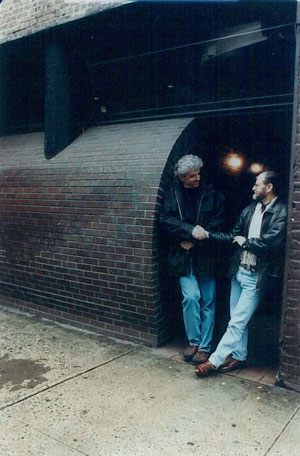

John Storyk and Eddie Kramer

When Jimi Hendrix and his manager, Michael Jeffries, decided to buy the recently closed Generation Club in Greenwich Village in mid-1968, the plan was to redesign the space from top to bottom and also have a small 8-track studio on the premises. A young architect named John Storyk was hired, and Jim Marron, who had worked over at one of Hendrix’s other favorite clubs, Steve Paul’s Scene, was to supervise the transformation.

Engineer Eddie Kramer, who had worked with Hendrix on all his albums, recalls, “I remember walking down the stairs and my first impression was, ‘Oh, my God, this is a fabulous space.’ I walked around and checked it out, looked at the square footage and finally I said, ‘Guys, you’re crazy. Why on earth do you want to build a nightclub? Why don’t we just build the best recording studio in the world?’ And they looked at me like I had four heads.

“Poor John Storyk had already drawn up all these plans for the nightclub, and he was furious; he was not a happy camper,” Kramer continues. “But soon he realized that this would be a great challenge for him, and this is what management and Jimi really wanted—a proper recording studio. I think the fact that John was not a studio architect was actually to his advantage, because he started with a clean slate and he had a lot of great ideas and such a wonderful take on design.

“Then we brought in an acoustician, Bob Hanson. We kind of knew what we wanted—Olympic [in London] was my grade-A reference point. It was never too live nor too dead, and that’s what I was trying to get at Electric Lady. We also did things like making half the floor covered with carpet and the other half not carpeted.” The original walls had white carpeting on them, both for their sound-dampening qualities and to better reflect the colors that a theatrical lighting grid splashed around the room.

The main studio room “was not huge,” Kramer says. “The ceiling drops to 13 feet at one end, and is 16 to17 feet at the other. But it sounded good and it was extremely comfortable, which was very important to Jimi. We wanted to make sure it had the vibe that Jimi wanted”—which explained the psychedelic mural by Vance Jost, the sensuous curves in the studio design, and the lighting.

Kramer’s experience recording Hendrix at the Record Plant in Manhattan influenced the choice of custom Datamix consoles for Electric Lady. “We were convinced by the guy who designed and built that [Record Plant] console that his new board was going to be unbelievable, and he showed us some modules, and it looked pretty cool,” Kramer says. Unfortunately, the console builder was in over his head and way behind schedule on making the two boards he promised (one each for studios A and B), and when the first one was delivered, “it was unbelievably badly made,” Kramer relates. Then, when word came down that the console maker was about to be shut down by the IRS for failure to pay taxes, Kramer says, “We cleaned the entire place out of every module, every piece of test gear, and took it to Electric Lady. We literally had to rebuild the console. It took us two or three months of heavy work to make that thing come back to spec, and in the meantime, they were building the studio B console in the back.

“When we finally finished the console, we had probably the first fully operational 24-track console: I believe it was 48-in and 24-out and there were 24 buses, graphic equalizers on each channel, six EMTs, a cool monitor section, and we also had quad pan pots with joysticks made by API, because we had API faders. The first machine we had was a 16-track—an Ampex MM1000—but it was wired for 24, so when the first 24-head stack came in, we converted it to 24. We also had loads of 4-tracks and 2-tracks.”

According to Kramer, “Jimi had to keep going on the road to make money to support the building of the studio. It took a year and close to a million dollars, but it was definitely worth it. By May 1970, it was pretty much ready to go and we started doing test sessions. Jimi came in and spent three or four intense months there recording some of the best music of his career.”

Alas, Hendrix died in England less than a month after Electric Lady’s August 25, 1970 grand-opening party, but by then Kramer had already been bringing outside clients down to the studio for a while, with fabulous results. The transition from “Jimi’s studio” to a strictly commercial enterprise was surprisingly smooth, if emotionally difficult.

More than four decades on, through changes in ownership and gear (and expansions), it remains “Jimi’s studio” in spirit. And to hear Kramer tell it, the original owner still turns up there on occasion: “If I’m working there, I know Jimi’s presence is behind me, tapping me on the shoulder, saying, ‘Hey, why did you do that?’” he says with a laugh.