When Mix first decided to investigate the making of a few new live CDs from different musical genres, we didn’t know how each had been recorded, so in a sense this is a random sampling of discs that sounded interesting to us. It was only after we began interviewing the engineers that we discovered a trend: There are a lot of musicians out there who are making live CDs using modular digital multitracks (MDMs). From what we can glean, most of the traditional high-end mobile recording companies are still thriving in the face of competition from engineers using less expensive bare-bones setups rather than remote trucks. (Of course, many trucks also do MDM recording, too.) In fact, it seems as though the MDM revolution has simply increased the number of acts who consider making a live recording, and it appears that conventional studios have been the unexpected beneficiaries of this phenomenon-all those ADAT and DA-88 tapes have to be mixed somewhere! If the following article seems inordinately weighted toward projects done on MDMs, it’s really just luck of the draw.

TAJ MAHALBLUES WITH A SMILETaj Mahal is more than just a blues/R&B singer. He’s a national treasure, a living storehouse of musical Americana. He was “roots” before it became fashionable; indeed, over the course of nearly 40 years, Taj has done much to expose the deep folk and blues roots that are such a vital part of our national soul. He’s had years when he sold a lot of records and his visibility was high, and years when he had to hit the road with just his guitars to make ends meet. Fundamentally, his music has changed little over the years-he’s still singin’ “the natch’l blues” (though certainly he has broadened his palette, as he experimented with African and Caribbean colors). The past few years have been particularly good ones for Taj, in part because he’s fronting his strongest group in ages, the Phantom Blues Band. There have been a number of highly successful tours, a Grammy, accolades in the press and now…the live album, Shoutin’ in Key, on Hannibal Records. The CD finds Taj in great spirits (no surprise there) leading his crack band through a soulful collection of blues and R&B numbers that range from ageless folk tunes to modern originals. Yes, it’s the blues, but you can almost always hear the smile through Taj’s smoky voice, and his upbeat band-seven pieces including the incendiary two-man Texicali Horns-sounds like they’re having the time of their lives, too.

Shoutin’ in Key was recorded over three nights at The Mint, a venerable L.A. club that has been showcasing local and national blues and roots acts forever, it seems. “Tony Braunagel, who plays drums in Taj’s band, had wanted to make a live album for a while, and I was thrilled to get the opportunity to work with Taj,” says Terry Becker, who recorded the CD, which was produced by Braunagel. Becker was a fixture in L.A. for many years, working with acts such as Jackson Browne, Manhattan Transfer, Patti LaBelle, Strunz & Farah and many others, before moving to Massachusetts to teach at Berklee College. “The Mint is such a great place to hear music,” she continues. “The only problem with it is that it has a really small stage; I mean, it’s tiny, and Taj’s band is pretty big, so they were just stuffed up there. It might have made it a little tougher to record, because of all the bleed, but there was an energy up there that was amazing.

“One thing that made my job a little easier is that they have a control room in the club, right off the side of the stage, so it was almost like doing a real remote with a truck, rather than having me inside the main part of the club. To be honest, I wasn’t crazy about the console they have in there, so I borrowed and rented a lot of really good mic pre’s-Avalons and Neve 1073s-and bypassed the board, because we knew we were going to be doing this on 24 tracks of ADAT. I much prefer doing everything analog, but because of the money involved to get a really good analog setup into The Mint it would’ve been a bit much. But the preamps in combination with the ADAT was fine. The Mint had a couple of Neve 1081 preamps. I had those on the bass, 1073s on all the drums and the horns, and I had the Avalons on Taj, his guitars, all the keyboards and the other guitar.”

The size of the stage was only a problem for Becker when it came to miking the drums. “There was so little room around the drums I used a technique called ‘earrings,’ where you point the mics about a foot off the drummer’s shoulders. Tony was literally back up against the wall; there was maybe six inches from the back of his stool to the wall. For those earrings I had a pair of mics-SM81s-facing toward the toms and snare. I also had Schoeps overheads, but it was impossible to position them exactly where I wanted to because the stage was so small. But those sets of mics picked up a completely different ambience. I had clip mics for the toms, an AKG D112 on the kick, the snare was a 57, and the hat was an SM81. I ended up using ten tracks for drums, and the only things I combined were the toms. I had a track for each of the horns-a Sennheiser 421 on the sax and an SM7 on the trumpet and trombonium; a track for Taj’s guitar, which was done with a combination of a DeMaria tube direct and an SM57 on his amp. On the piano I had Countryman DIs. I miked the organ’s Leslie with a 421 on bottom, and I can’t remember what on top. The club already had its own mounted audience mics, so I had very little control over that, but it was fine.

