New York, NY (December 12, 2023)—There has never been a better time to be in the music business. Economist Will Page, formerly with Spotify, analyzes the numbers annually and recently reported that in 2022 music copyright was worth $41.5 billion—a 14 percent jump from 2021’s $36.4 billion, and a new record.

Not surprisingly, it’s the vast number of legacy recordings, the millions of tapes securely locked away in the archives, that account for a nice chunk of the business. There’s gold in them thar reels, and record labels and catalog investors are mining them for all they are worth, monetizing their assets through sync licensing for film, TV and commercials, reissues and compilations, merchandising, and other outlets.

The problem is, there are so many millions of tapes in the vaults that laying hands on the exact track in a timely manner can be like finding the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Archiving specialist Iron Mountain Entertainment Services stores many millions of music recordings in every imaginable format in its secure, climate-controlled vaults on behalf of big media companies and artists. But here’s the challenge: When a rights holder delivers any quantity of assets to IMES, those materials are methodically logged in and put on the shelves so that they can be readily retrieved when requested.

However, each individual tape box in that collection may be listed in the rights holder’s database with only limited information, such as artist name and song or album title, or some identifying number. How does anyone work out which box holds the released master from among the many multitracks, two-tracks, duplicates, outtakes and so on, all cataloged under the same song title? Often, the only way to find the right track is to pull every item off the shelves that meets the search criteria and read every label on every box. Whether that information is correct, or that the box holds the correct item, is, of course, another issue.

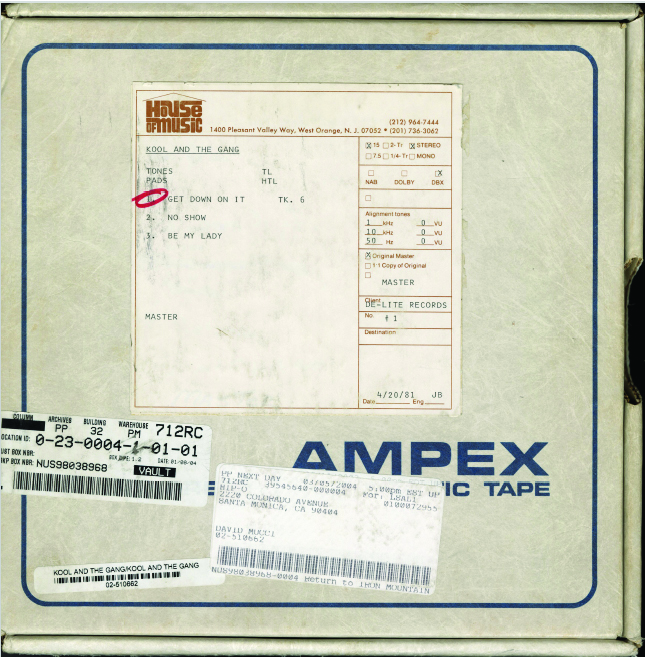

Metadata—the information that describes any given resource; in this case, what’s printed or written on, or affixed to the tape box—is key to finding a desired item. In the record industry, that has proven to be a slight problem, as historically, due to a lack of resources, time and will in the face of an overwhelming, growing number of assets, that metadata has only been comprehensively recorded and made systematically searchable for a small fraction of recordings. Creating detailed metadata is one of the core services IMES provides to the entertainment industry, and it has always been a highly manual and time-consuming task.

CHASING THE METADATA

As labels research archives for their next new project, sometimes they get lucky and find a hidden gem, but that’s no way to run a business. Robert Koszela, IMES Director of North American Studio Operations, recalls a conversation he had with Patrick Kraus, Universal Music Group SVP, Recording Studios and Archives. “Pat said, ‘We can’t keep finding stuff by accident. That’s not a business model. We need to be able to tell the powers that be what we have, where it is, what condition it’s in and be able to quickly retrieve it,’” says Koszela, himself a former UMG employee who worked as an engineer at Interscope Records under Jimmy Iovine.

Kraus’ original request was for IMES to go through prioritized sections of UMG’s archive, identify every item, and capture everything on the asset boxes. It was Kraus who challenged IMES to address the time-consuming, labor-intensive task of metadata collection from the label group’s archived assets, Koszela recalls. “Because they acquire so much stuff every year, it’s impossible to keep up with metadata collection in real time. The assets are meticulously organized on shelves with barcodes, but without comprehensive metadata, they can’t be fully identified or searched, and the manual process of metadata collection is extremely time- and labor-intensive.”

