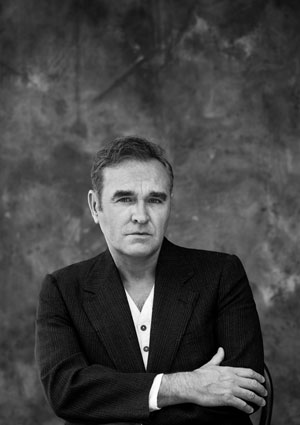

Photo: Greg Gorman

When producer Joe Chiccarelli describes the Morrissey album he produced last winter as “musical theater,” he doesn’t mean it in the Showboat way. It’s a record full of original stories, with dramatic productions that frame the iconic artist’s creations in theatrical settings.

Many of the 18 tracks begin with some kind of strange and powerful intro—some longer than others—and they’re more or less related to the overall sound and feel of the arrangement. The title track, for example, opens with low bass tones and world music-style drum beats and percussion. The beats carry on into the track, but the song soon breaks open into big, swelling guitar riffs and keyboards, and of course Morrissey’s magnificent, throaty, unmistakable voice.

Chiccarelli produced Morrissey and his touring band in the idyllic La Fabrique studio in St. Remy, a lovely town in southern France. “I was a little nervous, because when you transplant eight or nine guys to a foreign country with all their gear, sleeping in the same place, you don’t know if it will work out,” Chiccarelli says. “But this place is gorgeous, and the studio is world-class. They fell in love with the place, especially Morrissey. He even loved to go look at the frogs in the pond.”

Before heading to France, Chiccarelli had asked Morrissey to provide demos of the songs they’d be working on, but by the time they all arrived at La Fabrique, the producer understood that arrangements and lyrics would really come together in the studio.

Engineer Maxime Le Guil and producer Joe Chiccarelli in La Fabrique Studio.

“The funny thing is, I insisted on those demos, and he said, ‘Absolutely,’ and sent me 26 of them,” Chiccarelli recalls. “But there were no vocals. It was a surprise to me, but this is the way he always works. Sometimes the people he writes with put demos together, and then for the ones that inspire him, he’ll come up with melodies and lyrics to put on top. But you never ever know what that is until you go into the studio.

“The other unusual thing is, often he’ll do tricky things in terms of songwriting,” Chiccarelli continues. “If you go back and listen to Smiths songs or his solo records, you’ll see he will do things like sing what is the chorus melody—one time he’ll sing it over the chorus, but another time he may sing it over the bridge of the song or over a verse, and that transforms it into a whole new section. That means you can’t mess with his song structure much, because he’s treating it in a different way.”

Producer and band, and engineer Maxime Le Guil, developed a process of approaching the songs, nurturing keeper elements from the demos, while developing full arrangements: “First, Morrissey would sing two or three takes to the demo, or maybe with the band,” Chiccarelli explains. “These would be very raw—just an indication of where the song needed to go in terms of dynamics and rhythm—but often they would be strong and inspirational; it would all be there in those performances. At least half of the vocals on the album ended up being those guide vocals. We certainly re-sang a number of them, or improved on them, or comped between the guide vocal takes and new takes, but many of those raw vocals got used because they captured the spirit of the song.”

After laying down those guide takes, Morrissey would give Chiccarelli some guidance as far as where the band should take the song. “Sometimes it would be as simple as, ‘It needs to be big and grand,’ or, ‘This spot needs to be violent and ugly, but this spot needs to be more open,’” the producer explains. “Then he’d go away for a few hours while we worked on the arrangement and the parts, and when he came back after lunch, he would hear what we had and respond to it: ‘I love that, but this part needs to be more aggressive,’ or, ‘It’s too safe.’ He pushed me and the band in great ways.”

“Joe would then do another 10 to 15 takes with the band, focusing on specific sections of the song and working on the musicians’ parts,” Le Guil adds. “Then he would take about two hours to do a composite of the whole band between all the takes and make a rough mix for Morrissey to approve.”

On “World Peace Is None of Our Business,” for example, they started with a demo, but it didn’t have the world-beat intro or any of the detail that eventually added up to the majestic wall-of-sound opus the song became. “The entire changeup and feel from the sort of Phil Spector-ish verses to the T-Rex guitar solo—that all evolved in the recording, and Moz was great at directing how he wanted the intro pieces to be and the emotion and color of it. His sense of the big picture is fantastic, as is the band’s ability to interpret that sense—especially Matt [Walker], the drummer’s ability to take Moz’s thoughts and turn them into rhythms,” says Chiccarelli.

