Ricky Reed’s Elysian Park studio looks out over the rolling hills of L.A.’s Echo Park below, the tri-level facility’s 25×15 live room filled with natural sunlight streaming in from two large windows. A live plant wall acts as a natural diffuser, providing a perfect organic vibe for such analog goodies as Reed’s ’70s-era 32-channel Harrison 32C console, Arp 2600 modular synthesizer, Pioneer SR202 and Sansui RA500 spring reverbs, and a 1980s Pioneer consumer model 1/8-inch tape machine.

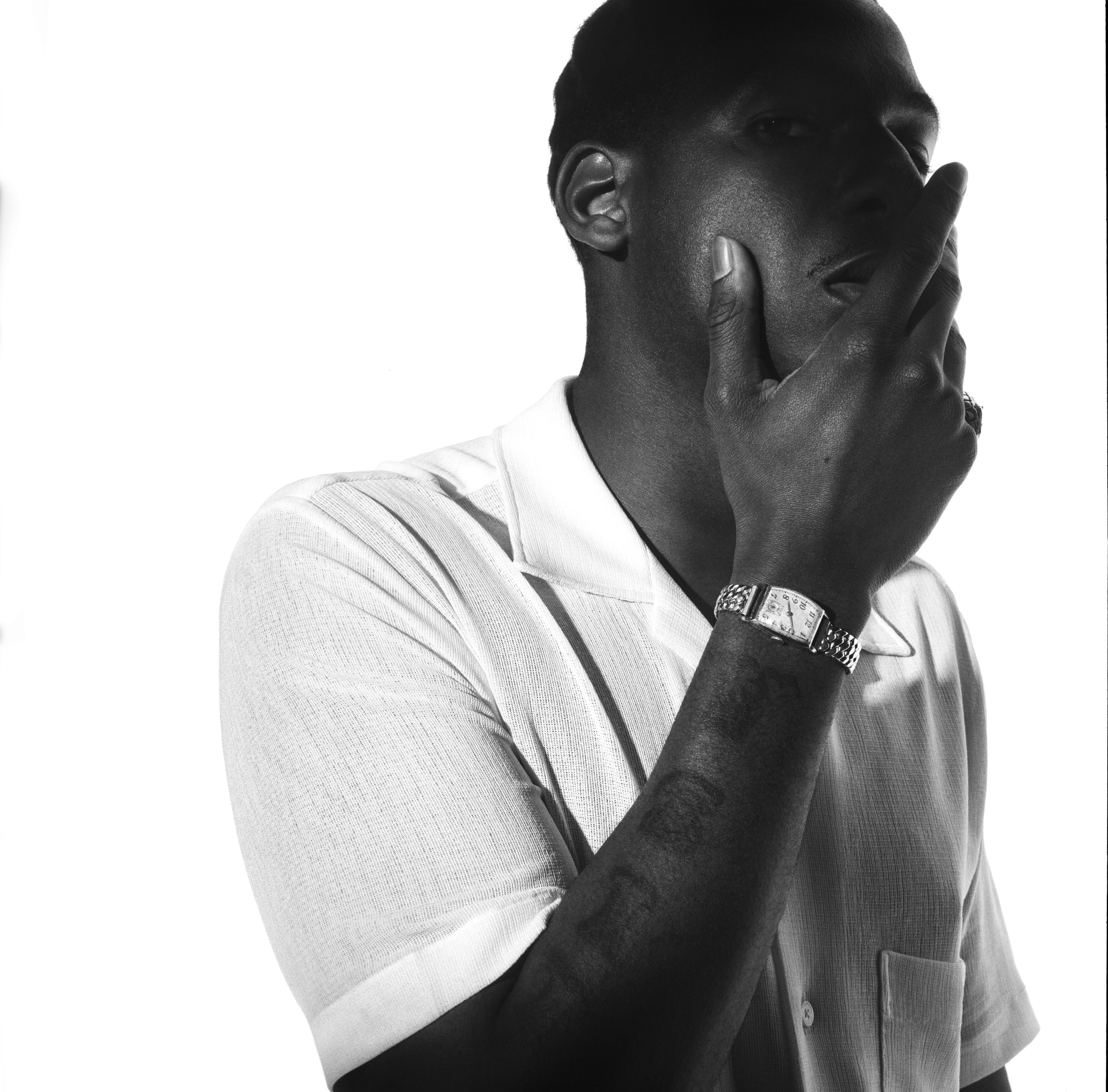

In this retro studio milieu, youthful soul singer Leon Bridges found a path to reinvention and regeneration, trusting Reed’s skills and Elysian Park’s old-school accouterments to create a thoroughly modern recording, Good Thing (Sony).

