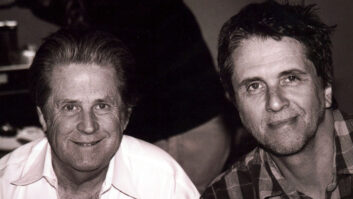

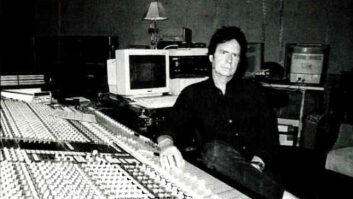

There’s a real art to making successful transitions, whether in a career or in a life. Brian Malouf has managed to gracefully make more transitions than most: from musician to busy live sound man, R&B hit mixer, successful alt-rock producer/engineer and talent scout. These days he combines what he’s learned from all these roles into his job as Senior V.P. of A&R at RCA Records, where he supervises recording projects and does hands-on producing and mixing for artists such as Lit, Danielle Brisebois, Eve 6, the Verve Pipe and Hum.

Malouf’s credits range wide. He was a recording engineer on Michael Jackson’s Bad, mixed Extreme’s monster ballad “More Than Words” from their multi-Platinum Pornograffitti, and mixed singles for Madonna, Expose, Roxette, Slaughter, Gin Blossoms, Pearl Jam, Ugly Kid Joe and Bon Jovi, among many, many others. His more recent work includes mixing and co-production on Everclear’s breakthrough Sparkle and Fade and mixing for Kid Rock, Tonic and Lit’s A Place in the Sun.

A thoughtful fellow with a realistic point of view and a penchant for detail, Malouf seems to take nothing lightly. This is not to say that he doesn’t laugh or have a sense of humor-he definitely does. But his serious demeanor makes it obvious that his natural inclination is to think before acting.

Malouf is a bicoastal hybrid. He’s originally from Los Angeles and is now based in New York City; on any given day you’re likely to find him behind a console in either city.

How did you get your start in L.A.?

I was a musician-a drummer. In high school I also experimented with other instruments; I played trombone and euphonium and upright bass. I learned a lot of instruments because I wanted to be an arranger as well as a musician. But in college I went back to playing the drums.

You knew early on that you were interested in musical arrangements.

Yes, I wrote for the big band in high school and got into learning band instruments. But doing that actually ill-prepared me for college; when I applied to Cal State Northridge, I was rejected. I’d applied as a percussionist, going back to what I thought I knew, but I didn’t really know it very well at all. Getting rejected was a real turning point for me. I spent the summer after that studying, re-took my juries and got into the school. By the time I finished at Cal State Northridge, I was the principal percussionist in the symphony orchestra, which was the principal chair of the department.

Meaning you played tympani and hand percussion?

Just tympani. That’s what you work toward as a percussionist. Every section has a principal player, the first chair, and the first chair in the percussion section is tympani.

So by the time you graduated you were first chair.

Right. And entertaining the notion [laughs wryly] of being a legit symphonic percussionist. I was almost good enough to do it, but I eventually got tired of counting rests. In my fifth year, I left school and went back to playing drum set in bands.

I was always the guy in the band who did the P.A., and liked that sort of thing. So when I quit playing, five or six years later, I went full force into sound engineering. I did live sound at the Bla Bla Cafe and for a couple of Top 40 bands who could afford to rent a P.A. from me.

You had your own system?

Actually, I had three. I rented some equipment back from the band I’d just left, I bought some on my own, and I built three systems. I was making good money, and I kept very busy. During the day, I also apprenticed with Dave Jerden at El Dorado Studios. He’s the guy who taught me studio engineering. I apprenticed with Dave for about a year, during the time he was working with Brian Eno and Bill Laswell and Material.

I left around ’81 and went to Can-Am Recorders. The place was for sale; Larry [Cummins] was very disenchanted with the business and was ready to call it quits. Then I showed up one day, with all this energy and all these ideas for how to rework the room, and we set about doing that. We tore the whole studio apart and rebuilt it. I was the chief engineer, the assistant engineer, the gofer-I was everything and so was Larry. We built up quite a nice little clientele.