Metadata is expensive to collect because it has typically been done manually, and there are many and varied challenges. How, for instance, does someone populating an Excel spreadsheet for the label’s database notate something that has been highlighted with a yellow marker, circled with a Sharpie, or marked with an asterisk or checkmark? “It seems like the simple solution would be to just take pictures of everything,” Koszela says, “but there are challenges with that approach, as well, including image consistency, file naming, workflow, cropping, focus, lighting, et cetera.”

Saving Legacy Music Media? First Step: Remediation

In addition, photographing all six sides of a single tape box manually can take quite a few minutes. Alternatively, each side could be captured on a flatbed scanner, a method that IMES used previously, which can take eight to 10 minutes per box. On the scale that UMG was initially considering, about 2 million items, well, do the math. The process was going to take forever.

Furthermore, for a label, there may not be a budget to move an archived collection to another location, scan and log every item, and then decide where each asset goes—to the vault, to be digitized or even to be trashed. Whether manual entry or automated scanning, it was still a daunting, time-consuming task. One day, Koszela recalls, “Pat said, ‘Can’t you just bring the scanners into the vault?’”

AUTOMATED IMAGE ARCHIVING

At about the same time, IMES Engineering Manager Steve Hollencamp directed Koszela to a video of Smithsonian Institution archivists demonstrating their automated process for scanning a massive collection of ancient coins, which took only a few months to complete. Before long, Koszela was talking to a developer about building something similar for IMES.

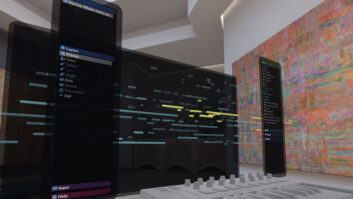

The wish list included the capability to photograph all six sides of a box and make any form of writing, from a penciled note to the small print on the tape manufacturer’s label, readable and therefore searchable—“And it all had to happen in under two minutes; ideally, under one minute,” Koszela says. Within a few weeks, the developer had checked off every box, had added photogrammetry, using lasers to notate the dimensions, and reported to Koszela that the machine could do it all in under 10 seconds. It was dubbed AMICS, for Automated Media Image Capture System.

About the size of an old-fashioned jukebox, the proprietary AMICS machine is the result of a collaboration between the company and UMG, in partnership with a third-party software developer and hardware manufacturer. Three machines are in operation, with a fourth on order.

AMICS has a glass panel on its work surface, lit from all sides, on which the asset is placed. The panel is accessible from opposite sides of the machine, so two operators can tag-team to speed things up. At the press of a button, six DSLR cameras simultaneously photograph the box, saving the images in a standardized sequence: front, back, primary and secondary spine, and top and bottom edge. The images are automatically cropped and virtually stitched together in the software, enabling a researcher to spin the box image onscreen, through 360 degrees on any axis, and check for any non-searchable annotations that might offer clues to the contents.

Using Google’s OCR (optical character recognition) cloud service, any print or handwriting is digitized and, with the requisite programming, will autofill searchable fields in the rights-holder’s database. Because the box dimensions are also recorded, any search can be refined to show only two-inch multitrack, or Sony PCM-1630 tapes, as examples. As a finishing touch, the machines are on wheels, so they are mobile, allowing operators to roll AMICS through the aisles of an IMES vault or transport one easily to an asset-holder’s archive location.

READY FOR ACTION

Koszela reports that Nick Allen, UMG VP, asset and archive management, initially put AMICS to the test with a 4,000-piece collection of assets from a prominent rock band of the 1970s and ’80s. Processing took just two days, and within two weeks, Allen and his team had the metadata organized in the database. Previously, the entire process would have taken three months or more and required extensive labor, so using AMICS cost about one-tenth as much, Koszela estimates.

AMICS now enables IMES to truly live up to its credo, Koszela says: “Our work is at the speed of entertainment, we like to say, which means when we get asked for a Kool and the Gang single, they don’t have to wait three weeks; they can get it tomorrow afternoon.”