“I ran everything to 24 and also did a stereo DAT recording, which was helpful for when Tony and Taj and the band went back and listened to the performances. We did three nights, so we had two or three takes of most songs, though there were a couple of changes each night. I have my own monitoring system that I bring which makes all the world of difference to me: I use Mastering Lab 10s and a very large Perreaux 7000B amp.”

When Becker left the project to move to Boston, engineer Joe McGrath was brought in to preside over a few minor fixes (at Porter’s Den and Ultratone Studio) and then the mix, which he did at House of Blues on their API console.

Becker is still glowing from the experience of working with Taj Mahal. “He is such an incredibly charismatic person onstage,” she says. “His energy comes across through everything he does and says. He’s just so wonderful; I had a blast doing this!”

FAMILY VALUESKORN, LIMP BIZKIT AND THE HEWITTSYou gotta love a CD that features a sleeve photo of a tattooed baby’s arm giving us The Finger, not to mention shots of babies smoking, drinking, holding a gun and looking at pornography. (In fairness, we should note that these photos condemn the behavior pictured and are each captioned “No family with values should expose their children to this.”) For the past two years, the Family Values Tour has provided its overwhelmingly young, male audience with hour after hour of aggressive, metalloid, sometimes politically charged rock and rap (with splashes of reggae and the stray ballad thrown in here and there). Each tour has produced a head-banging compilation/souvenir, and The Family Values Tour 1999 disc just came out in May on the Flawless/Geffen label. The disc features performances by Limp Bizkit, Korn, Staind, Method Man & Redman, Filter, Crystal Method, Aaron Lewis & Fred Hurst and a group that are practically old-timers in this scene, Primus. Every fuzzed guitar, booming kick and slurred vocal is immaculately recorded; no doubt it sounds even better than it did in the packed arenas the tour visited last fall. This CD rocks hard.

Though most of the bands are made up of self-proclaimed misfits, miscreants and malcontents (is that the rubble of Woodstock ’99 we see in the rearview mirror, boys?), you can’t fault their choice of mobile recording trucks: Twelve of the 14 cuts on the CD were recorded by the veteran engineer David Hewitt and his son Ryan in the famous Remote Recording Services “Silver Studio”; the two Primus songs were done by Westwood One. The CD was mixed by Brendan O’Brien at Southern Tracks in Atlanta. Quite a pedigree.

“We only did two shows for the tour, one in Biloxi, Mississippi, and the other in Missouri,” says Ryan Hewitt. “The Biloxi one was on Halloween, and it was pretty wild. They’re probably some of the loudest acts we’ve ever worked with. I didn’t have a sound meter, but I’d guess from my audience mics that it was pushing 120 dB. It was definitely the most powerful sound system I’d ever seen in my life. It’s aggressive music, and they really involve the crowd. They encourage the kids to blow off steam, so the crowd noise is great!”

Spoken like a true engineer, Ryan. The Silver Studio, which is one of the busiest trucks in the business, is equipped with a Neve VRM 48×48 console, a pair of Studer consoles, KRK monitors, two Studer D827 48-track and three Sony PCM-800 digital recorders, and an impossibly large selection of outboard equipment for such a compact space. Ryan Hewitt talked about specifics of this recording gig:

“This was a situation where they had band carts-one band would be on and the next band would already be set up on another cart or stage that would be moved into position as soon as the other set was over-the set changes happened in about 15 to 20 minutes, which is pretty good. There were four bands each night, and they were all pretty straightforward except one night we had DMX, which was just a DAT, a couple of turntables and vocal mics. It was all direct except for the vocals [No DMX tracks are on the CD]. The other night we had Crystal Method, and they had their own mixer onstage with all their MIDI gear-MPC 3000s and various synths and loop devices, and they mixed themselves onstage with a little Mackie board, and then gave us a 2-mix. They were great; it sounded really good.

