The Broadway production of Hair is infused with a rock ’n’ roll energy, as designed by Acme Sound.

While most tourists flock to New York City to gaze upon the Statue of Liberty, see the metropolis from the Empire State Building’s observation deck or traverse through the throngs of people milling about Times Square, taking in a Broadway show is always high up on their to-do list. And there are plenty of shows to see — from newer performances like Billy Elliot to revivals such as Hair and South Pacific — many of which are continually sold-out, a boon despite the current economic climate.

Mix checked in with four Broadway sound designers, each of who are tasked with creating a sonic symbiosis with the show’s performers and audience, an energy that these engineers seek to harness and communicate.

Tap Your Way Through ‘Billy Elliot’

Billy Elliot, which cleaned up this year with 10 Tony Awards including Best Musical, features quite a lot of young people in the cast and, as you’d guess, a lot of dancing — particularly tap. Paul Arditti, who won a Sound Design Tony for the show, says that amplifying the tap dancing over the orchestra presented one of his biggest challenges. For example, the actor playing Billy already wears two wireless mics throughout the show to pick up his vocals. Just before “Angry Dance,” Billy pulls on a pair of track pants that contain another sewn-in wireless pack connected to two mics, one down each leg of the pants. These mics pick up his tap-dancing for this number. However, this setup proved impractical for all the other tap sections in the show because the dancers had bare legs or quick costume changes.

“So I developed the idea of a tap floor, in which the entire stage is peppered with pickups, set into the deck just underneath the parquet flooring,” says Arditti. “There are actually 96 piezo-electric pickups, which are painstakingly wired back to a Yamaha DM2000 under the stage. This console provides phantom power, EQ, compression and gating, and allows us to split the stage up into tap zones. So parts of the stage can be live and other parts not amplified at all. The output from this console feeds a stereo pair of channels in the [DiGiCo] D5T [the show’s main console]. The advantages of this system are that the tap sound is entirely independent of the vocal and musical sound, has huge gain before feedback and is surprisingly immune to non-tap-foot noise.”

Trent Kowalk (Billy) and Stephen Hanna (older Billy) perform in Billy Elliot, which was sound-designed by Paul Arditti.

Photo: Carol Rosegg

The show is mixed on a 128-input DiGiCo D5, a departure from the 132-input Cadac J-Type used on the London and Australian shows. “Much as I love the analog sound from the Cadac, I opted for the programmability, reliability, future-proofing and size of the DiGiCo,” Arditti says. “It’s worth bearing in mind that the actor playing Billy Elliot changes every show — sometimes during the intermission if he’s injured or unwell. So a console where each individual’s mic EQ can be recalled from a library, adjusted live and resaved at the end of the performance is a good thing to have.”

Wicked sees sound designer Tony Meola spec’ing a Meyer system and two Cadac analog boards.

Another issue Arditti and associate designers John Owens and Tony Smolenski faced was the Imperial Theatre’s low stage, which meant that the Meyer UPM-1P front-fills hit the audience at chest level. “Effectively, this means that the front-fills are useless for row B and anywhere further back. I use the downfill [11 Meyer M’elodies] from the center hang in the center of the orchestra to provide the main vocal coverage, whereas I would normally prefer to rely on the front-fills to pull the image down. Similarly, at the sides of the orchestra, most of the vocal energy comes from the main vocal line arrays on the prosceniums [also M’elodies], whereas I would have preferred the front-fills to pull the image toward center.”

Down in the pit, the set machinery took up a fair amount of space. The musical director wanted to keep the band in one place to maintain good communication, so there was no “remoting” of instruments as often happens on Broadway. “The stage extends asymmetrically over the pit, too,” Arditti explains. “Not too much live sound gets out, and we ran the risk of trapping all the sound from the instruments in a confined space. So I designed the pit to be more like a sound studio than a live performance space. We employed a lot of acoustic absorption and screens between sections. We also created two sealed booths for the percussion and drum kit.”

The musicians have Aviom A-16R personal mixers, which are submixed with a Yamaha M7CL-48 under the stage. Arditti is pleased with the band’s sound quality. “Needless to say, it’s not the natural, unamplified sound of a classical orchestra, or even a jazz big band, but it works for Elton John’s music and Martin Koch’s arrangements,” Arditti says with a laugh.

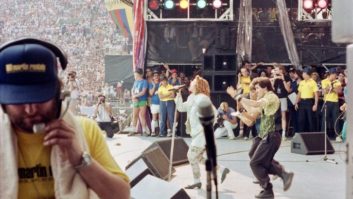

A Rock System for ‘Hair’

Maintaining the energy of a rock concert while keeping sonic clarity was job Number One for Nevin Steinberg and Sten Severson of Acme Sound Partners LLC, designer and associate designer for the Tony Award-winning revival of Hair at the Al Hirschfield Theater. This version actually began as a concert in Central Park in the summer of 2007 to celebrate the show’s 40th anniversary.

