Brooklyn, NY (April 6, 2018)—While he’s worked with everyone from T. Rex to Altered Images to D:Generation, producer Tony Visconti will forever be linked to the most famous artist he produced, David Bowie—and that creative relationship was the main focus last night at Brooklyn Talks: Tony Visconti with Jeff Slate, an on-stage discussion at the Brooklyn Museum.

The careening conversation touched on nearly all of the 14 albums the protégés recorded together across nearly 50 years, covering everything from how Visconti and Bowie first met in the late 1960s to their excitement at fusing the work ethics of jazz and rock production together for Bowie’s final album, 2016’s Blackstar.

One of the highlights, however, was Visconti’s vivid recollections of recording The Berlin Trilogy—Low (1977), Heroes (1977) and Lodger (1979)—working with Bowie and Brian Eno in Europe and New York.

Visconti took questions from the audience, answering with candor.

Recalling how he first became involved with the project, Visconti mused, “I hadn’t heard from him for a while. He booked the Honky Chateau—Château d’Hérouville. in France. He and Brian phoned me and said, ‘We have this idea based on Brian’s ambient music’ and they already had a concept: ‘We’re going to do rock songs and we’re going to do an ambient side, too.’ With vinyl, you could have a Side 1 and then Side 2 was another vibe, and they took full advantage of this concept.

“They said ‘What can you bring to the table?’ and it was the first time I ever heard that expression. “Roast beef?” I didn’t know what that meant, but I was quick; I caught on. David knew I had this home studio, and I said, ‘Well, I’ve got this new thing from Eventide, I’ve got the only one in the country and it’s called a Harmonizer [H910].’ And they said, ‘What’s it do?’ I started giving them the technical information—you can change the speed but not the—yaaaaaaawn. So I said, ‘It f—s with the fabric of time.’ I should come up with a different phrase, but that’s what happened. They both whooped in the background—“Whoooooo!” I said, ‘You’re gonna love it, we’ll use it’—so that’s what I brought to the chateau.

At the time, Visconti had no idea that he was at the start of a three-year project that would create a remarkable trilogy of albums—but then again, Bowie didn’t know either. Visconti recalled, “Most records, he started out saying ‘We’re doing just demos, I’m not sure this is gonna be an album,’ and that’s how he prefaced this one: ‘Would you mind spending a month with Brian and myself and maybe nothing coming of it?’ Oh right, I would love to spend a month with you and Brian and I don’t give a s–t what happens! It was a great vacation—it was September, the chateau was beautiful and it’s such a beautiful area of France. Sure!

“We started making radical sounds right off—I altered the drum sound immediately with the Harmonizer, which [session drummer] Dennis Davis went crazy over, he loved it. It was the first foray into changing pitch but not time, and changing time but not pitch, and he realized with all the glitches in the machine, he could play it with dynamics. He played the Harmonizer very hard—it would splutter and go brrrrrt!—but if he hit it a little softer, it would go [a diving boom sound].

“So he was having a ball in the headphones. No one else heard this in the headphones—they did initially and they said ‘Oh turn that off! It’s terrible! Ooooh!’ It was only on playbacks that I would go, ‘Let me put the Harmonizer in a little bit,’ and everyone after a few days got used to it. It was such a radical sound. One little bit of pleasure I had was that for months after that record was released, all my record producer friends would phone me up and say ‘Come on, Tony; how did you do it?’ Because I still had the only Harmonizer!”

Visconti noted that throughout the making of the different albums, Bowie always tuned into his surroundings, and that filtered into whatever he was recording at the time, adding an underlying thesis to the work. “David had to go out and soak up the local stuff,” said Visconti. “There was very little of that to do at the Chateau because we were about 13 miles outside of Paris, and he was also going through law problems. He was being sued by a former manager and would often have to go into Paris for depositions and he would come back so pissed off and angry and depressed. And that’s exactly why he called the album Low.”

Massive ‘David Bowie Is’ Exhibition Sheds Light on Artist’s Studio, Touring Life

By the time they reconvened to record the next album of the trilogy, Heroes, Bowie’s outlook had changed dramatically. “In Berlin, he was very happy and he had a lot of confidence,” Visconti recalled. “He and Jimmy—Iggy Pop to you—were really great friends. They would go all over town and I used to go with them to all the nightclubs, which were really radical.”