“I believe on this tour we didn’t have to substitute any mics [specially for the recording] because they had a very good selection already. The only thing we added were the audience mics: We had four Audio-Technica 4073 shotguns across the stage looking out at the crowd; they have very good side rejection, so we don’t get too much of the P.A., though we have to roll off a lot of bottom end because they’re sitting right next to the subwoofers. Then, out at the front-of-house position, we put up a pair of cardioids looking at the back of the hall and a pair of omnis to pick up the general vibe of the room-the crowd, the P.A., to make it feel live. So we put up eight mics and we put those onto an 8-track [the PCM-800, Sony’s version of the DA-88], with the audience tracks separated, and then we put a mix of the audience on the Studer multitracks, which are beautiful-sounding machines.

“There were two separate splitters, and they [FOH] would hand us tails from the splits. We called it an ‘A’ stage and a ‘B’ stage, even though it wasn’t a revolving stage the way it was at Woodstock. The ‘A’ set would come down 48 channels of our main snake and into the Neve console preamps, and then the ‘B’ snake or ‘B’ stage would come down another set of 48 channels of copper into another set of preamps that we had preset for the next band. Those were outboard preamps-Millennias and APIs-in a separate rack. For this particular gig, we had those in the truck with us so we could adjust them on the fly if anything was different than it was in soundcheck. The mic pre’s that are outboard would come back to the line inputs on the console, so we could just flip the desk from ‘mic’ to ‘line input’ and have a whole ‘nother set of 48 inputs. Everything was direct-routed. There was only one band that had extra inputs that we had to bus down. Everything else went one-for-one to tape-46 channels’ worth of stuff.”

Asked about the main challenge of recording such noisy aggressive music, Hewitt notes, “Music is music. The main job we have as a mobile recording studio is to get whatever it is they’re playing on tape as well as we can and represent what they’re playing. Whatever is coming out of their instruments is what we put on tape. In a case like this, the difference between the Neve preamps and the Millennia preamps might not make as much of a difference as it would in some other music. But we want to get it down as accurately as we can, so that when they take it into the studio to mix or do fixes, it’ll be exactly what came out of their amplifiers, so they can set up the rig again, stick the same mic on it, the same signal path and punch in.”

I couldn’t resist asking about the “family” aspect of recording the Family Values Tour. “Dad and I work together great!” Ryan chuckled. “I’ve been a drummer since when I was a kid, so I generally like to do the rhythm section, and he likes to do the vocals. The way a console generally gets set up with a rock ‘n’ roll act is kick, snare and hat on the left side of the desk, so I sit on the left side, and Dad sits on the right. Since I’ve been working with him so long and watching how he works, we don’t really have to even talk about it. There’s never a fight about pushing the vocals too hard, pushing the guitars too hard. It’s just there. We always have a lot of fun. We just turn everything on and go!”

TAKE 6 IN TOKYOMORE THAN MEETS THE EARBy now, Take 6 is recognized as one of the top a cappella groups in the world, thrilling audiences with their always uplifting blend of soul, gospel and jazz. For their first live album, recorded over three nights at the Blue Note club in Tokyo (where they have a large and devoted following), they enlisted engineer Jon Gass, who had worked on a few earlier studio recordings with the group, to capture the magic in concert. Among the delights on the CD are a Motown chestnut (“How Sweet It Is”), the standard “Smile,” Elmer Bernstein and Mack David’s gritty “Walk on the Wild Side,” a wonderful take on Miles Davis’ “All Blues” (with the singers imitating different instruments) and lots of joyful, harmony-filled gospel.

Offhand, it would seem to be a relatively straightforward assignment for Gass to record the group-six mics on six singers, right? A couple on the piano that sometimes is used as accompaniment. Some room mics? Yet, Gass reveals, “I ended up filling up a 48 [-track Sony digital recorder] pretty much.” That was because on this project Gass elected to bypass the Neve console in the Tokyo-based Tamco mobile truck in favor of recording directly to tape through a rack of Avalon M5 mic pre’s, and “I ended up splitting off the mic pre’s and took all the vocals to tape two ways-with compression and EQ, and without, just in case something was overcompressed or over-EQ’d or something went wrong. It was basically as a safety, but I didn’t use much of [the unprocessed tracks].” Gass has been using Avalon gear since 1990, and also employed the company’s 2055 equalizers on this recording.