Produced by Reed (Kesha, Jason Derulo, Rhye, Halsey) and engineered by Ethan Shumaker with assistance from key songwriter/multi-instrumentalist Nate Mercereau, Good Thing capitalizes on the Texas-born singer’s extraordinary vocal and composing gifts. Reed and Elysian Park freed Bridges up, enabling experimentation while challenging him to move beyond the Sam Cooke comparisons engendered with his debut, Coming Home.

Leon Bridges, “Coming Home,” by Lily Moayeri, July 7, 2015

“I didn’t reach my peak with Coming Home,” Bridges says on the road from Chicago. “That sound didn’t define who I am. I had the confidence that I could make an album that you could place next to any major artist and it would be on the same level, and be true to who I am. I felt that Ricky was the guy to bring my sound to where I really wanted it.

“The whole session was me leaning over the console singing into a [Shure] SM7—we never used the multi-thousand dollar [Telefunken] U47,” the 28-year-old Bridges adds. “That was part of the beauty of it. Doing it that way really helped give the songs and the delivery an energy that you can’t get when you’re isolated in a booth. Honestly, I didn’t think the vocals I was putting down would be the final vocals, but we ended up keeping them. I didn’t know how it would sound, but I was open to trying new things. I would sing something and Ricky would play it back, and it sounded good so we kept it.”

A Workshop Approach

“The goal was to remove production and style from the conversation,” Reed notes. “We’d have Leon’s [basic compositions], then an instrumental backing started by myself or Nate or King Garbage from North Carolina. Then we’d find grooves that gave Leon a feel or an emotion and we’d write and record in real time, vibing on the different instrumental starters. Leon sat two feet from me singing into an SM7 as the songs were being written. And quite often that was the final vocal. His performances in the vocal booth didn’t feel as good as when he sat in the control room and we were chopping it up.

“Our U47 didn’t give us the same sound as when Leon grabbed the SM7 with the monitors blasting the music,” Reed, 33, adds. “The SM7 is darker than the U47. The SM7 is like some ribbon mics I own. It did well with the monitors playing in the room. From that we got performances like Leon’s never done before. Leon sang the words and emotions as he felt them in real time. When your voice sounds like that, you can put the focus on the performance and not nitpick the technical stuff.”

Good Thing was produced by Reed with executive producer Niles City Sound; mixed by Manny Marroquin at Larrabee Studios with mix engineer Chris Galland, assisted by Robin Florent and Scott Desmarais; and mastered by Chris Gehringer at Sterling Sound in New York City. Sessions began with Bridges’ song fragments, which were further developed by Reed and Nate Mercereau, as well as Austin Michael Jenkins and Joshua Block, all important players on Coming Home.

The Evolution of Frank Turner, by Anthony Savona, May 7, 2018

Created in workshop style, with Leon recording vocals as Reed and the core writing team of Mercereau, Wayne Hector, Michael Jenkins and Block crafted arrangements and structure, Good Thing is truly a spontaneous production. Lead singles “Bad Bad News” and “Bet Ain’t Worth the Hand” (both featuring songwriting contributions from Reed and Mercereau), position Bridges in modern R&B-meets-jazz and old-school soul situations, respectively, followed by minimalist R&B classic, “Shy,” country-tinged ’70s psychedelia groover “Beyond,” abstract love call “Forgive You,” Michael Jackson tribute “You Don’t Know” and bittersweet memory “Georgia to Texas.”

Tracking Good Thing

Reed brought Bridges’ new material to life with Elysian Park’s arsenal of vintage gear, including the original Steinway grand piano from Sound City, Slingerland drum set, Telefunken U87 and RCA 44DX microphones, Wurlitzer electric piano, VOX and Fender amplifiers, as well as Barefoot MM27 Generation 1 monitors, all around the Harrison console.

Bridges’ hand-holding the microphone in the control room gives Good Thing its intimate color, but it’s all business for the singer when tackling a take.

