“The difference in being an artist/producer and being just a producer is that I’m involved in the whole gamut of things from the song’s birth to its completion,” says Narada Michael Walden, “and it gives me a real strong love for the material.” Even at the relatively tender age of 30, the drummer/keyboardist/singer/producer speaks with seasoned insight about the advantages, difficulties and rewards of filling the roles of both musician and producer in the pop music industry.

As we spoke in Studio A of The Automatt in San Francisco, Walden was finishing work on a new album by soul/funk singer Carl Carlton and he used the project at hand as an example of thoroughly involved he can become in the entire creative process. “First of all,” Walden explains, “I write songs. Then I bring the person into the studio with the band and I’m playing the drums. I’m showing what chords I want and what voicings I want on the keyboards. Then I teach it to Carl and actually track a song. I listen to it and make sure the sounds are correct—maybe I want a little more high end on the snare drum or a little more bottom on the bass—just check out the overall sounds and if it’s not quite right, we’ll go back and cut it again two or three times. After I have the exact time I want, then I’ll work on the vocals.”

But far more interesting than his descriptions of his physical immersion in the genesis of recording are Walden’s carefully considered and gently spoken observations on the delicate relationships between artist and producer. As a drummer, Walden was first head on record in the early 1970s on the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Apocalypse, Visions of the Emerald Beyond and Inner Worlds. By 1981, the young man from Kalamazoo, Mich., had performed on nearly 40 record dates and had produced a dozen albums by such artists as Sister Sledge, jazz trumpeter Don Cherry, Stacy Lattisaw and Angela Bofill. With the release of Confidence (Atlantic) in 1982, Walden had also recorded six albums under his own name aimed at the commercial R&B market.

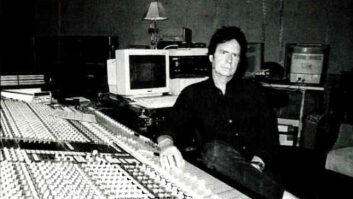

Programmer Bob Smith, percussionist Greg Gonaway and Narada Michael Walden work out rhythm tracks at Tarpan Studios, formerly Tres Virgos, in 1987. Note ancient E-mu SP12.

Photo: George Petersen

When he first worked with guitarist Mahavishnu John McLaughlin, Walden not only found a guru in Sri Chinmoy (who gave Walden the name Narada), but he studied the production techniques of Sir George Martin. Later, when he cut his debut solo album, he was looking over the shoulder of Tom Dowd. “I was always keeping my eyes open, my ears open to what we were doing,” Walden recalls. “Why we were doing what we were doing and what they were looking for in a take.”

He was eager to produce himself but had yet to prove himself to his record company. “I know when I was forced to use producers,” Walden says, “I couldn’t find anybody I wanted to work with. People who I wanted told me, ‘Okay, two years from now we can work with you but right now we’re tied up.’ It really slapped me in the face how desperately needed producers are.”

And he learned how sensitive and tender a producer needs to be with a performer. “I think what an artist comes to a producer for in the first place is love and care,” Narada muses, “and to make it easier to get a big record. An artist is insecure. An artist wants to feel that there’s someone there to help him. When you’re out there by that microphone, you’re exposed to the whole world. I have found in my life that I have a talent to make people feel comfortable when it comes to exposing themselves in that way.

“Every producer/artist relationship is different,” Walden continues. “Some artists need you to do very little. Other artists need you to do almost everything but sing and I enjoy that. I’ve never really tried just doing very little” As most of Walden’s artists are singers, he views the individual song as the determinant of success or failure. “I think music is among the last enterprises left where you can go from rags to riches overnight, if the song is there,” Walden explains. “One of the hardest things in what I’m doing, whether with Carl Carlton or Angela Bofill or Stacy Lattisaw or even myself, is either finding the right song or having the capacity to write the right song. So many albums do not do well because the right song was not there.

“That’s where most of my energy goes,” Walden elaborates, “into just finding the right direction for the artist. Where do you want to take them? And what is the song? Is it the right song for this person? Everybody has to have their own niche, their own sound, or else everyone ends up sounding alike and you’re down the tubes. But once I’ve got the song that I know I want to do, it’s a piece of cake just to make it shine and cut the right track for it. That’s the easy part.”

Even while he strives to create an individual sound for each artist, Walden does have certain preferences. He has worked at the Power Station and Atlantic Studios in New York and Trident Studios in London, but he makes The Automatt his home base both because it is not far from his Marin County residence and because he loves the “very clear powerful sound” of the big Trident console there. And he likes all of his records to have a certain feel. “One thing that I really love,” Walden explains, “is a huge wall of sound. I love echo. As I was growing up, I was very impressed with Phil Spector and his sound. And I’ve ever since been impressed with that bigger than life sound. I like it when my record comes on the radio and no matter what I’m doing it just takes over.”

Not surprisingly, the essence of that overwhelming sound for Walden is drums. “I really feel that being a drummer, I have an advantage in making records,” he explains, “because you can have an adequate bass player, an adequate guitar player, but, I’m telling you, if the drums are not happening, if the drums are not locked, it’s like the heart of the music is gone. If the drums are not spectacular sounding, the record’s just mediocre. If you have really great drums, then everything around it can be just okay and it’ll still sound like a great record.”

Can he play and produce “great” drums simultaneously? “A hard part about producing and cutting at the same time is being able to know if the part you’re playing is really correct. When you’re on that side,” he says, pointing across the board to the studio, “it’s rough to know if this little ‘daka doo doo sshhh’ is as good as just ‘dat, dat-dat bum.’ But I’ve learned how to develop that. I really listen to myself more, have my earphones adjusted so I can hear everything crystal-clear and I pretend that I’m inside of them as I’m playing. I try to be in a detached state of mind as I’m recording so I’m not involved with, ‘Well, my ego wants to do all this but it’s not really right for the record.’

“Producing my own records is the hardest thing I have to do,” Walden admits, “because it’s very difficult to be detached and to really judge your own vocals. When it comes to vocals, that’s when you really need an objective view. So when I go to sing, I have to have an engineer with me who I know is very acute when it comes to flat and sharp to the minutest degree.”

Unlike his performing group, Warriors, which is more in the Mahavishnu vein, Walden’s solo records fall into the contemporary funk/R&B groove. And similarly, he says, “It’s a certain type of artist that will approach me at this point but I feel like I’m not limited at all. I’m just making my name getting hits doing what I’m doing—the Angela Bofill’s and Stacy Lattisaw’s—getting these people out to where they’re recognized, then all of a sudden, I become a little more valuable where I could more easily do the Barbra Streisand’s and Kenny Loggins’.”

Does he feel limited by the tighter black/white formats that have taken hold in radio with the trend toward more conservative audience-targeted playlists? “I feel like it’s just a state of things. But if you do a Carl Carlton, say, it’s automatic that you know that for him to even get played on crossover white radio, he’s first of all got to have a Top 10 black hit. So you’ve first got to get him up there on those black charts. It’s my job as a producer to be that guideline to the artist and to the company and to myself, in a way. If I know that I’m being paid to come in and give this person a hit, then that’s what I must do. Now if it’s agreed upon on the beginning that we don’t care about hits, that we want to make an artistic statement, that’s another ballgame.”

But Walden does not approach his task with the cynicism of a boardroom chart-watcher. His integrity as an artist and his unselfish nature shape his concern for the talents he transfers to vinyl. “I feel a great mission to taking on undeveloped talent or people who are great but have not had the chance to go to the Grammys,” he says, “a mission in my life to serve up-and-coming artists who are so talented and not exposed to everyone. I feel like if I have any talent at all in this business, it’s to serve others.”