realizes that he will not make his investment back by booking time at an hourly rate. His dream is much bigger, and admittedly bolder, and it centers around the participation of the audience as a co-producer on any and all projects.

“For the past 20 years, I’ve felt that the music industry is headed in the wrong direction when it comes to recorded music,” he says. “Especially when you look at the loudness wars. Then in live music, with larger venues and moving the audience further away, you’re selling less and less music to more and more people. We’ve finally begun to see the limits of what people will tolerate. I believe the best remedy to this problem is to reboot the expectation of an artistic performance and go back to the fundamental of people sharing space in a room. There are a lot of people who want to participate and produce that kind of experience. Miles Davis used to bring 30 or 40 of his nearest and dearest and play to them in the studio. We find what it means to become a co-producer of the performance they witness; this will create an apostolic revolution. They will tell people they have again found meaning in music.

“To me, music is a story,” he concludes. “When you do not invite the audience to be producers, they do not engage in the story. We’re creating an environment where what we are recording is a story told to those present and then shared. We want to reconceptualize what a musical production is.”

Floor plan of Manifold Recording Main building and Annex