Fact: What we hear in a dramatic film is not what was happening when the film was shot. The final soundtrack is a carefully crafted representation of reality.

But in a documentary, is the sound we hear as it was at the time the image was captured? No. There is far less control (or even no control) over a situation or location in a documentary film than on a typical Hollywood film. There is no blocking, no run-throughs. Events unfold and the production sound mixer must catch-as-catch-can with a strong focus on dialog, as ADR on a documentary is out of the question.

So how far into imagination can the sound on a documentary delve before it becomes fiction? How much creative license does a sound designer truly have on a documentary film? What are the guiding principles for accuracy versus interesting in a nonfiction format?

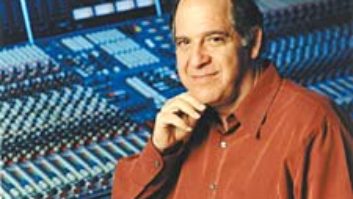

Sound designer/re-recording mixer Bernhard Zorzi—who worked out of Blautöne Studios in Vienna, Austria—crafted the soundtrack for director Richard Ladkani on his award-winning documentaries Sea of Shadows (2019) and The Ivory Game (2016). Both films are well-produced, visually and sonically captivating, with a compelling score and a dynamic, well-balanced mix. They are simultaneously entertaining and informative, blurring the line between dramatic and documentary film expectations, just as Ladkani intended.

“Richard wants to reach people who don’t usually watch documentaries,” Zorzi explains. “He wants to create a movement of change, especially through engaging young people, to inspire them to take action. He wants to give them the opportunity to be absorbed by the movie, and young people are used to experiencing rich visuals and sounds, so everything has to be vivid and interesting. He wants to motivate people to watch the film, to stay on it, while also delivering an interesting investigative narrative and a thrilling effect. I’m supporting that with sound while at the same time trying to be as authentic as possible and as accurate as possible.”

Authenticity in documentary sound is a task that requires significant mining of the production tracks; the effort yielded gold on these two docs because production sound mixer Roland Winkler “somehow always had the sounds we needed in his tracks,” says Zorzi. “Richard [Ladkani] would talk about or remember something that would be perfect, and 99 percent of the time I could find it in Roland’s tracks.”

Zorzi listened through every second of the location recordings, searching for necessary and useful elements, like elephant grunts and villagers yelling for The Ivory Game—pulling them from the background noise using spectral editing tools and EQ, and then layering and positioning them to create new ambient tracks to fill out the surround channels. “It is a manipulation of sound because it’s not a direct path from a microphone to the final soundtrack. But it’s the sound from those locations, which provides both authenticity and support for the story at the same time,” Zorzi explains.

For example, in Sea of Shadows—now playing in select theaters—a group of vigilante environmentalists called the Sea Shepherds (yes, those Sea Shepherds from Animal Planet’s Whale Wars) use drones to seek out poachers and destroy their nets, which harm all matter of sea life, including the nearly extinct Vaquita whale. During one nighttime expedition, the poachers shoot down the Sea Shepherds’ drone. According to Zorzi, the drone explosion sound was 80 percent production, with additional sound design to enhance the impact. “We wanted to get closer to the explosion, so we added some supporting layers and a low-frequency effect. That was it,” he affirms.

Zorzi also supported the scene by building layers of ambient sound to fill up the Dolby Atmos surround field, and used object panning into the front ceiling speaker to put the drone’s “explosion above the audience, to make it as immersive as possible,” he says.

Sometimes Zorzi had to manipulate the production sound in order to rebuild scenes and use sound to help the director tell the story more clearly. For example, in the beginning of The Ivory Game (now streaming on Netflix), Ladkani rides along with Elisifa Ngowi, the head of intelligence for a task force in Tanzania, whose mission is to stop the illegal killing of elephants and the selling of their ivory. They are on a nighttime sting operation to apprehend an infamous poacher named Shetani.

The scene is dark; the pace is fast. There is a lot of action happening around the main characters. “It’s this compressed chase sequence,” Zorzi explains. “I can help the scene by focusing on which sounds are coming from the center speaker and which sounds are coming from everywhere else. But it was all there in the production tracks. It was provided and not made up. I’m using the real sounds recorded from the actual location and reworking them into a new soundscape built for cinema.”