Michael Jackson walked in one day with his brothers, which was a pivotal thing for me, because that’s how I started working with Michael. He came to me on one of their sessions and said, “Hey Brian, I want to come back tonight and do my own stuff. Can you do it with me?” And that was the beginning of working with him for a year and a half on the demos that were the beginning of the Bad album.

It was pretty heady stuff, very exciting, and it led to lots of other things. I remained at Can-Am for ten years, until in ’91 when I started doing more work at other places.

Working with Michael started you off on a career in R&B and pop. But, unlike many other engineers, you’ve been able to transition into rock; you didn’t stay pigeonholed as just an R&B engineer.

Actually, I was severely pigeonholed, and it was R&B and pop for a long time. One of the things that helped me break out of that was a group called Slaughter-that was really the first rock thing I did. They called me because they’d heard my R&B stuff and they wanted a big fat bottom end on their record. I mixed seven or eight songs from that record, and the songs that I mixed were the singles that broke that band. And then I did the “Even Flow” mix for Pearl Jam that helped get them rolling, then Everclear and Lit. I’ve managed to get in on the ground floor with a lot of rock acts. Now it seems like that’s all people call me for, so [laughs] I’m pigeonholed again.

How did working for a record company come about?

I told my manager, Steve Moir, that it was something I was interested in. At that time I’d been in studios day and night for 13 years, and I thought, “Maybe it’s time for me to do something different; maybe a more social existence would be preferable for the quality of life.”

But now you spend 13 hours a day in the office and the studio, right?

No, I’m in clubs seeing bands at night, and in the office or the studio during the day, but it’s not the claustrophobic, total studio environment where that’s your hive from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m. That got old for me.

Whereas many people end up in a job by chance, you’ve made very conscious decisions about your life and career.

Yes. Well, the breaks happened, but one of the things I’ve always believed in is that opportunity knocks for all of us. Maybe not regularly, but often enough to take advantage of if you’re prepared. It started in college, when I wasn’t prepared to take that first jury. I decided that was the last time I’d be caught with my pants down. So from the moment I got into college until today, I’ve been prepared for whatever was the next thing that was going to happen. If the Philadelphia Philharmonic had called me on any Saturday, any time after my second year of college, to come and audition for them on Monday, I would have been ready to do it. That meant I had to practice every day, and maybe that phone call never came, or maybe I wouldn’t have taken [the job] once it did, but I was prepared. That’s what I mean by being ready when opportunity knocks.

I also made conscious decisions, sometimes, to take a step back in pay, like when I went from being a live sound engineer to being a studio engineer. I sacrificed a lot of income to go back and become an apprentice in the studio, because I decided that the real future for me was doing studio engineering.

I made a similar kind of reduction when I came to work for RCA. Maybe not that drastic, but it was significant, because I looked at it as an opportunity to do more with my life creatively.

At the time, I’d been an assembly line of mixing, just like the guys today who are doing it. Every day is a new tape, and it’s somebody else’s vision, somebody else’s baby that they’ve brought up from the cradle. You’re handed it for a day or a week, and then it’s gone out of your life. And that’s great-there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s a really good living, and it’s really fun to mix. I loved every minute of it, and I’m very lucky to still be able to do it. But after a while I thought, “God, I’d really like to do it with my own group and work on music that I’m completely accountable for.”

So to prepare to get the job I have now, I went out to the clubs and to the publishers and to the other sources-managers and attorneys-and I began doing my own A&R, either when I wasn’t in the studio or at night after a session was done. Because I wanted to go back in the studio and have fun. Like the first time I took a band into El Dorado because Dave said I could, to get my chops down on a weekend-I took a band in and had the time of my life. I hadn’t done that for so long. So that’s what I did; I looked for acts to produce. That’s when I found 1000 Mona Lisas and Everclear and took them into the studio. By the time the job was offered to me, I’d been doing it for a year already.

You recorded demos with Everclear, and you mixed their hit album Sparkle and Fade. How did you originally hook up with them?

That was a result of a meeting with a publisher named Andy Olyphant whom Steve Moir said I ought to get to know. Andy, who now is in A&R at Almo Sounds, was an up-and-comer. We sat down and played each other a bunch of stuff, and neither of us was particularly turned on by anything the other guy played, although we were being polite and getting along well. As I stood up to leave he said, “I’ve got one more thing to play for you. I’m trying to sign this but my boss doesn’t like it. What do you think?” It was Everclear, and I flipped out. I thought it was the most vital music I’d heard all day-actually, in years.