“The concert vibe and aesthetic never left the piece; it became part of its DNA from the moment it began,” Steinberg says.

Part of that vibe involves maintaining contact between musicians and cast. Unlike many other Broadway shows, the band is situated onstage and the actors are often found dancing on the bandstand or playing percussion. In addition, the cast moves about the house, inciting protest, asking for money, flirting, etc. “It’s about people interacting with one another,” Severson adds. “The fourth wall, forget it — there’s no separation between audience and cast.”

The Hirschfield Theater was chosen with this in mind. It is built in such a way that the actors can get directly from the stage to the box seats and the balcony without leaving sight of the rest of the house. Also, the audience has access to the stage, where they are invited to dance with the cast at the end of the show.

Acme wanted a high-definition, high-powered system to generate the rock concert energy while preserving clarity of vocals and lyrics. To this end, the center cluster above the proscenium (covering front of house) comprises high-powered L-Acoustics ARCs and high-powered dV-DOSC, additional ARCs for band reinforcement and Meyer Sound CQ-1s. “All the supplemental systems are also capable of high SPL and high resolution,” notes Steinberg. Rounding out the system are Meyer 600 HP subs (floor, rear balconies), L-Acoustics ARCs (proscenium, covering the upstairs audience) and Meyer MICA line array systems (middle of the theater). Hanging off to the sides of the balconies, filling the box seats and areas beyond them, are L-Acoustics MTD108s and MTD112s.

For South Pacific, Scott Lehrer took a more “pre-reinforcement” approach.

JF80 speakers are used as surrounds, filling in from the sides and rear. These are used for sound and special effects, as well as to sweeten the acoustic signature of the room electronically with reverb or delay. “Also, because some of the action takes place in and amongst the seating areas, we sometimes reinforce the signal from those speakers in a mix with the main sound system to envelop the audience in the sound of the vocals,” Steinberg says.

Because of the show’s loud rock sound, there is an entire subsystem of speakers pointed toward the cast and band as monitors, including Meyer UM-1s. But as stage space is limited, Acme also uses many smaller speakers, some built into the floor of the stage, some flown overhead and from the sides, and some distributed in and among the band.

Every cast member has a DPA 4066 headworn boom mic with Sennheiser SK5012 and 5212 transmitters mated with Sennheiser EM3532 receivers. The mics are fairly small and lightweight, which Severson says helps withstand the intense choreography. It also frees the mics from interaction with hats, unlike head-worn lavalier mics. And because the vocals are sent back to the stage (a somewhat unusual practice for Broadway), the headworn mics put themselves close to the sound source, decreasing the chances of feedback.

Un-Reinforcing ‘South Pacific’

Uptown at Lincoln Center, audiences have been flocking to the Vivian Beaumont Theatre for the lavish revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s classic South Pacific, complete with the show’s original 32-piece orchestration. “[The production team] wanted to feature that and feature it in a way that harkened back to the old style of doing musicals, pre-reinforcement,” says designer Scott Lehrer, who won the first Tony for the show’s sound design in 2008. “Everybody wanted it to be a quieter, more intimate show than is typical on Broadway these days.” Lehrer points out that today’s audiences expect a sound that’s far beyond what can be achieved without reinforcement. So the goal was to use available technology to make the audience perceive the sound as more natural than most Broadway shows.

One trick was in miking the orchestra. Lehrer and associate designer Leon Rothenberg used one set of microphones to close-mike the instruments — the typical Broadway procedure — for the big production numbers. But they used a second set of area mics to get a more lush, natural sound on many of the other songs. Sometimes the two sets were mixed for various effects. For instance, in a highly dramatic moment during the overture, production mixer Marc Salzberg switches from the area mics to the close mics as the stage opens to reveal the orchestra to the audience, making the sound feel suddenly more present.

The area mics are mainly Sennheiser MTH8040s, similar to the Sheffield CM Series used for classical miking. The close mics include Royer 121s on the brass, Sennheiser MKH40 condensers on the reeds and Sennheiser MKH800s on the strings — “a medium-diaphragm, multipattern microphone with a beautiful sound,” Lehrer describes.

Another of Lehrer’s techniques is his extensive use of surround reverb. The Beaumont is a fairly dead house acoustically, so 15 years ago Lincoln Center installed the SIAP artificial reverberant system, with more than 100 speakers placed on the theater’s ceiling and rear walls. Lehrer bypassed the SIAP system and wired the speakers to the 10 outputs from two Lexicon 960 reverbs in surround mode. “I was feeding somewhere around 85 speakers with two different surround room algorithms,” Lehrer says. “It was a very rich sound.”