Keying into the local vibe brought a different energy to Heroes—one that wasn’t always comfortable, it seems. “It was like a travelogue,” said Visconti. “We got a French kind of sound in France, and Berlin, that just turned David into some kind of passive, I won’t say the word…[whispers] Nazi. He got like ‘Wow!’ because the Reichstag is there and Berlin and the bombs and the city was blown out really bad and the studio was where a lot of the propaganda music for Hitler’s rallies was recorded. The whole Hansa Tonstudios made you feel very strange; it was very strange to be there and you could summon that manic kind of energy, that manic aggression that is all over Heroes. There’s no deep love songs on that album; it’s all about being a hero just for one day, the song is about an angry, loser, alcoholic couple. Everyone thinks it’s about ‘heroes’—it’s not! The themes were pretty aggressive; ‘Joe the Lion’ is a pretty aggressive song.

“The nice thing we had was that studio, because [producer] Denny Cordell taught me two things: ‘Get a great drum and bass sound,’ and ‘If you’re in a good room, take it home with you. Always record the room you’re in if it’s a good room.’ And you couldn’t find a better place than the Grand Hall in Hansa Studios, because it could house 100 pieces and a 50-person choir. We had six musicians using that whole space and all the ambience, so I put microphones everywhere. Even when Brian Eno played his little suitcase synthesizer [EMS Synthi A] live, I didn’t take a DI; I put a mic on it, and you could hear the piano, the drums coming down that mic. The whole album is charged with this Teutonic ambience.”

Visconti would later “record the room” for all to use via his 2016 collaboration with Eventide on the Tverb reverb plug-in, which models the acoustics of Hansa Tonstudios’s main space.

While the three albums may be called The Berlin Trilogy, in fact, the last entry, Lodger, was recorded—under trying circumstances—in both Switzerland and New York City, as it dawned on the three collaborators that they were making a set of records.

“Brian and David talked about making a triptych—and that was a great idea,” said Visconti. “We got some great tracks and it’s unappreciated how great some of them are. We actually wanted to go more in the direction of [how we would later approach] Scary Monsters, getting this deeper, glossier, bigger sound. But the studio—Mountain Studios in Switzerland—had such a dead sound. The floor was carpeted, the walls were carpeted and there were acoustic tiles in the ceiling! The purpose of that studio was to record the concerts of the big hall underneath us, where they held the Montreux Jazz Festival. Queen were the only band to successfully rent the hall, so if you had that little cabin of a studio up there and you had the hall, then you had the sound. We tried to get the hall, but we couldn’t get it, so we had to record everything in this little, stuffy, hot room. I have so many pictures of Brian Eno topless!”

Frustrations only mounted once the recording process moved to New York City, where more hurdles got in their way, ranging from a lack of studios available to underhanded moves by an old pal.

“We came to New York and there were some great studios here in those days—Power Station, Hit Factory,” said Visconti, “and we ended up at Record Plant and we wanted Studio A and we got Studio F. Every studio was booked in New York because there were so many people making records. Mick Jagger visited us and he looked around at this dank studio. David played him a track and Mick was putting it down: ‘Eh, that drum. I don’t know if that fill was any good….’ He kept trying to tear it down! I said, ‘Will you stop this? Why are you doing this?!’ And he said, ‘OK, I guess I’ll go up the road and sabotage Joni Mitchell’s album.’ He was playing a mind game on us, and David’s energy was going uh-oh. He didn’t feel good about being in Studio F and then here’s Jagger trashing our work!”

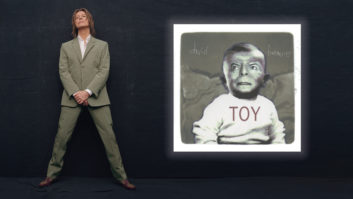

It might have been a lasting sense of uneasiness—and the lukewarm reception to the album—that led to Lodger getting remixed decades later by Visconti, who aimed to bring out more harmonies and percussion: “We were making Blackstar at the time, and I said ‘I’ve got a surprise for you.’ He was working on [the musical] Lazarus, I had some time on my hands and I said, ‘Let me start getting into this.’ We’d always said we wanted to remix it, but when do you book time to remix something? You never do; you book time to make a new album.

“So I did this in my spare time; I got five tracks in good shape, and as soon as I played the first 15 seconds of ‘Fantastic Voyage,’ he just broke out into this big grin. I played it and said, ‘You want to hear ‘Africa Night Flight?’’ He smiled broadly again; he said, ‘This is fantastic…I’m so happy.” So I finished it after he passed away, but he gave it the greenlight, he loved it and approved of the direction it was going in.”

The Brooklyn Talks event was part of an ongoing series of discussions at the Brooklyn Museum, but it also was in support of the museum’s current David Bowie Is exhibition, presenting more than 500 artifacts from across the artist’s career, which runs through July 15, 2018.

Brooklyn Museum • www.brooklynmuseum.org

Tony Visconti • @tonuspomus

Eventide • www.eventide.com