Ry Cooder has made a career out of discovering and shining a light on roots and world music that was created out of the sheer love of expression — and not driven by the dollar. The honesty and magic captured in the grooves have, at times, brought traditionally noncommercial music to the masses. This was most evident with the multi-Platinum success of Buena Vista Social Club in 1997, the result of his trips to Cuba and developing friendships with its musical community.

Photo: Susan Titelman

Born in Los Angeles, March 15, 1947, Cooder made his first notable musical forays as a guitarist playing with Taj Mahal in Rising Sons and with Captain Beefheart & The Magic Band. In 1970, however, Cooder’s self-titled Warner Bros. debut revealed an artistic vision deeply immersed in American blues and folk traditions. He has an utterly unique musical voice and guitar style that is especially clear in his slide playing.

Among the many fine solo albums Cooder put out, Into the Purple Valley, Boomer’s Story and Paradise and Lunch are particular highlights of his earlier work. Beginning in 1980, Cooder started a lengthy career composing, producing and playing music for films, often with Jim Dickinson. Most notable are the soundtracks for The Long Riders and Paris, Texas.

Cooder’s most recent solo album is called Chávez Ravine, named after the largely Latino neighborhood in L.A. that was razed to make way for Dodger Stadium in the late 1950s and early ’60s. The story of Chávez Ravine provides Cooder with a lens through which to view many of the cultural and historical qualities he has grown to love and hate about L.A. The album is particularly a love letter to the vibrancy and rich complexities of the Latino community and its arts, as well as a powerful reminder of how the confluence of big-money private interests and dishonest political agendas can literally bulldoze the lives of poor citizens who happen to be standing in the way of “progress.”

Chávez Ravine opens up with the fantastical image of a UFO flying over L.A., checking things out and trying to catch the vibrant buzz of the music and culture of the city’s Latin community. The playfulness of its appearance provides an avenue with which listeners enter into this world you’ve portrayed on the album.

This is how you envision a record like this. It’s not some history book. It’s about people and sounds of the neighborhood, and that’s a hard thing to get right.

I noticed the flying saucer on the album’s cover art looked almost like a Zoot Suit hat.

[Laughs] Yeah. Well, that was the take of the artist who drew that picture. He thought it was funny. And it is funny, because I thought this must be some Space Vato cat who is out there by himself, and it’s cold and he wants to go where the heat is — where it’s groovy. He’s not trying to scare anybody. Instead of War of the Worlds, the Space Vato actually wants to dance and party and check out these Mexican girls in the neighborhood and so forth.

Tell me a little bit about how some of the songs came together.

The first song, “Poor Man’s Shangri-La,” was just myself, Jim Keltner and Mike Elizondo sitting down and playing; it was totally live. It wasn’t mapped out. I just said, “I’m just going to sing and play and you follow. Don’t stop. If I get through this, it may be good.” Well, Keltner is used to it because we’ve been playing together some 30 years or so. Elizondo, being a kind of new cat for me, grabbed a hold and held on good.

For “Muy Fifí,” I told my son Joachim [a percussionist], “I need some cruisin’ song that feels like we’re boppin’ along in a real low car about 20 miles an hour. You know what that tempo goes like. I don’t know what we’re going to do lyrically, but I’m going to want a song like that.” So that’s when Joachim came up with “Muy Fifí,” which he tooled from pieces of stuff from Havana.

For the lyrics [of “Muy Fifí”], Juliette [Commagere] had the idea of a mother and daughter arguing, because in those days, the Mexican home was busted wide open after the war and the girls started going out, and that was unheard of and parents started going crazy: “You can’t wear your hair like that! You can’t wear a dress like this. You can’t go out with Smiley because he’s got a knife.” Little Willy G. remembered all that stuff from his childhood, and he sat down in an hour and wrote all those lyrics.

For “Soy Luz y Sombra,” we had to pitch it down five whole steps so that Ersi [Arvizu] could sing it. At that point, there was concern that the harmonic structure would evaporate. But what happened was that — at five steps lower — it reconfigured in a funny way and I liked it better. It sounds really soft and open, like a Jackie DeShannon record or something like that.

When you’re working this way, you have to take what comes and work with it. It’s unnerving sometimes, but it’s fun because you don’t ever get too wrapped up in your own preconceptions. There was no way on this record I could predict what was going to happen, so I stopped trying.