On the front end were Shure Beta 87 microphones for each of the six singers in the group, a change from the Sony 800G mics they’ve been using in the studio lately. For Gass, the main challenge was quickly adjusting the preamps throughout the singers’ two performances at the Blue Note. Even though he worked from a set list, “things would get switched around, and at times I had to guess which songs were going to start out really quiet. Some of them start out at a whisper. There was one song where they started it and the crowd and the dishes were louder than they were! But I’ve got markings on all the mic pre’s where I can pick it up 10 dB, and then I also know where to ease it down.” The task is harder than it sounds, since he has to, in effect, “ride” six preamps at once. “It’s a one-finger operation, but you have to move really fast,” he says. “The mix coming off the board was probably a disaster because I was going nuts on the stacks of mic pre’s. But that’s how I like to cut vocals, and it worked well for this.”

Though the recording went smoothly, Gass admits he did encounter some minor difficulties working in Japan. “It was my first time over there, and there were some language problems,” he says. “We got an interpreter from Warner Bros. Japan, and though she knew English and Japanese, I found that engineers have their own language, and unfortunately she didn’t know any of our lingo. Things kept getting lost in the translation; it was pretty nutty. It didn’t end up causing any major problems, though.”

Gass mixed the project on an SSL 9000 at Brandon’s Way; “that’s where I usually work out of,” he notes. He managed to complete about a mix per day there, first working alone and then running the results by the group for approval. Everything on the CD is a complete take of a song, with no fixes. “They’re good guys to work with,” says Gass. “At this point they pretty much trust me on their [vocal] blend. I grew up singing and harmonies have always been a specialty for me. But they understand their strengths and they play to them; there’s almost never a note out of place. So my job was to get that on tape and not mess it up!” he adds with a chuckle.

JOE ELYAT HOME AT ANTONE’SIt’s the year 2000, so that means it’s time for a new live album from one of progressive country’s greatest performers, Joe Ely. Ely’s first live disc, Live Shots, came out in 1980 and commemorated his famous European tour with The Clash. In those days Ely’s band was sort of country’s answer to the E Street Band. Live at Liberty Lunch, released in 1990, featured a stripped-down quartet led by guitarist Mark Grissom. Now, Live At Antone’s showcases Ely’s superb current group, which includes guitars, pedal steel, flamenco guitar, accordion, bass and drums. The focus on the CD is on late-’90s material, with eight songs from Ely’s three most recent studio albums. That’s fine, because this has been a particularly strong era for Ely, whose writing has become deeper and more cinematic as the years have passed. There are also the requisite crowd-pleasers from fellow Texas renegade writers Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and some serious honky-tonkin’ and driving roots rock. But the Mexican influence that has infused so much of his recent material runs deep on this fine, well-paced and nicely recorded set.

Ely lives on a picturesque spread outside of Austin, so the choice of Antone’s, known as “Austin’s Home of the Blues,” was a natural. “It’s a real friendly place for Joe to play so he thought it would be a good place to record a live album,” says Charles Ray, who has done sound for Ely in various capacities for much of the past two decades. “Joe’s normal mode of transportation for the band is an RV, so what we did is we went to his home studio [see Mix, September 1998] and we took some of the gear out of that, put it in the RV and drove it to Antone’s. We parked it right outside the club, ran a splitter snake inside and ran power from the stage so we wouldn’t have any problems with hums or anything. We have four ADAT XTs and we used two of them along with Joe’s BRC [controller] and a time clock to sync everything together. The console was a Yamaha 02R, so it was digital all the way. We used a pair of Event 20/20 speakers to monitor the live DAT reference we made at the same time we were recording. We recorded two nights, with most of what’s on the CD coming from the second night, when the band was really hot.