They had no record deal at the time?

No. Andy wanted to publish them, and his boss didn’t get it. And I said, “I know why he doesn’t get it-it’s a little too rough around the edges. I’ll take them into the studio and make some demos that might sound a little different to him.” So we did. And it was the classic story: They came, they slept at my house, we worked in a little studio out in Westlake Village and came up with some demos that got them the publishing deal. That was right about the time I was going to take the job at RCA and actually had a meeting with Art [Alexakis] for him to come to RCA. But he’d already been excellently seduced by Gary Gersh and was on his way to signing at Capitol.

On to your productions, then. It’s always interesting how people choose to balance guitars vs. drums and vocals. Your records have different placements rather than a consistent style; how do you decide what gets featured?

I always desire to feature the vocal; that’s always my starting point. I try to get it as loud as possible without taking away power from the track. So that’s my focus, and if the placement sounds different from song to song it’s really the presence of the vocal that counts. Some of it is real loudness, and some of it is apparent loudness. And getting apparent loudness on the vocal has, I think, a lot to do with the arrangement that’s underneath it. If a song is arranged in a great way, everything sounds loud. So actually [laughs] the key to being a great engineer is working with a great arranger.

If the vocal sounds back or forward when you compare one mix of mine to another, it’s safe to say that the arrangement of that song forced me to put the vocal where it is. But, always know with me, the vocal was as loud as I thought it could go without ruining the track. And what I listen for is timbre.

What I do in terms of levels and so forth all has to do with the timbre of the individual voice and how it relates to the other elements in the track. Generally, I try to have the bass and vocals be the counterpoint to each other. I try to make the apparent level of each be equal, and everything else hopefully falls in around that. I look at those two elements of the track as the central melodic components.

Not to make an ’80s-type fetish of it, but you get some really cool snare sounds, like on Lit’s A Place in the Sun. Your snares punctuate but don’t dominate, feel good but don’t overpower.

Yeah, I listened to that record the other day and thought, “Oh good!” Some [snares] are more compressed than others. Some of them I really laid it on, just to get the snare to sound unique, like a couple of the tracks that have horns.

What compressors do you use for that?

I do the same things everybody else probably does; like a lot of guys I usually mult off the snare. Then I use the SSL board compressors, and I also use the Distressor-that can do quite a lot. That’s about it. I think I used a JOEMEEK compressor on snare a couple of times on the Lit record.

More info, please.

Well, compression oftentimes does equal punch and impact on drums. But, like with most other things, I really don’t overdo it. Instead I do a lot of mild compression-multistage compression, with each one set to mild gain reduction.

Typically, the dry snare channel will get a touch of either the SSL compressor or the Distressor-not too wacky-and a bit of the SSL gate as well.

I do run all of the drums, in almost every rock mix that I do, through a separate stereo compressor. Sometimes I use JOEMEEK, or there’s a stereo dbx setup that I like, or maybe the Focusrite Red 3, or that stereo Neve [33609] two-rack unit-some sort of stereo compressor that all the drums go through.

On the [SSL] 9000 there are four stereo buses that are selectable from several sources: the large fader, the small fader, and the odd and even effects sends. I’ll send from the large fader directly to bus A, so the exact levels, post-fader, that I’ve got up on the console, are sent to that stereo limiter, and the small faders are freed up to be other sends.

There’s a little compression there, there’s a little on the original track, and then I’ll often route the snare to a separate audio channel where I get kind of crazy with it-distort it, or ridiculously compress it. One of the things you can do for a lot of punch is set a compressor to a very fast attack so it actually clips off the first part of the sound. The very early envelope gets hit really hard, and that combined with the open channel can add up to something pretty cool.

Another thing is, you can get a lot of great snare drum from leakage into the overheads and the tom mics. If you look for the snare sound in a lot of different places, you generally can find what you’re looking for. Which is why I don’t use samples any more-I think they take away from the performance. Sometimes the drum sound on tape isn’t what you would like to have, but you just keep working with it until you get it as likable as you can, and you go with it.

You’re often mixing songs you didn’t record. When you put up a mix, what do you do first?