Some of the people I found myself working with on this record are tremendously gifted. They’re not famous or have the weight of commerce behind them — just good folks, you know, making a good record here. You would hope that would be recognized. I’d like to think that it is. There’s a lot of talent out there, but it has to be organized now because it’s not so easy. You’re not going to wander into a record company and say, “Flip the deal on this. I’m going to make some good old-time L.A. Mexican music. You’re down for that, aren’t you?” You want to talk about blank looks — eyes rolling. [Laughs]

Fortunately, Nonesuch saw that it was saying something and it fit in with them.

The whole tragedy of ’50s and ’60s urban renewal expressed through the story of Chavez Ravine is one that has countless variations throughout the country. Personally, it reminds me of the gutting out of Beale Street in Memphis.

That was dreadful. Jim Dickinson would give me the update on all this from Memphis: “They’re going to tear down Beale Street and put up a theme park!” That’s what they always do.

Inevitably, it comes down to bad planning, because even if you think the purpose of cities is to deliver the city to development and therefore money, they almost always end up making the wrong call because they could make more money and have more of a unified and expressive city if they would leave it. Wouldn’t you rather go to the real Beale Street and spend your money — if spending money is your real objective — than the Disneyland Beale Street?

The collateral damage [of neighborhoods disappearing] is that they don’t make music like they used to. You just don’t hear it because they just don’t do it.

I think it was [ethnomusicologist] John Lomax who said the worst thing for musicians is the promise of money because it usually means they will stop doing what they did. They will stop thinking about what they did or feeling what they did because they’re almost desperate to replace those impulses with the outer menu to survive, or [they] succumb to the allure of fame, money and power. This is the hidden tragedy.

L.A. is a city of big ethnic enclaves — Mexicans, Persians, Vietnamese — and they don’t play their music. They wouldn’t begin to do it. They just want to do hip hop. That’s it. That’s the whole city now. I have to say it has happened the same down in Havana, too. Up until around 2001, you could hear the music of Cuba in Cuba — other than tourist things, of course, which I don’t count. But now, you get in a taxi and that’s when you find out what people are into. It’s Latin hip hop. I view that as the leading edge of the onslaught of the modern consumerism, because it seems the music gets co-opted to such an extent that it’s like, “Here come the shoes and the jewelry and the product lines.”

You’ve always paid a lot of attention to the sonics of your recordings. This is a particularly fine-sounding album.

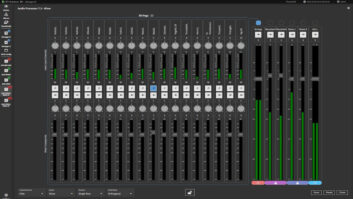

Oh, thank you. Rail Jon Rogut, who is a real good friend of mine, recorded everything. He did a great job — just beautiful — and he went through all kinds of hell doing it. We recorded at the auditorium upstairs at Village Recorders (L.A.) trying to get a dance band sound. We worked with Pro Tools. We sampled every kind of crazy thing and did pitching. The whole thing became like a crazy puzzle that barely fit together. In the end, the challenge we had was that every song was so different from one from another, it looked like it was teetering and just going to fall off a cliff.

Don Smith got it and wrestled the thing to the floor. Don saved this record. Don’s got incredible resources and experience, so he knows what to do and how to make things fit and sound more unified. Well, that was the trick. Because I tell you, at one point, I thought, “If this doesn’t fit together and make sense, then it’s going back to the drawer and I just don’t care.” It wasn’t as if the world or the music industry was saying, “Where’s your Chávez Ravine record? Hurry up! We want it!” I didn’t have that problem. My problem was I wanted to put it out, but I wasn’t going to do it unless it felt good. Don Smith made it feel good. He really made it work in the right arena sonically and made it all thick. There are all kinds of different stuff in there. He certainly made it rock.

After so much time trying to get this right, were there any issues you encountered?

While we were finishing up, Don turns to me and says, “You know, you’re going to have a problem with this record in the manufacturing.” I said, “Oh, God! What now?” He says he knows the Warners’ system is to use Cinram and upload and download the music as files toward manufacturing. Every time they do this, the algorithms shift and you start to lose all this good stuff you like — such as the delays at the top where the voices are, where you’ve really concentrated on making them interesting and good-sounding.

So, of course, I panicked. Here I am, finally three-and-a-half to four years into this and it had to be good. I went to the Nonesuch people and said, “I’m going to show you the difference. You do your thing — that Cinram way — but I’m going to go to JVC and cut a master off glass.” So they made one, and I went with the Cinram version in one hand and the glass master version in the other, and I went out to my Toyota, which is a reasonable way to listen to this. The difference was night and day.