“The challenge was using the 02R, which is an 8-bus board. Joe wanted to keep it all in 16 tracks. The problem is if you want to go 16 with it, the first eight tracks have to be one-to-one, so channel 1 goes to channel 1 on the ADAT, through 8. Then, on 9 through 16, you can actually assign more than one thing to a channel, so that made the order a little bit strange. I had to go to the second eight to do stereo [submixes]. I took the two floor toms and one rack tom and did two channels with that, made a stereo mix. And I took the three cymbals, two overheads and a hat mic and put them on two channels, so I could pick up two channels. Then, on the background vocals, I split them, because Teye [the flamenco player] sings some, and the bass player sings some, but they never sing at the same time, so I put them on the same track of the ADAT and brought up whichever one was singing on that song. Joe played primarily acoustic guitar, and I put his acoustic guitar on one track and then I used his electric on the same track, but only brought it up on the couple of songs where he played electric.”

Ray used a combination of his own mics and ones taken from Ely’s studio. These included a Beyer TGX50 on the kick drum, an SM57 on the snare, Sennheiser 604 clip-ons for the toms, AKG SE-300Bs on the cymbals, Sennheiser 609s on the guitar amps and Shure SM58s for the lead and background vocals. The bass and flamenco guitar signals came through a Klark Teknik active DI; the accordion was an XLR direct from Joel Guzman’s rig. The room mics, which were placed on the stage on tall boom stands, pointing at the audience and away from the P.A.-were AKG 1000s.

“I had six channels of preamps-four APIs and two Demeters,” Ray notes. “Joe’s vocal and bass went through the Demeters. We tried to record without much compression or EQ, to get the cleanest recording we could. The digital ended up being really good for capturing the dynamics of the music: When it got quiet, we didn’t have to ride the level and we didn’t have any hiss. We tried to keep it clean and simple, and when we got the tapes back to Joe’s [where it was mixed by Jim Wilson] we were frankly knocked out at how good it sounded. It worked out amazingly well.”

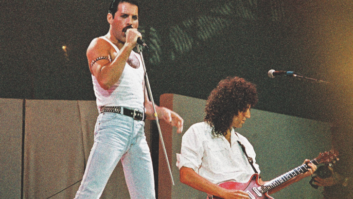

THE CALIFORNIA GUITAR TRIORECORDING THEMSELVESThe California Guitar Trio was formed nine years ago by advanced students from King Crimson leader Robert Fripp’s famous Guitar Craft courses. In their early days, the trio of Bert Lams, Paul Richards and Hideyo Moriya even toured as an opening act for King Crimson on occasion, but by now they have established solid reputations of their own, based solely on their great technical virtuosity, their marvelously sympathetic ensemble work, their imaginative arrangements of both familiar and obscure works, and their increasingly self-assured compositional chops. The CGT haven’t abandoned their Crimson roots, either: They record for the Fripp-run Discipline Global Mobile label, and on their wondrous new live CD, Rocks the West, they’re helped out on half the tracks by Crimson bassist/Chapman Stick master Tony Levin. (Another Fripp associate and one-time member of Adrian Belew’s band, saxophonist Bill Jannsen, also appears on selected cuts.) The CD shows the incredible range of the group’s repertoire, with tunes by Queen (“Bohemian Rhapsody”), Ellington (“Caravan”), The Ventures (“Misirlou”), Mussorgsky (Pictures at an Exhibition), Beethoven (a segment from Symphony No. 9), various sparkling originals, and even a freeform improvised space jam.

The CGT mainly plays small theaters and clubs, carrying little but their guitars with them on the road; usually they rely on house sound mixers wherever they’re appearing. They’ve learned to balance their own sound onstage and can easily direct sound personnel to make sure the balance is right in the house. So it’s not too surprising to learn that for their live CD they handled the recording themselves. “In general, we’ve been documenting our live shows for a number of years now,” says Richards. “Originally we started with DAT recordings taken from the desk, but then we wanted to get better quality and we wanted to be able to mix it afterwards, so we ended up taking an ADAT [XT 20-bit] on the road with us. That’s how we ended up with these recordings. We knew when we were doing these shows with Tony last fall that we wanted to come up with something we could release, so we had the ADATs at the five or six shows we did with him.” Venues ranged from the stately Boulder Theater in Colorado to Henfling’s, a roadside tavern/biker bar in sylvan Ben Lomond, Calif., where “the sounds from the open kitchen near the stage accompanied the music throughout the performance.”

