Communication is an intrinsic part of being human. Sharing ideas, feelings, opinions—that’s vital for the well-being of social creatures. Imagine having a terrible day and not being able to vent, all of that frustration bottled up inside. It’s said that “misery loves company,” but what if a person had no way of communicating with anyone else?

Director Jerry Rothwell’s documentary film The Reason I Jump delves into the lives of six non-verbal autistic individuals, one of them Naoki Higashida, who wrote the book that inspired and informed Rothwell’s film. In his book, Higashida sheds light on his mental process—what it’s like to be neurodivergent, and more specifically, what it’s like to be nonverbal.

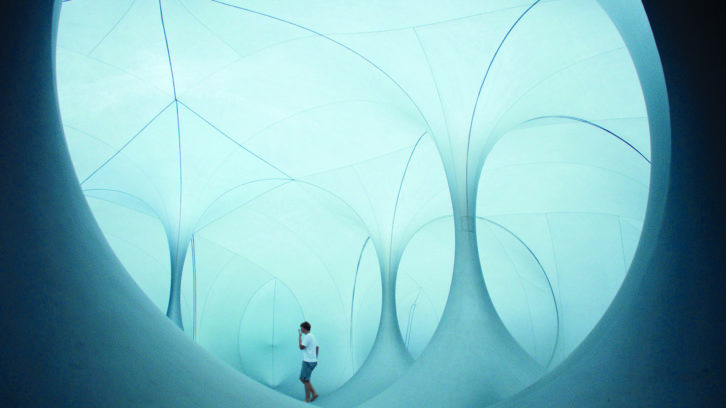

Because Higashida’s experience of reality differs from that of a neurotypical individual, Rothwell had license to play in a subjective reality as he interpreted the experience for the audience. Higashida wrote that in order to make sense of what’s happening at a particular moment, he scans his memory to find a similar experience. Rothwell represents this in the film using a rainstorm. The subjective sound of rain falling—played with processed chimes, glass tinkling and deep, reverberant droplets—is what transforms a typical rainstorm into something akin to Higashida’s experience of it.

The sound design—created by sound designer Nick Ryan—acts as an abstract representation of Higashida’s writings, while the music represents the emotional state. “Jerry [Rothwell] wanted to blur the lines between music and sound design, so they interwove hand-in-hand, illustrating and amplifying what the characters are feeling,” says award-winning composer Nainita Desai, who was named one of the Top 5 composers of 2020 by Britain’s Film4.

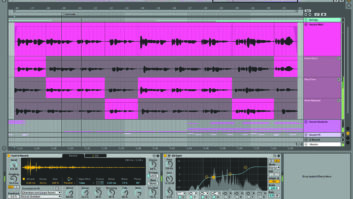

Rothwell asked Desai to work with found sounds in her score, and with her background in sound design and musique concrete, it proved a natural fit. “Sound design is very much a part of my foundation and what I love,” she attests, offering examples from the film that use close-up shots of fan blades spinning, a pottery wheel turning, and truck tires traveling down the road. “I took the location recordings they gave me, chopped them up and created rhythmical patterns out of them. Out of these found sound elements, I would grow and evolve pieces of music so that you didn’t know whether what you were hearing on-screen was music or whether it was tonal or whether it was sound design.”

In another scene, Higashida’s book lay open on a table. Desai used the subtle sounds of human breathing and water droplets hitting paper to create a rhythm track that precedes the visuals. “The effects and the music are blurred and jelling together,” she says. “It’s quite subconscious.”

In her score, Desai explored concepts that Higashida discussed as part of his perception of reality, such as repetitive and circular motion (time having no clear direction but just going around), and noticing small details first, which gradually coalesce into a complete image.

For Desai, the opening cue “encapsulates all the concepts of autism that we were trying to make people aware of in the film,” she says. “The first piece starts off with a lighthouse going round and round so you’ve got these oscillations, this circular motion. Just as autistic people perceive the detail in objects before they perceive the whole picture, I start with little fragments of tiny elements that come together like a jigsaw puzzle as the piece of music evolves, with string elements and saxophone and finally vocal elements over the title card. The elements appear in a very subtle way, introducing these characters to the world in a gentle way.”