The 1,100-seat Beaumont has a thrust stage rather than a proscenium, creating an added challenge with the delay systems as the actors are being tracked in more 3-D space. “There’s literally hundreds of cues that mixer Marc Salzberg runs to change the delay times on the actors so that the audience perceives that the sound is coming out of their mouths as they move around the stage,” Lehrer says. For delay and EQ, Lehrer uses Yamaha DME64s: “It has delay matrixes so you can delay every point of the matrix — every group can be delayed to every output. So a vocal group can get delayed separately to every speaker in the theater.” On most shows, Lehrer uses two DMEs, but the number of speakers used in the show was so big that for the first time he used four DMEs. (Lehrer estimates that the average Broadway show has 50 or 60 speakers, but he’s working with about double that number, including the SIAP speakers.)

The actors employ headworn DPA 4061 lavalier microphones with Sennheiser 5212 transmitters and 3532 receivers. “For the woman who played Nelly, because she has that famous song, ‘Wash That Man Right Out of My Hair,’ we had to get a water-resistant microphone,” Lehrer describes. “Countryman makes a lavalier that is very water repellant. So we have two transmitters on her, both with Countryman lavaliers, which resist water much better than the DAP 4061s. At least one of them generally works when she comes out of the shower.” Lehrer also double-mikes the character of Emile, an operatic baritone, with a second lavalier on his chest to capture the rich bass frequencies that the head-worn mic misses.

Lehrer favors d&b audiotechnik C7 speakers, which comprise the center cluster. “These are my favorite speakers to use,” Lehrer says. “They’re incredibly neutral, beautiful-sounding speakers.” He also chose d&b Q-Series amps for left/right and main delay systems.

A ‘Wicked’ System

Wicked, the early story of the Wicked Witch of the West from The Wizard of Oz, continues to be one of Broadway’s most popular and long-running shows, a best-seller since its opening in 2003. Fitting the size of its popularity, the show is in one of the largest theaters on Broadway, the 1,933-seat Gershwin. Designer Tony Meola has a lot of air to move, so he chose larger Meyer loudspeakers to reach the back of the house. He finds Meyer speakers and the Meyer SIM equalization system get him the most real and natural sound. “I’m known as the more natural sound designer of my peers,” says Meola. “I believe that the strongest thing we do in the theater is live, and the more technology we put between the actor and the audience member, the farther away we get from what we do the best.”

The P.A. is split into two systems, one for the vocals and another for the orchestra, as he has found that each group sounds better with different loudspeakers. Also, Meola wanted the instruments’ sounds to come from the orchestra pit rather than over the proscenium, and the vocals to come from center stage where the actor stands rather than from left and right. “I blend the line arrays over them and the front-fills under them, and sometimes a little bit from left and right so that the image is more on the stage,” Meola explains. For vocals, he hangs Meyer M1D line arrays at the center cluster, and places M2D split line arrays up and down stage left and -right for the orchestra. Meyer UPM1Ps and 2Ps are hung to provide fills under the balcony. There are additional UPM2Ps used as delay units for the vocals hung in the balcony. In the past, Meola would have used numerous Meyer UP-As or CQ-1 or 2 speakers to reach the back of the theater, but line arrays have a further reach, rendering the extra loudspeakers unnecessary. To EQ the system, he uses Meyer Galileos, and the Meyer RMS system to monitor the cabinets.

Meola uses two analog consoles for mixing — a 58-slot and a 32-slot Cadac J-Type. The console is highly flexible because the output modules are a VCA, a submaster above that, and a dual matrix. “The move into using VCAs is very easy the way it’s cued,” says Meola. “You can change aux send, pre, post, change EQ — all with the push of a button. And the windows that open and close are very user-friendly.”

Meola uses the first Cadac console for the vocal mic, the computer control modules, 14 VCAs that change during the show and reverb returns. The second has mostly orchestra and sound effects. Drums and percussion are submixed on a Yamaha DM-1000.

The orchestra’s monitors are mixed on a 56-input Yamaha DM2000. It’s a big show, so many of the musicians, particularly those with electronic instruments, are using individual Aviom monitors that allow them to control their own mixes. The pit lacks space because there is scenery in it, so Meola has the percussionist and harpist miked remotely in two separate dressing rooms. (Also, it’s very difficult to mike a harp without picking up everything else in the space.) “Very often, scenic designers take orchestra pit space as if it were stage space,” Meola says. “You can weigh what’s worth it and what’s not. In the case of Wicked, it certainly helps the story.”

And helping the story and its plotline — as well as its connection to the audience — are demanded to keep show running. Therefore, it’s no easy feat what these sound engineers are able to accomplish — despite small theaters, demands from actors and directors, and competing with set space — using their own artistic creativity and technology prowess to create compelling and exciting sound designs.

Gaby Alter is a New York City-based writer.