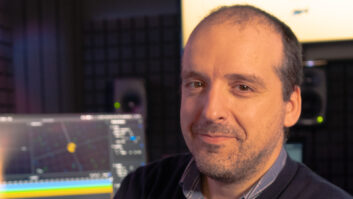

Full Compass founder and CEO Jonathan Lipp with the 1975 vintage

Clone Tone console he built for a local TV station.

By Frank Wells.

A museum of audio history that is part of the lobby at Full Compass’ new headquarters (see separate story) served as a springboard for a conversation with founder Jonathan Lipp, reminiscing first about the Madison recording facility that housed a home-built 8-track recorder and hosted such artists as Ben Sidran and guest engineers, including a young Bruce Botnick. Full Compass began as an offshoot of the studio in 1977. The studio was closed in 1980.

“I was a recording engineer, but starving,” Lipp recalls. “I always had fascination with being a merchant, but I didn’t have any experience being a merchant. I figured maybe I could get into manufacturing, maybe I could start selling stuff. Our focus was broadcast; it was the only national market for sound equipment in those days. And I was building things back then. I built this console [as he shows us part of the museum’s equipment inventory—a console, advanced for its time, that included digital meters and a stopwatch among its features] in 1975; this was for the local NBC affiliate. [I] built all the circuitry; it was in service for over 20 years.”

Though the company moved away from manufacturing, “we’re getting back into manufacturing now with Buzz’s group,” says Lipp, referring to the co-located and co-owned but independent FDW-Worldwide distribution company. Full Compass and Lipp also owned the “Clone Tone” brand, some of those products being on display alongside historic devices like Edison cylinders; the devices are all “part of the history of not only the technology, but the way it affected the performance of music” in those days, and composing.

“The original [Edison] cylinder machine” only recorded two minutes, later four minutes. “People didn’t normally record songs less than four minutes. It changed the way people performed and composed—if you were going to write something, it had to fit into the medium. The medium actually drove the art, and when the 78 became popular, and replaced the cylinder, it was also designed to give you approximately four minutes of time, and then the 45 rpm record replaced the 78, and was also four minutes, and so, the idea of a single composition being under four minutes, typically three minutes something, was the norm.”

AM and FM radio programming also adapted to the limitations of the media, says Lipp. “In the Seventies, FM radio changed from elevator music, because nobody was listening, and they started playing albums. And, of course, the Beatles did this radical thing and came out with a six minute song,“Hey Jude”—they could get away with it—[but] they had to cut it a little softer to actually fit it on a 45”

Lipp says Bruce Botnick explained to him why there were two versions of the Doors “Light My Fire:” “There was one on the album which was quite long and there was the edit for the air which was much, much shorter. I was amazed watching this man edit. He had pieces of a session wrapped around his neck and he could keep track of it, and he would do window edits where he’d cut a hole in the tape, long before there was automation…I even saw an edit that was a zig-zag because on one take, the guitarist held the note longer, and he didn’t want to cut off the guitar.” Lipp notes that while “this stuff is easy with digital editing,” it showed remarkable skill in those times. “Amazing,” he declares. “It was wonderful to watch him work.”

Lipp says historical perspective allows us, “to understand the full extent of how this has affected the industry and the way we perceive music, [that music] is often technology-limited because technology’s changing. The art hasn’t followed yet, but it certainly will. The old lines of distribution [are changing]; with the record companies, nobody wants to lose the business that they have, obviously, but the world changes, the industry changes, the market is much more flat. The chances of an independent artist [having success has] already changed dramatically, as have people’s expectations as far as what they want to be able to do. There’s a lot of debate about whether things like Guitar Hero and these other programs are good for the music industry, [for] the recording industry, because you don’t really have to be a musician. Of course, I hope that people love it enough that they are going to want to be musicians. I don’t know anybody who plays guitar who thought it was going to be easy to learn, and they can’t believe they had to struggle through it, but they get great pleasure from it (and it doesn’t matter what the instrument is)…hopefully [these games] inspire a lot of people to want to follow that.

My Nashville base prompted Lipp to discuss music making from Music City’s perspective: “I’ve been telling people that go to Nashville, that they have to go the Country Museum [The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum], and they have to take the optional tour to studio B , the old RCA studio B. The tour is not oriented towards people who are in the recording or music business– it’s oriented towards people who are curious, to the general public. RCA had a habit of never ever getting rid of their equipment, so the old stuff is still there. There is this multitrack console there that RCA built by hand; there were only four of them that were ever built, as far as I know. New York, Chicago and Los Angeles had the big, two-story full-orchestra scoring stages, and they were always paired with an MM1000 16-track machine in the early Seventies, and the only one that was not in a big studio was in Nashville, I believe, and it’s sitting there with the MM1000 next to it. They don’t explain it [on the tour], that this was bleeding-edge technology. When you see how small the studio is and how crude the acoustics are, the ceiling acoustic tiles on the wall, and you know the great things that came out of that studio, it tells you that technology is never the limitation.

“Even back in 1971 when I was learning to be a recording engineer, it was very clear to me that, although we all loved the technology, the technology should never get in the way of art. Too many takes with an artist, while you are trying to get it right in the control room–by the time you get it right, the music isn’t right in the control room anymore. You can spoil the moment, and although it sounds counter to my business of selling gear, in my mind, a $20, old-fashioned, handheld cassette deck, recording a great performance sitting in front of a band, is infinitely more listenable than a bad performance [recorded] using the best equipment.

”The obsession with isolation has been with us since the Seventies really, again, often kills art. You have very experienced studio musicians who make something sound real and live, in the most harsh, isolated environments in the world. But there’s an electricity when a band is playing as a band together–and again, I would personally rather go for some bleed and capture an electric performance, than [for] total isolation and total control. It’s human nature; we want to be in control, but being in control is not necessarily all it’s cracked up to be.”

Full Compass

www.fullcompass.com