VOCE PIENA

The film follows one autistic individual named Joss, who hears the hum of electrical boxes (or Green Boxes as they’re called in the film) from miles away. He’s drawn to these boxes, and loves the “music” he hears in the buzzing.

“To him, it sounds like a choir of angels,” Desai says. “We didn’t have the budget to record a choir, so our challenge was, ‘How can we do this? How can we go from the rumble of these generators and build it up to this massive abstract choral piece?’”

The solution was to record her own voice, one take after another, until she had nearly 50 tracks, as she explains: “I recorded in different spaces, with various mics, including the UAD Townsend Labs Sphere L22 to model various mics, the Neumann U87 and Neumann TLM193. I also changed my mic position to vary the perception. Sometimes I used my voice like a resonant cavity to change the character depending on the shape of my mouth. I recorded very long, single takes so that as the scene with the transmission towers opens out, the voices open out at the same time.”

Desai wanted the “Green Boxes” track to have full dynamic range, from low bass tenor to soprano, despite the limited range of her vocal performances. She says, “I used Logic and Melodyne’s pitch-shift processing for some of the layers to create a wider frequency range, and I’d change the formants as well with Soundtoys Little Alterboy. I enhanced the tracks with delays and reverbs like Exponential Audio reverbs, and Eventide Blackhole. 2CAudio’s plug-ins came in really handy, too.”

Music is used to convey a film’s emotion, but Desai also “wanted to represent the character’s internal voices with the human voice because they’re non-speaking,” she says. “But I wanted to do this in a more abstract, unusual way because of how they perceive the environment and the world around them.”

Desai’s vocals are a defining element that can be heard throughout the score. Through cutting, layering and processing she created complex, rhythmic, ethereal and evocative sounds. They’re sounds, not intelligible words. But the sounds weren’t arbitrary. She took key phrases from Higashida’s book (in their original Japanese) and broke them down into their smaller consonants, vowels and syllables.

“I deconstructed those broken-up phrases and then reconstructed them with various treatments and layering so I could create a rhythm using the voice,” she explains. “There was one phrase, for example, ‘we are outside the flow of time,’ which is a poignant phrase in the book. I wanted to get those aspects of autism across because the passing of time is very different from the way neurotypical people experience time.”

Desai experimented with granular synthesis using Output Portal, as well as GRM Tools, to add an “element of random chaos. I used unusual delays and reverbs to create a randomness to the takes and recordings where it would be slightly out of control. You didn’t know quite what to expect,” she says.

But Desai didn’t want the vocals to sound machine-like or robotic. Her treatments weren’t so extreme that the vocals ceased to sound human and organic. At the same time, the vocals couldn’t sound too intelligible, and she didn’t want them to be too pure or clean. “I wanted it to be slightly rough around the edges. I wanted to keep the rawness of the recordings and not clean it up too much.”

MAKING THE BAND

The found sounds and vocals are supported by cello, violin, prepared woodwind, and saxophone—sometimes treated until the source sound is unidentifiable. Instead of roughing out complete cues using virtual instruments and then transcribing those parts for the musicians, Desai chose to construct the score from a series of experimental sessions with cellists Elisabeth Wiklander (who is autistic), Marion Long and Matt Hawken, violinists Daniel Pioro and Sarah Harrison, bassist Malcom Laws, saxophonist Ben Vince, clarinetist Heather Roche, and guitarist Arthur Dick.

Her first rounds with the musicians were more aleatoric. Working with one musician at a time, Desai would prepare ideas and sketches for that musician as a creative kickoff for their improvisation. But she would set strict parameters for the improvisation initially, and then guide their performances using hand signals during the recording sessions.