I put everything up. I put all the faders in a straight line, somewhere in the middle of the fader range-between minus 5 and minus 10-and just listen. I sort of look at it as a big jumble, then with each pass I do little things. I usually don’t start soloing individual instruments for a good two hours. In the meantime I’m looking at the big picture. I’ll do some obvious panning moves, then the pans change with every pass, the levels change with every pass, and the EQs start to change, although EQ is the thing I try to do last. I try to work for the longest time that I can with level, ambience and panning, before I start pressing dynamics or EQ buttons. It varies. On some things, obviously, I press in an EQ or a compressor or gate right away, but generally I try to take as much time with the naked track as I can stand. [Laughs.] I make the music make me do things. I don’t start out doing things from the get-go.

My favorite mixes are when I look at the board and see 12 or 20 buttons pressed on a 96-input console. Because that means it’s well-recorded and well-arranged. And by not pressing all those buttons I’m not introducing all the nasty artifacts of the signal processing.

Do you mix a specific way for radio?

No. I really just mix for the speakers that I’m listening to. What I listen to does indeed affect how it sounds on the radio, though. I’ll often find myself mixing for an hour or so in mono on the little speaker on the Studer 11/42-track machine. That, I think, helps make it sound good on radio. And you’re not so influenced by the panning you’ve done. Oftentimes I’ll find that when I come back to the stereo near-fields after I’ve been on the Studer speaker, things that I’ve panned way out to the side sound really loud. I don’t change that, and that gives my mixes a nice, big stereo feel.

Do you move the Studer closer to you?

No. [Laughs.] It stays wherever it is in the room.

What other speakers do you use?

Ninety percent of the time I’m on Yamaha NS-10 studios.

How do you balance lots of guitars and still keep the midrange under control?

I mostly use the older stuff for equalizing and compressing of guitars: LA-2As, LA-4s, 1176s. On acoustic guitars I love the old RCA [BA6A] compressors.

Guitars are so compressed anyway-there’s nothing more compressed than a distorted guitar right out of the speakers-so you don’t really need that much. Instead, I do a lot with subtractive EQ and panning.

I’ve never considered myself a connoisseur of great guitar sounds. I don’t own 20 guitars, and I haven’t played with every vintage amp. These days, if I’m not happy with the guitar sound, I tend to put it through a device called the Pod [a Line 6 device]. It’s a very convincing digital device that manages to reproduce a lot of really great amp sounds. It has a couple of rotary dials-one that selects the model, described like “Pod Crunch” or “High Gain Brit Tweed”-all these different names. The manual tells you what model amp they’re actually talking about, but on the front are all these generic names, and you just twist the dial till you get a sound you like. I use it on bass as well.

You use it right out of the patchbay? You don’t have to do any level matching?

The Pod does all the gain changes necessary. You can plug a guitar straight into it as well.

Naturally, the cleaner the guitar sounds going into the Pod the more influence I can have on the amp sounds coming out-I’m not always able to effect exactly the sound I want. But between EQ, panning, compression, and spatial things like chorus and flanging, I can pretty much get what I want. However, I’ve never considered myself a true expert on making guitar sounds from scratch; I generally rely on the player.

When I’m recording a guitar, I really just try to get the full range from the speakers that are being played through. I set up a couple of mics and try to get one to capture all the low mids, and one to capture all the highs. I blend those, and there you go. I never record a guitar with any EQ and never with any compression. Unless, of course, it’s totally clean, and then I can do whatever I want. [Laughs.] It’s open season on the guitar if it’s a clean sound.

Your vocal sounds tend to be dry and present with a lot of impact, but they avoid that danger zone of knife-edged brightness. What do you do to create that necessary presence?

I find that dry vocals cut through without much manipulation. When it’s really dry, you naturally have a very direct-sounding instrument. In a rock band most everything else you’re putting up has either gone through another transducer before it hits your microphone, or the mic is at a greater distance from the source (i.e., a room mic on a drum). Even the close mics on a drum set can’t be as close as when the vocalist’s lips touch the windscreen. So a dry vocal will naturally cut through pretty easily without much else going on.

