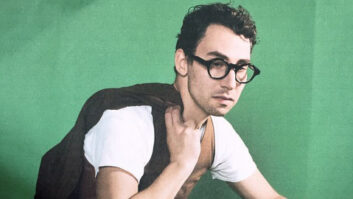

Allaire Studios manager Mark McKenna (seated) and chief technical engineer Ken McKim.

Photo: Wade Grindle

Keep the horse you rode in on, or switch to a new steed? For New York-area audio facilities where a mainframe analog or digital desk remains the center of operations, the decision to change consoles can be one of the most significant undertakings for management to consider. In a complex formula, potential gains in creative options and sonic quality must be balanced against downtime for the switch-over, unpredictable client preferences and the sheer expense of the flashy new investment, among other factors.

At Allaire Studios, the destination studio set high in the hills of Shokan, N.Y., deciding to switch out the SSL 9000J that had anchored their Great Hall studio was no sudden impulse. “When we purchased the SSL in 2000, our thought was that we would have a console that would be able to do a number of things well,” explains studio manager Mark McKenna. “We were anticipating 5.1 to take off and be a part of our daily operation, so we wanted to have a studio where people could not only mix in 5.1, but track in it. But the 5.1 market did not really blossom the way we thought it would.

“Also, we have this enormous tracking room, but in the final analysis the SSL is more of a mixing and urban tool, and it didn’t really fit the place,” he continues. “The other thing that pushed it over the edge is we had a remarkable run in our other studio, the Neve Room (featuring a Fred Hill-restored 8068). We had periods where the room was booked solid for six months with only Sundays off. We thought we needed to find a way to replicate that kind of performance.”

Through connections and good timing, McKenna and his crew realized that they had the opportunity to procure none other than the famed AIR Montserrat console, which holds a number of distinctions. One of only three such consoles built and the only one currently situated in the U.S., the board was overbuilt by Rupert Neve to meet the highest standards of Beatles producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick.

Although its roots are in the 8078 console, the 52 mic/lines in the AIR Montserrat board is distinguished by remote-controlled mic preamps, bandwidth approaching a whopping 100 kHz and a dynamic range of 106 dB. It also boasts 52 Flying Faders, a 32-input monitor section and six reverb returns for 90 total mix inputs. Just as remarkable as its technical pedigree is the history that has developed around it, recording such albums as Synchronicity and Ghost in the Machine by The Police, Brothers in Arms by Dire Straits and more AIR Montserrat projects from the likes of Paul McCartney, Stevie Wonder and Eric Clapton. After a 1987 relocation to A&M Studios in Los Angeles, U2, Aerosmith and the Rolling Stones are among those who took a turn with the desk.

Following a reorganization at A&M, the mighty console was warehoused for approximately five years before McKenna, who had personally used it on Don Henley’s 1989 album, The End of the Innocence, discovered that it was available. “When I was at one of the AES conventions,” McKenna recalls, “I got a chance to talk to Robin Porter, one of the chief design engineers on the console, and other alumni at AIR, and they all said the same thing, which was that this was the best-sounding console in the world and they reckoned that it still is. I remembered that everyone who sat down at this console was blown away by the sound of it. Everything sounded more natural through it, like it sounds in the room.”

Allaire nabbed the AIR Montserrat board and then turned it over to chief technical engineer Ken McKim for refurbishment. “We spent a lot of time doing the repairs offsite to minimize the turnaround time,” McKenna notes. “We replaced all the patchbays, recapped the console, recapped the power supplies, but the board was in remarkably good shape.

“Our first client on it was Branford Marsalis — he was thrilled with it and the console performed flawlessly on his session, so it was a pretty auspicious way to kick it off. Since then, we’ve actually been doing more mixing on the console than we thought we would, in addition to recording.”

Combined with the awe-inspiring Great Hall, the spacious John Storyk/George Augspurger-designed control room and 5.1 Augspurger custom monitoring, it’s fair to say that the console switch was worth it. “It’s a statement of what we consider quality to be,” McKenna says. “There certainly are convenient aspects of digital, but I’m not sure there’s something as satisfying as recording through a console like this.”

Back in the urban grit of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, a similar scene — albeit on a different scale — was played out at the indie rock haven Studio G (www.studiogbrooklyn.com). Although the engineering/production team of Tony Maimone and Joel Hamilton, plus assistant Marc Alan Goodman, were booked solid with their customized 26×16×4×2 (Quad-capable) Auditronics console, Hamilton began to feel last year that his long-beloved board had hit the proverbial wall.

“I loved the EQ and the mic pre’s on the Auditronics, but I didn’t love a lot of other things about it,” Hamilton says. “I was spending all my money attempting to turn it into something that it wasn’t, which is — a Neve. I always wanted to get my own Neve console, and when I wound up doing a session on a 5316, I fell in love with it.”

Hamilton’s personal board/love child was procured from and commissioned by Sonic Circus. It’s a Neve 5316 with 32 channels of 31114 of EQ/pre. An all-discrete 8-bus design, the desk gave Studio G the mechanics they had been craving with 24 channels of uptown 990 moving-fader automation. Paired with the studio’s outstanding mic collection, choice outboard selection and relaxed vibe, the Neve helps to sell the room even better in a competitive environment.

Hamilton cautions against putting too much stock in a console swap for impacting business, however. “I can’t tell you if someone looks at the Website, and says, ‘I have to record there. They’ve got a Neve!’” he says. “I think people are more savvy than that these days. It’s more about what we can deliver. This isn’t a public studio with outside engineers working here: People get the room with one of us. So we’re an important part of the equation.”

Both sonic and fiscal improvements have been notable post-switch, however. “Keeping the Auditronics would have been easier — it’s a great console — but the relative headache of the swap-out was worth it the minute we started working on this board,” Hamilton says. “It’s a hard thing to describe: the depth of the relationship of the kick drum to the bass, the air around it, the headroom, this vintage discrete gleam. We just felt like our jobs got more fun that day.”

Send “Metro” news to

[email protected].