I said to the Nonesuch people, “I’m proud of my work and I need to know that it will go out to the world in the right way because it has no meaning otherwise. It’s not linked to anything. It’s not linked to touring. It’s not linked to merchandizing. I don’t see the back end of this in a natural-fiber clothing line or any such thing. This is it. This is the best I can do. You’re going to understand that I’m not transactional on this. This is my artistic statement and I’m going to stand here and make sure that it’s true.” And they backed me up. We were able to persevere and get this [mastered] at JVC.

But the handwriting is on the wall and I just don’t know if it’s going to be possible to ever have a small victory like that again in the future. I just don’t know what to think. I’m 58 now, so in my lifetime, it’s come to this. I swear to you, I wouldn’t do this if I thought my work had to come out sounding like pillows — like some soft-focused cloudy thing. If we’re going to treat music differently — just as pure commodity rather than real human expression — then I guess it’s another footnote, like the tape disappearing somewhere along the line. It’s weird.

You spent several years creating Chávez Ravine. What was the quickest album you’ve ever made?

Well, the record I did with Ali Farka Toure [Talking Timbuktu] took three days, because that’s all the time he would spend. He didn’t like Hollywood or L.A., and he didn’t like the U.S. at all. He was convinced there were evil spirits in the building. We were working at Western, which was then Cello, and he was convinced the place was full of evil spirits, and he may have been right. I said, “Look, man, we keep the door closed and locked. Nobody’s getting in here.” He said, “No, they’re in the building and if somebody comes in, like a helper or somebody, to bring us something, the evil spirits will come in with them so I can’t stay here very long.” We couldn’t argue with Ali Farka because he’s a very tough guy — a rough, insistent, dominating character. So you take three days and that’s enough. We did a lot of work in those three days.

I think [the soundtrack for] Paris, Texas took three days, too, because that’s all the time [director] Wim Wenders had. That’s another example where you do what you can. I liked the idea. It’s easy if your musicians are really good — like jazz players used to make an album in a day or two or three. That’s no problem for them. Great players if they have an open form, can sit down and just go. When you start organizing things, then you go for a different thing and you might look for a different terrain, a different shape.

The Chávez Ravine project had to get done in its own time; that is all I can say. At one year, I thought I was done; I was certain I was done. Then by the end of the second year, I said, “Well, now I’m done, but it’s a different record now.” But then I decided, “No, I don’t feel right. I like it, but I don’t love it, so I’m not done yet.” You just have to be open to these things. And have enough money to pay for it. Christ, it’s expensive!

There is really magic to that kind of limitation in a way sometimes.

Absolutely! Especially if you have good, instinctive people who respond and just go.

This is off the subject, but what records readily come to mind as being pivotal for you?

Those Folkways collections were great. When I was a kid, it was hard to get that stuff. The only reason I heard blues was because I knew older people who were collectors and had records. When I was about 12 years old, I used to sit there every day and spend at least two hours a day playing these records and memorizing everything. That’s the world that opened up for me on record.

I remember when Sam Charters did this country/blues anthology of 15 or 16 artists on Folkways. It had an insert with photographs of the artists. At the time, I hadn’t really heard of any of these people at all. He had everybody on there: Robert Johnson, Blind Willie Johnson, Sleepy John Estes and others. He had great taste because he had good ears, and so he picked the best record of each person and laid it out for you.

There was nobody like those artists doing that kind of music in Santa Monica [Calif.]. It seemed very exotic and very verboten and full of all kinds of mystery. I just thought, “I cannot picture these people. I don’t know who they are or where they’re from or what it looks like.”

Eventually, I would meet some of these old guys. They’d sit there and say [he imitates an old blues artist], “Let me tell you boy…you do it like this.” When I wasn’t able to meet someone early on — like John Lee Hooker — I discovered that I had made up a whole scenario in my head of how he was playing and later realized I had it completely wrong!

But it got me going. I made something out of that on my own, just by misreading the whole thing. Much later, when I finally saw [Hooker] and sat with him and watched him play, I thought, “Oh, my God! It’s nothing like I thought at all. All these chords I thought I was hearing, all these moves I thought he was doing, is just my mind filling in.” So I thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” So you end up doing certain things out of some personal fantasy level.

It’s like you read a book and your mind’s eye takes some kind of ownership of that information and creates unique personalized images.

That’s right!

You were the flying saucer landing in their world.

[Laughs] Looking around and looking at things. But that’s all I did; I didn’t do anything else. I didn’t play football. I didn’t go to the movies; that’s what I did. So that’s how you learn, I guess.

Rick Clark would like to thanks MTSU’s Courtney White for her help assembling this story.