“I don’t think there’s anything on that particular track from the demo that remained in the final,” he recalls. “There are songs on the album like ‘Staircase’ and ‘Earth Is the Loneliest Planet’ where a couple of elements from the demos might have been retained in the final version, but for the most part, ‘World Peace’ was created from the ground up.”

Le Guil tracked everything—since anything might be a keeper—to Pro Tools (24/96, Lynx converters). The studio includes several recording spaces with varied acoustics, but most of the band tracks were captured in the main tracking room, called The Arcade, which Chiccarelli describes as “a unique plastered room full of bookcases. It’s live but not overly wet and ambient.” Morrissey’s vocals were mainly tracked in a drum iso room. Still, the natural tone of other spaces came in handy.

La Fabrique studio.

“The building is a 200-year-old mill, but the actual property goes back to Roman times,” Chiccarelli says. “There’s all this beautiful stone in one open area, where we recorded the big parade drum and percussion instruments [for “World Peace…”]. A lot of the intros and all the wild reverb you hear on the record is real, natural reverb. There’s a stone stairwell adjacent to the tracking room that’s three stories; some background vocals were done there, as well as tambourines, other crazy percussion.”

“There are lots of very different acoustic spaces, from dry to very live, and Joe took advantage of them,” Le Guil observes.

The control room features a Neve 88R conole and plenty of outboard gear, and the mic locker includes classic Neumanns and models from David Bock. Chiccarelli and Le Guil brought in some pieces, as well: Neve and API modules, and a Blue Bottle mic that became one of three go-to mics for Morrissey’s vocals.

“Some songs were to a new Telefunken USA U47, a lot of songs were to the Blue Bottle, and some were to an old Neumann U 47,” Chiccarelli says. “The preamp was always either a Neve 1073 or a Neve 1081; the limiter was a Tube-Tech CL1B, and then there was also a Tube-Tech EQ as well.

“The chain we used depended on what range he was singing in. Sometimes I’d need something a little thicker or warmer, in which case the older Neumann was a little chestier-sounding. When I needed something a little more exciting on the top end, the Telefunken delivered that. The Blue Bottle microphone was interesting in that it has a lot of presence to it, and it seems to project itself through the track in a really nice way. It’s a very forward-sounding microphone.

“As far as the reverb on the vocal, the interesting thing there was, at La Fabrique they had an EMT gold foil plate, an EMT 240, which was never one of my favorite reverbs, but somehow on Morrissey’s vocal it sounded perfect. There was something just bright and alive about it that worked well with his voice.”

On instrument tracks, Chiccarelli and Le Guil went the extra mile to set each track apart, to make it special within its own “theatrical” setting:

“Jesse [Tobias, guitarist] is especially great at coming up with unique guitar colors, so we used a lot of pedals, stompboxes, and mixed and matched things in a lot of weird ways with overly distorted sounds, as well as using the acoustic spaces,” Chiccarelli says.

Le Guil captured electric guitars with a Royer R-121 and Shure SM57 (phase-coincident) into vintage API 312 pre’s and bused into an API 550A EQ and UREI 1176 RevF compressor. “This is Joe’s trick to capturing guitars,” the engineer says. “It gives you a very rock, in-your-face sound, which he also got in the past on the Jack White records, for example. Yet it’s very respectful of the tone of the guitarist.”

“It’s interesting: I work a lot with studio musicians, and they’re used to making records all day long, whereas this band is a live touring band, and some of them don’t have a lot of studio experience,” Chiccarelli says. “The skill set that you use in the recording studio is different from live, but what these players brought to the project in terms of intensity and excitement, and that over-the-top dramatic quality to their playing, made them fantastic collaborators. They are his family. They are his band, and they understand him and understand what he wants. Some have been with him for years, some are relatively very new, but they were all really committed to him and to his vision.”

Chiccarelli mixed the record mainly back on his home turf, at Sunset Sound in L.A. “We started cleaning things up, but when Capitol let us know what our deadline was to meet the iTunes delivery date, I realized it was quite impossible,” Chiccarelli says. “So, the mixing got pretty crazy. I had four engineers in four studios going at the same time: Maxime in Paris, I was mixing at Sunset Sound and Ken Sluiter and Csaba Petocz mixing in rooms at The Capitol Tower.

“I was fortunate they were available. They are true professionals and there were no egos. I was lucky they worked long hours to get the job done and delivered great mixes. The last five days were pretty overwhelming for everybody especially Morrissey. It was pretty intense with files coming in from all over the globe at all hours. Then trying to get Morrissey and the label to approve mixes. Then uploading them to mastering in time, but we got it done.”

Contributing editor Barbara Schultz is also the managing editor of Electronic Musician and Keyboard magazines.