Richards adds, “We’ve really simplified it and made it easy to get a good-quality recording on the road. We submix our guitars onstage using a Roland digital mixer, the VM1000 Pro. That has the capacity for digital outs and has a little box that sends a Lightpipe out to the ADAT, so it makes it easy to hook up to the ADAT without having to go through all the D-to-A converters onstage. So we put the ADAT onstage and go directly into it. We use 60-minute tapes, so we only have to change once, and we usually plan our tape changes while I’m speaking. Hideo Moriya has a tape sitting there ready to pop in, so we don’t have to bother the engineers with it. Hideo also has a little MiniDisc that he records on, so we have a stereo copy on each show.

“Over the years, we’ve spent a lot of time finding a way to get our direct signal not only for the live sound in the room, but for recording, as well. We tried many different types of electronic pickups and different guitars even. We used to be Taylor guitar artists. Before that we used Ovation guitars. Now we’re using guitars custom-built by Ervin Somogyi; he puts out about 20 guitars a year. We outfitted them with a combination setup: Under the bridge there’s an EMF B-Band pickup, which is made in Finland. Then in the sound hole there’s an EMG magnetic pickup, and we blend these two and they go straight into the Roland mixer, and from that into the ADAT. Tony went straight in via a DI into our mixer, then into the ADAT.

“One of the big keys to these recordings, though, was the ambient mics in the room, for which we have to give a lot of credit to our friend Brian Lucey, who mixed the record at his studio in Ohio and was sort of our live sound advisor. He hooked us up with this matched pair of Audix CX-101 large diaphragm mics, which we put up on a shock-mount and then found a strategic location for in the room. The direct sound that we get from the guitars is fairly flat, so it was important to get something from these good-sounding room microphones; the key was the placement. It didn’t work at every place we played, but we had more than enough for the CD.”

Richards and Brian Lucey mixed the tapes at Lucey’s Magic Garden Studio in Columbus, Ohio. “We added a bit of EQ, but mostly left it alone,” Richards says. A simple recording technically, but the guitars shimmer and you can feel the electricity onstage and in the crowd, so it’s a grand success all the way around.

PONCHO SANCHEZPRIMAL PERCUSSIONLatin Soul is the latest CD from Poncho Sanchez, whose illustrious career spans 25 years (including seven with Cal Tjader’s influential Latin jazz group) and encompasses 21 albums as a leader, most for the Concord Jazz label. Latin music has traditionally been recorded live in the studio with minimal overdubbing, so live albums usually don’t sound tremendously different than studio records, but there’s no question that a band like Poncho’s really comes alive in a club, and Latin Soul documents that fact masterfully. On this CD, the veteran percussionist fronts an eight-piece band that is very heavy on the percussion, as you might expect; in fact, even the horns seem to function as melodic percussion at times, with their peppery blasts. Congas, timbales and bongos take center stage with this group, whose fiery Latin rhythms never lag for a second-it’s quite a display of both energy and finesse, as the parts interlock and dance with each other, but never sound cluttered; quite a feat.

Produced by John Burk, Sanchez and pianist David Torres, the CD was recorded by Phil Edwards, whose company, Phil Edwards Recording, has been an important fixture in the San Francisco Bay Area for many years. Though Edwards has worked in every genre imaginable, he specializes in jazz, Latin and gospel dates up and down California. His truck is well-outfitted with a vintage 40-input API console with an API sidecar, Otari MTR multitracks and 2-tracks, Dolby SR and A, UREI Time-Align speakers, the requisite complement of the latest outboard gear, and an impressive selection of old and new microphones. In a concession to changes in the recording industry (read: smaller recording budgets) Edwards has also added 64 tracks of DA-88; in fact, he says the overwhelming majority of work the truck does now uses the MDMs. “Back in the analog days, nobody worried about spending $150 a roll for a half-hour of tape, but now it’s a huge consideration,” he says. “Everyone has to change with the times. And that means MDMs and more and more inputs. I’ve got 72 now and I suppose it’s not enough, but I’m tired of fighting the input wars,” he says with a laugh.