I think I pretty much do the same thing as most people. One of the great things about being an A&R guy is that I get to watch the other guys mix. I’ve actually picked up on a lot of tricks and techniques that way, like from Tommy and Chris Lord-Alge. But, of course, nobody can make a mix sound like them. You could copy down every one of Tom’s settings, from front to back, and try to do it yourself, and it won’t sound anything like him. It’s the same with anybody else-it just doesn’t work the same.

But, that said, I do pretty much the same as most people. But what I don’t do is much of the really super-compression that mixers like TLA will do, putting it through one or more devices and really sucking it in. Although I experiment, I generally find my way with the SSL compressor or an outboard device like an 1176. Or I use a dbx 160X a lot with the overeasy switch for peak limiting vocals-I think that compressor design is still pretty tough to beat.

Sometimes super-compression is the answer. I admit I’ve cranked an 1176 to where the gain reduction meter is pinned to left, but that’s the exception rather than the rule.

You’re an SSL 9000 man.

I am. Since I first worked on one, about four years ago, I haven’t worked on another console.

What are some of the differences between recording in New York and L.A.?

One of the first things an engineer notices is that there’s a lot less in-house outboard gear in New York. A really well-equipped studio in New York won’t compare to an average well-equipped studio in L.A. The second thing you’ll notice is the rate. In New York it’s much higher than you’d expect, and it’s not always negotiable.

There are far fewer studios per capita in Manhattan; the competition in L.A. is quite a lot higher, and therefore, I think, the studios are all in all better run. That’s no slight to the studios I work at here, because they’re all very well-run, but there aren’t as many to choose from as in L.A.

Obviously you have a love for emotional rock and an appreciation for clever lyrics. What else are you looking for in a band?

You always look for a songwriter who writes melodies that you can remember-that combined with the lyrics become hooks. Then I always prefer to sign a band with a killer drummer. And also, I like to see two stars on stage, I like to have Mick and Keith, John and Paul, Axl and Slash. A lot of my favorite rock bands have two stars in them-it’s great to have at least two focal points.

I like fresh chord progressions-I love it when I get surprised by a change, and I love innovative rhythm tracks.

Your job is not an easy one. It’s pretty rare to find all that.

[Laughs.] Well, actually any two of those things will do!

PRODUCER OR CO-PRODUCERThe Verve Pipe: “Her Ornament” on Great Expectations soundtrack Atlantic, 1998)

Lisa Loeb: “All Day” on Rugrats: The Movie soundtrack (Interscope, 1998)

Everclear: Sparkle and Fade (Capitol, 1995)

Ce Ce Peniston: Finally (A&M, 1991)

Jean-Luc Ponty: Storytelling (Columbia, 1989)

SINGLE MIX OR REMIX ENGINEERTonic: “You Wanted More” (Universal, 1999)

Kid Rock: “Bawitdaba” (Atlantic, 1998)

Eve 6: “Inside Out,” “Leech” and “Tongue Tied” (RCA, 1998)

Harvey Danger: “Flagpole Sitta” (London, 1998)

Pearl Jam: “Even Flow” (Epic, 1994)

Lisa Loeb and Nine Stories: “Stay” (Chrysalis, 1994)

Celine Dion: “Next Plane Out” (Sony Music Canada, 1993)

Gin Blossoms: “Until I Fall Away” (A&M, 1992)

Slaughter: “Fly to the Angels” and “Up All Night” (Chrysalis, 1992)

Seal: “Crazy” 7-inch extended version (Sire/Warner Bros., 1991)

Roxette: “Joyride” (EMI, 1991)

Gang of Four: “Satellite” CD single (Polydor, 1991)

Extreme: “More Than Words” (A&M, 1990)

ALBUM MIX ENGINEERDanielle Brisebois: Portable Life (RCA, 1999)

Lit: A Place in the Sun (RCA, 1999)

Expos,: Expos, (Arista, 1992)

Amy Grant: Heart in Motion (A&M, 1991)

Madonna: I’m Breathless: Music From and Inspired by the Film Dick Tracy (Sire/Warner Bros., 1990)

Jody Watley: Larger Than Life (MCA, 1989)

Ofra Haza: Desert Wind (Sire/Warner Bros., 1989)

Kenny Loggins: Back to Avalon (Columbia, 1988)

Michael Jackson: Bad (Epic, 1987)

Manhattan Transfer: Vocalese and Live ’86 (Columbia, 1985 and 1986)