really wanted to be the first club with a resident entomologist,” laments John Hood over a cocktail at Giacomo’s on Espanola Way in Miami’s South Beach. “Everyone has these static displays in the windows. I wanted to put an ant farm into one of ours, and maybe a grasshopper exhibit in the front lobby. But the entomologist I had lined up backed out. He said the volume would have a bad effect on the insects.”

He pauses, turns from his Heineken and asks, in earnest, “How many clubs do you know that have a resident entomologist?”

Hood is one of South Beach’s many scenemakers, one of those evanescent pseudo-Svengalis of hipdom who create concepts that move from club to club along the Beach. At that moment, he was working for the Chicago-based owners of crobar, a new club located in the Cameo, a former art deco movie house on Washington Avenue. As late as the night before its already postponed opening, the crobar itself was something of a human ant farm as 180 workers tried to paint, weld, hammer, solder and slam the still-unconnected club components together-to little avail, as it turned out. The opening itself was horrifically mismanaged, and welders were still working two hours after the scheduled 10 p.m. opening time.

By contrast, Steve Dash, the designer of crobar’s sound system, was a node of tranquillity in a sea of crazed, desperate bustle. “I’m ready,” he says calmly. “I just want to see what it sounds like when all this construction stuff is out of the way.”

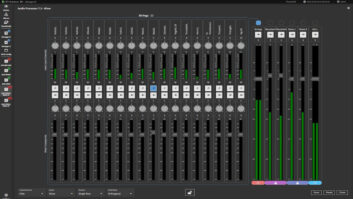

Dash is a principal in Phazon, a New York sound system design and implementation company whose offices are in the same building as Twilo, one of Manhattan’s premier nightclubs and a Phazon calling card. Dash has designed scores of clubs around the world in his 30 years as a system designer. Seven of them have been with Phazon, including Twilo and Liverpool’s Cream and London’s Home in the UK.crobar’s sound system mixes off-the-shelf components with processing and programming equipment from PDS, Phazon’s manufacturing division. It is designed to put out between 119 and 127dB SPL consistently and intelligibly. There are four main speaker arrays with four double stacks at the corners of the uneven-trapezoid-shaped room and two single stacks bisecting it. Each array is loaded with JBL speaker components, including 2450 neo-dymium drivers and four 2405 tweeters. The subs are PDS’s own. The systems use three BSS 388 OmniDrive controllers, Rane GE30 and GE60 EQs, and PDS’s program EQs. The whole system is powered by Crown 5000 and 3600, and JBL 1200, 600 and 300 amplifiers, totaling more than 40,000 watts and stored in their own bunker. The DJ booth, which is raised on a flying bridge at the front of the room, is equipped with PDS monitors, UREI mixers and Technics 1200 turntables.

The signal to the main dance floor can be tapped off, delayed and sent to the inevitable VIP section, which is about a third of the club’s 15,000 total square feet and is located behind a wall of glass overlooking the dance floor. The sound system installation was done by Dan Agne of Sound Investment in Chicago. He chose an Electro-Voice X-Array system with EAW subs. “Both rooms can have their own vibe. The separation between them is actually pretty good,” Agne says. “But the whole place becomes one at the flick of a switch.”

Dash stresses that virtually all of the off-the-shelf components have been modified by Phazon. For example, the bias voltage circuitry in the amplifiers has been revised to increase the S/N ratio and allow the amps to run cooler for longer periods, and the guts of the UREI mixers have been completely rebuilt. Dash also carefully picked components based on their inherent characteristics: For crobar, he specified a 14-inch sub driver (rather than the more widely used 15-inch one), which he says results in a tighter sound for the low end in the approximately 8,000-square-foot, two-story open dance floor. This is all in pursuit of a system whose components are optimized to work with each other, regardless of their origin. “Creating a truly integrated system is the only way to achieve a system that really works well at high SPL levels and remains clear and articulate,” Dash says. The pursuit of perfection, however, is a private one for him. Surveying the dance floor below the DJ platform, he adds, “I doubt anyone is analyzing the system for clarity at 3 a.m., though. Once it’s that loud, the crowds don’t know the difference. But I do.”

But to create a system he is happy with, Dash faced two potential problems, one particular to this installation, the other endemic to clubland.

First, the room’s shape presented a challenge. It’s a bit of an optical illusion. From the floor, it appears to be a relatively conventional and evenly proportioned rectangular box. But viewed from above, the room angles inward at the front below the DJ platform. Thus, the placement of the four double stacks in the room’s corners results in a nonsymmetrical array, which Dash says can produce considerable inherent phase anomalies when the sound waves meet in the middle. That is avoided via processing using the PDS program EQs, carefully tuned using a JBL Smaart Pro analyzer.

The speaker column placement on the floor also represents a significant change from the original plan, which had called for all six units to be flown above the dance floor. “I had shortened the stacks based on that, knowing that the stacks would be vented from the bottom by being flown,” Dash recalls. “When the design plan was revised to put the speakers on the floor, I had to find a way to vent them, which we did by building these perforated steel bases that they’re sitting on.”

The other issue for Dash is not spatial; rather, it has to do with the fact that, as good as the club sound systems are getting, it all comes down to pilot error in terms of their night-to-night effectiveness. “The problem is distortion, stemming from the DJs overdriving the input to the system,” he says. “Records vary in volume, depending upon how they’re recorded and mastered, and as nights go on, some DJs will keep pumping up the volume to keep the energy level up. The system can put out tremendous amounts of power very clearly and cleanly. But if the DJ overdrives the input, the result is distortion, pure and simple, and there’s nothing I can do about that except set the marks on the system and hope they stick to them. But it’s that sort of thing that really makes you appreciate a good DJ, someone who knows how to create a musical vibe and at the same time understands that he’s working with a technical system that has to be respected and approached the same way a recording engineer deals with a high-end console.”