“There’s a perception now that to record a concert all you need is an ADAT, and then you take it home and mess with it in Pro Tools and you’ve got an instant record,” Edwards continues. “Then, on the high end, you’ve got guys who can’t record something unless it’s going through a $10,000 preamp. And there’s a lot in the middle. Doing a remote right still takes a lot of preparation, because there are a hundred things that can go wrong with the cabling and interfacing and all that. I have a truck and it’s self-contained, but it still takes us four or five hours to get it all together, and before you even get to that stage, I spend hours thinking about mics and setups. I don’t know how anyone does it by just throwing things in the back of a room and making it all go; that’s a mystery to me.”

The Latin Soul CD was drawn from two shows three months apart at Yoshi’s nightspot in Oakland, Calif., and the Conga Room in Los Angeles. Edwards recorded to DA-88s, with the mics routed through the API 312 preamps in his consoles. The main console also has API 550A equalizers. Edwards talked about his miking scheme:

“Everything seems to take more mics than they used to. Timbales used to be just a couple of overheads, but not anymore. Now it’s a mic each for two to four drums and a couple of cymbal and they might also have a cowbell and woodblock. There’s this technique called casceda, where they take the stick and hit the side of the drum and it makes this tinny, percussive sound, but if you put a mic right on it, it fattens up. So over the years I’ve been adding a mic on either side [of the timbales], and now I’m doing six to eight mics on the timbales alone. For the overheads we probably used 451s or maybe 460s-small-diaphragm condensers. I had 421s on the drums themselves. I still like miking them over on the fatter side of the drum, but P.A. guys seem to like it on the bottom. For the casceda I usually use these old SM56s, which are a lot like SM57s. They’re good for anything that is really hot and really percussive because they never overload; they have a nice little peak at around 5k. I think on Poncho’s congas, we miked each drum with 421s or 56s. Poncho also played a set of timbales on one song, but we only used three mics on it. On the bongo I used a single 56 underneath, right at his feet.

“For the bass we took two Countryman directs, including one off the back of the head, and we also put a mic on the speaker. Then, depending on the track situation, we’ll either print those on separate tracks or combine them. Then you’ve got three horns: tenor, trumpet and trombone. For the tenor we used a U47 FET; the trumpet, I believe, was an RCA 77 ribbon mic. There’s something that’s very flattering about those mics for trumpets. They roll off very smoothly at about 7k, which is nice. I recently used a Royer on a trumpet player and I liked that, too. On the trombone, I think we used either a 47 or an 87.

“Then there’s the drum kit, and that was pretty much standard stuff: 421s on the toms, 56 on the snare. I don’t do the top and bottom [snare] routine: When I want to get some snap I just put some extra EQ on top. I usually use a KM84 on the hat, and we’ll usually go with 451s on the overheads. I still like a 421 or something of that genre on the kick. For vocals I used an SM85, which is a vocal condenser that’s a discontinued model; it’s very bright. For piano what I characteristically do is three mics: low, mid and high, and on occasion I’ll use a C-ducer. Then I had three or four mics for the audience. In all I probably had 36 inputs.”

Even with all the close-miking, bleed was still an issue; that’s the nature of the beast when so many percussion instruments are involved. Another factor Edwards had to deal with was the plethora of floor wedges that “were lathered all over the stage,” he says. “Plus they had sidefills! So you isolate as well as you can and when it comes to fixes later you do what you can.”

In this case, the fixes (mostly in the horns, which isolated well) and mixing were the responsibility of Ron Davis, an independent engineer who was on staff at PER for five years. Working at One on One South in L.A., Davis transferred the DA-88 tracks to 3324 and then, with the production team, fine-tuned the mixes. Eight of the 10 cuts on the CD came from the Conga Room show, which was the second of the dates recorded. “At Yoshi’s we tried a couple of things in recording the timbales that I wasn’t totally happy with,” Edwards notes. “But at the Conga Room I thought we did everything the way we should have. It’s nice that we got a second chance, because in this business that’s not always the case.”