“Where I am in relation to the mic varies according to the vibe I feel for each song,” Leon explains. “There are times when I’d be pacing around the control room or I’d be hunched over the console singing or sitting on the couch. I definitely try to eat the mic when I sing. Everything is in the moment when getting a take. Sometimes we did multiple takes. The world I come from is a complete vocal performance top to bottom. I tried to do that this time, but it was nice to have the luxury to punch in to get the song where it needed to be.”

Engineer Shumaker manned the Harrison console, mic placement and routing. For that vocal, he says, “I always go into one of our two Neve 1070s and a Tube-Tech CL-1B compressor.

Larrabee Studios: The Best of Old-School/New-School, with Style, by Tom Kenny, Jan. 1, 2014

“Guitars are usually miked with a Shure SM57 and a Royer 121 through the Neve 1070s, often with a DI going, as well, through the Harrison 32C console,” he adds. “It’s the same model Bruce Swedien used on Thriller. We love it. This is a vintage board, so all 32 channels aren’t always fully functional. We keep it in working order.

“I generally point the 57 straight at center of the guitar cabinet cone,” he continues, “or at the seam of cone and main part of the speaker. Then the 121 right next to it. Depending on what’s needed, I will move them around a little bit. Maybe tilt the 121 slightly off-axis to warm it up. Then through the Neves.

“Keyboard is a Radial Pro DI to the Harrison preamps. For drums, a lot of 57s to keep it simple. An RCA 44DX on the kick drum. Another 57 on the snare drum and hi-hats, sometimes a Shure SM7. Toms are Royer 121s. Overheads are a pair of KM85is.”

Old Gear, New Sounds

Reed played an active role from songwriting to arrangements, and so did his instrument collection. A self-confessed “analog synth collector and pedal nerd,” Reed’s equipment closet includes such keyboards as Roland Jupiter 8 and D50, Arp 2600, Korg Poly and Juno 106, as well as a pair of atypical reverb machines.

“I’m a fan of old consumer home stereo reverbs,” Reed says. “We have the Pioneer SR202 and Sansui RA500, which came with record players. They allowed you to add reverb to your favorite LPs. These are analog spring reverbs. You can even chain them together and they sound beautiful—dark, warm, lush reverb that we usually use on vocals.

“And we have an ’80s-era consumer model 1/8-inch reel-to-reel tape machine,” Reed adds. “We use that for a vintage feel. While recording, we play with the reels to give the sound a little warble [as in the intro to “Shy”]. It makes a one-of-a-kind sound. I also use the built-in spring reverb from the Arp 2600. We might run vocals into the Arp for its spring and record the output from its speakers. That’s a treat.”

Nate Mercaneau is Good Thing’s secret weapon, the guitarist playing multiple instruments while contributing some of the album’s best material, including “Bad Bad News” and “Bet Ain’t Worth the Hand.” He also played the amazing Wes Montgomery–worthy guitar solo on “Bad Bad News” with a Roland GR-300 guitar synthesizer.

“Leon brought in raw, unfinished songs,” Mercaneau says. “We played with those ideas with Austin and Josh from his first record. Leon might come in with a chord progression or a melody and we’d build around that or find the best way to express his idea.

“I tracked some of the music at my place, layering instruments into a laptop and a 4-channel Focusrite Scarlett 18i8 interface,” he adds. “Shure 58 or 57 microphones. Guitar and bass direct, and for drums a combination of live and programmed elements using Ableton. ‘Bad Bad News’ is an Ableton kick drum, the rest are live drums. My go-tos include an old Fender Vibrolux amp, the Roland synth guitar and a ’70s Gibson 355.”

Where Coming Home branded Bridges as an old soul working a nostalgic style, Good Thing is a thoroughly modern interpretation of the classic soul of Otis Redding, Jerry Butler and, yes, Sam Cooke using modern production as its sonic bed and touchstone.

Sterling Sound, by Paul Verna, Dec. 1, 2002

“If you take my first album,” Bridges says, “that was at a time when I had never really sung in front of an audience. I didn’t have the pressure or expectations I have now. It was a different process and feeling. Some fans wanted me to make the same kind of album as before. But it’s not up to me to be a Sam Cooke prodigy. And this new album is not a full departure from that sound. I wanted to make an album to open a door, to be free to make anything.”