Though development of the Showconsole was initially driven by a very small group within Showco (“Only the president, the owners and myself knew about it,” says Page.), Harrison soon recognized the wider market opportunity for the system and is now separately marketing it as the Harrison Live Performance Console (LPC). Under the terms of its agreement with Showco, Harrison will initially sell the LPC into fixed installations only, leaving Showco a clear field in the sound rental business. Mix asked Harrison’s marketing director Steve Turley and LPC proj- ect manager Kevin Reinen about the similarities and differences between the LPC and the Showconsole.

“Harrison intends to optimize this console for theater and fixed venue markets,” says Turley. “The LPC will be primarily aimed at large theaters, such as those in Las Vegas and on Broadway, plus houses of worship. Software engineer Casey Fleser will be making some software changes that will enable us to better address that market, but the basic consoles will be similar. For example, the Showconsole offers up to four stereo outputs, but with eight output buses, the system can easily be configured for 7.1. Remember, at Harrison we often modify our large consoles for specific clients, so that’s not new for us.”

The LPC shares a common audio heritage with Harrison’s other console lines, but there is not much carryover in terms of the design and manufacturing process. “Most of the LPC manufacturing is surface-mount,” explains Reinen. “Also, we went to a PCI-based system with this console, whereas the SeriesTwelve is a Nubus platform. Some of the circuits for the LPC audio cards are older Harrison designs, but that just makes the console sound good!”

Though Harrison’s network serial protocol is proprietary, the LPC is based on a standard hub-type network architecture. Hardware engineer Michael Webster notes that all connections are made with Ethernet-style jumpers, easing field maintenance. The four-conductor Ethernet cable carries clock, sync line, data in and data out signals at Ethernet speed, with a 160 megabits/second capacity. Updates occur 240 times per second, every 11/48-frame, resulting in 11/44-frame accuracy.

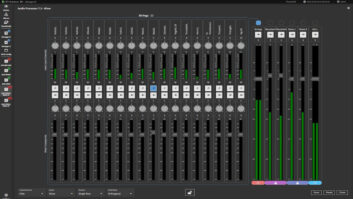

“GRUNT” DISTRIBUTED PROCESSORSAll of the LPC’s control surface faders and pots are motorized, and recall and calibration functions are controlled by locally mounted “grunt” distributed processors that constantly take data snapshots of the local control surface. A so-called “concentrator” card queues all of the grunt snapshots and sends them back to the PCI card in the correct order. The PCI card then instructs the audio processing rack via a copper or fiber-optic link as to which audio channels to update. Digitally controlled analog circuitry then changes the analog EQ, or whatever parameter is being adjusted by the engineer.

Because all electro-mechanical devices can “drift,” the reboot process automatically recalibrates all of the console’s pots and faders. The grunt processors run all of the pots and faders to their maximum and minimum excursions and then reset the zero marks, a process that takes less than 15 seconds. Thus, any stored parameter may be recalled with exact digital accuracy, even if the physical control has drifted from its nominal center. And cues created on one LPC may loaded onto another LPC and recalled with absolute accuracy.

“There’s a zillion motors in that thing,” laughs Turley, commenting on the digital control surface’s analog-like weight. “The internally mounted power supplies have been removed in the latest versions, but it’s still pretty hefty without them. The board has to be roadworthy, so it can’t be a lightweight console made of plastic and stuck together, it has to be pretty solid. This console has a lot of steel in the frame to make it absolutely bulletproof.”