There’s another chaotic nighttime scene in The Ivory Game in which Craig Millar, head of security for Big Life Foundation in Kenya, arrives at a village where elephants are raiding crop fields. Millar and a few helpers are chasing the elephants away, using fireworks to scare the animals without hurting them.

The production sound was distorted, but still provided a valuable framework for the action—as did Ladkani’s description of the situation. These guided Zorzi’s search for very specific sounds he needed to isolate in the production track. In some cases these sounds couldn’t be re-created—like the villagers yelling and the rushing, rustling sound of the dry grass they were running through. “This grass had a distinct, dry texture that we didn’t even try to remake on a Foley stage,” he says. “We wanted to use that grass from production. It was a big task.”

Other key sounds, like the elephants trumpeting in the distance, Zorzi mined from different location recordings captured for the film.

In Sea of Shadows, Zorzi reconstructed the sound of a riot, in which fishermen clashed with the Mexican police. Ladkani, who was caught in the middle of it, recounted details happening off-screen, such as cars crashing into each other in an attempt to flee the scene, rioters throwing rocks and the police firing guns into the air. The fishermen’s warning siren was blaring in the background, encouraging the assault.

Zorzi says, “We used the original recording to give us the timing and then supported that with other sounds, like rock impacts, to give it more direction and depth. Everything you hear was location sound, but there were enhancements necessary to spread the sound into the 7.0 ambiences we created for the Atmos mix. The siren you hear is something the fisherman used to alert other fishermen that the police were there. In this case, they used it as an attack siren.”

Despite Zorzi’s commitment to using actual sounds from the locations, he does sometimes have to fabricate elements for scenes with no sound. In The Ivory Game, there’s a scene in which a herd of elephants interacts with an elephant skull as Millar explains the family connections that elephants have. Foley played an important role in creating the elephants’ soft foot thuds and gentle kicks at the dusty ground. Their sniffing and quiet growls came from Winkler’s other production recordings on the film. But the sound of the elephant’s foot pawing at the skull was an element that Zorzi pulled from a sound library. “It’s an important moment that needed the right sound. I started with something very strange to go there that wasn’t related to bones in any way, but it worked perfectly,” he says.

“In sound design, what fascinates me is that you can find something totally out of context, something random, that has the right sound and works perfectly when put against picture. The sound I found really sounded like the elephant touching the skull with its feet. It conveyed the right feeling,” shares Zorzi. “It’s quite helpful to not define your limits rationally too much because so much happens out of intuition and experimenting and being open to trying different combinations of experimental and naturalistic sounds. That’s very important.”

Another scene that required realistic design was in Sea of Shadows when the Sea Shepherds are pulling the poachers’ nets from the water and cutting the marine animals free. “We wanted to be in the perspective of an animal being caught in the net, with the very uncomfortable sounds of stretching and squeaking and pulling. That, in combination with what’s happening onboard, creates a nice fusion of horrifying and hopeful. It was tricky to find this combination of sound, pulled from production and created in Foley,” says Zorzi.

In addition to sound design, Zorzi can help influence the viewers’ experience by guiding their focus via the mix. For example, in Sea of Shadows a team of conservationists attempt to rescue a Vaquita whale and raise it in captivity. The corralled animal panics, forcing the team to release it back into the open ocean.

Zorzi and re-recording mixer Michael Plöderl started the scene with naturalistic sound coming from the entire Atmos surround field. As the situation intensifies, they slowly pull everything to the front until eventually it’s just sound out of the center speaker.

“We reduced and reduced and reduced, getting closer to the scene in which the marine veterinarian says, ‘That’s it. She’s gone.’ Then we have a shot where they’re lying on the boat and everything is silent,” Zorzi explains. “There is just the boat creaking that’s only coming from the center channel. It was an easy way to pull the focus in so that the audience is solely focused on the death of the Vaquita and the desperation of the situation.”

While documentaries are essentially nonfiction and deliver a truthful message, they still require a degree of manipulation in order to tell a clear story that resonates with an audience. With directors like Ladkani at the helm, those messages are delivered with style, delicately balancing the entertaining and informative aspects, as evidenced by Sea of Shadows’ success at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. It won the Audience Award for World Cinema–Documentary and was also nominated for the Grand Jury Prize in that category.

“The audience was drawn in and absorbed by the story, by the visuals and sound,” Zorzi concludes. “They liked it. Richard was so happy about that because that’s exactly what he wants to do; he wants to reach out to people, especially young people who can change the world.”