For instance, while working with the cellist, Desai says, “I would direct the player to only use five notes and then conduct them by pointing my finger upwards when I wanted them to go up a tone. If I pointed my finger downwards, I wanted them to go down a tone at specific moments in time. I’d record that as a take. And then we’d do another layer on top and another layer and another layer. We’d end up with this interweaving sea of cello parts that created a really thick, rich piece of music that was based on pure inspiration. It was really quite exciting because there was this element of the unknown coming into the recording session.”

Desai worked with clarinetist Roche to create a prepared clarinet. They covered the bell of the instrument with aluminum foil and put some water into it. “It created this amazing sound, almost like a didgeridoo,” says Desai. “We thought, ‘How far can we push this?’ I was just trying to be more experimental and find ways of creating a library of sounds and phrases that I could play with and integrate into new compositions while I was writing.”

Desai wasn’t scoring to picture in these early sessions, so her imagination provided inspiration for how the score might sound. She would compose tracks and then bring the musicians back in to play on top of those. “Bringing in the musicians at various stages would take me off onto different creative tangents. It was like having a branch of a tree and then going off into lots of different branches as the months evolved,” she says.

This improvisational aspect continued through editing, as well. Desai would compose five or six different ideas and give those to the director and editor, who would edit the tracks into different sequences in the film, sometimes “totally out of context in places,” says Desai. “They would send me the rough-cut scenes, and I’d see a piece of music used in a place I didn’t originally write it for. But it was really interesting and it worked. So then I would develop those pieces and write more to picture at that point.”

This exchange allowed the music to help inform the narrative as it evolved in the edit, and that helped to inform the music and the sound design, too. Desai says, “The sound designer would give me elements that I’d integrate into the music, and I’d give him my stems and elements and he would then integrate that into the soundscape. It was very much an organic process.”

RE-MIX

The score continued to transform throughout the film’s final mix. One of the most challenging cues for Desai was during a sequence in which the fictional representation of Young Higashida is wandering through a forest. The narration at this point discusses the experiments that the Nazi’s performed on people with disabilities during World War II. There are gritty archival recordings with the voices of Nazi “scientists” proclaiming their opinion on neurodiverse individuals.

“It’s a very dark moment in the film, a very emotional scene,” says Desai. “I wrote quite a dramatic piece of music using layered cellos, and it was quite abrasive and hard with driving energy. The piece worked on its own, but when we played it against the archival recordings, it was too much—too overwhelming and very emotive.”

Since she brought numerous dry stereo stems of her tracks to the Dolby Atmos mix with re-recording mixer Ben Baird (who began pre-dubbing at Aquarium in London before finishing the mix at Point1Post in Elstree, UK), they had the flexibility to deconstruct the cues, place musical elements in the surround field, and re-process the stems to blend with the sound design. “For that particular forest cue, we really went to town in the mix. We rewrote the piece with the stems in the moment in the mix,” says Desai.

While filming The Reason I Jump, the production sound team captured impulse responses of the different locations. They were used during the mix to treat the sound design and the score. Desai says, “We put the cues into the space of the environment on-screen. So the cello was put inside the sound of the forest. There, it’s much more dreamlike, stripped-down and reverberant. It’s echoey, and it’s weaving and drifting in and out. Another example is the piano cue in the art gallery sequence. You hear the sound of the piano and it changes from one space to another. It all goes toward having this subliminal, subconscious effect on the audience. When you’re watching the film, you don’t quite realize it, but it’s all having an effect on you. It was that much more immersive.”

The Dolby Atmos surround field was also very effective at enhancing the audiences’ experience of the green boxes sequence with Joss. The electrical buzzing gradually blends with Desai’s choir, building in intensity as Young Higashida in the film runs toward a tract of transmission towers.

Desai explains: “We really opened it out, with height and width, and frequency range. Sometimes we had elements swirling around at just the odd moment. I created various stems and grouped the vocals together and placed them around the space. The sound gets bigger and bigger, wider and wider until you’re totally enveloped in this choir of angels. When the film showed in Dolby Atmos at Sundance last year, it was just so powerful and quite overwhelming and slightly disturbing, as well—it was quite abrasive to a point where you almost wanted to cover your ears, like Joss does in the film when sounds become overwhelming.”