By Brian Smithers, Program Director, Audio Production, Full Sail University

When the COVID-19 pandemic effectively closed campuses across the country, our period of adjustment was about a nanosecond. I lead an entirely online bachelor’s program in audio production, so our students do their schoolwork from home to begin with, and working from home has actually been pretty nice, all things considered.

While my colleagues in Full Sail University’s immersive campus-based programs made collaborative efforts to quickly—and as seamlessly as possible—make the transition to delivering quality instruction in a different forum, in Audio Production we quickly realized that we were the least-weird thing in our students’ lives.

As heavy a lift as it was to figure out what, say, a Show Production final project looked like online, our campus educators had the benefit of an in-house Learning Management System (LMS) that their students already used and their colleagues’ experience of ten years of teaching audio online. At Full Sail, we started teaching Music Production online first, and then about six years ago we added the online-only Audio Production program, so we were fortunate to have all that experience with distance education under our belts.

It wasn’t easy when we first went online. We joined a field dominated by other platforms and MOOCs, in which most content was delivered as recorded lectures that were indistinguishable from campus instruction. We quickly realized that was not the way to create engaging online curriculum.

Obviously, there’s no single best way to teach online, but we approached it as its own medium with unique strengths and weaknesses.

Among its great strengths is the ability to engage with students asynchronously, allowing each of them to integrate school into their own busy lives. Video lessons, readings, exercises and projects may still be sequential, but they are not scheduled. That turns into a disadvantage when a student has a question 20 minutes before a Sunday midnight deadline, but that disadvantage turns into another great strength—online learning builds skills in project management and independent problem-solving.

We do still include synchronous lessons, lectures, demonstrations and/or help sessions weekly in order to offer real-time interaction and a sense of community for our students who are able to attend. All such sessions are, of course, recorded for later viewing.

If your class sizes are reasonable—which they need to be—online instruction can become potentially more individualized than face-to-face instruction. Teaching on campus, I was almost always talking with groups of students, but online I instituted one-on-one, real-time oral exams in one course in Audio Fundamentals, a labor-intensive experiment with rich rewards. All of our faculty give their students personal feedback on their work, and a number do it via individual videos, which, while time-consuming, are obviously a great way of bridging the miles.

If your class sizes are reasonable—which they need to be—online instruction can become potentially more individualized than face-to-face instruction.

We work to build feedback cycles into as many assignments as possible, inducting students into the same “try/fail/analyze/repeat” workflow each of us turns to our advantage in our creative lives—no easy feat in our accelerated programs, but, again, well worth it for the benefit of our students. Modeling constructive analytical feedback is essential to building self-sufficient engineers, producers, sound designers, editors and mixers; making online students feel part of a community of common practice is equally essential.

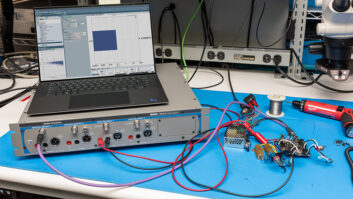

Known as Project LaunchBox, all of our students purchase a standard technology package customized to their degree program, so they have a worthy laptop, interface and mic(s), along with access to the same DAWs. This not only simplifies the process of creating and delivering online curriculum and reviewing student work, it was critical to the success of our pandemic response for campus programs, as we weren’t entirely dependent on the gear and software in our studios and labs on campus.

Part of that package is a pair of Sennheiser HD-280 headphones, which our faculty also have, so we always know we have a common listening reference. If a student submits something mixed on their bass-hyped popular-brand headphones, we can get them to listen to it on the 280s to hear where they went wrong. In our Audio Production bachelor’s degree program, students also get a pair of small studio monitors so they can learn to hear the difference between mixing in the air and mixing in cans.

To extend the business day and to reach other time zones, a dedicated team of faculty devotes their time to staff two evening support lines—one for technical issues and one for musical questions—that supplement our existing LMS technical support team in order to address our audio students’ specific needs. This is one of many ways we’ve responded to student feedback over the past 10 years, as they told us the flexibility and support they need to deal with time zones, work schedules and family life.

After 30 years of telling students where to be and when, working with online students required us to reconsider our approach. After 10 years of doing it online, we’re still learning, growing and innovating to meet the needs of our students.

Brian Smithers recently celebrated 20 years at Full Sail University, where he is the Program Director of Audio Production.