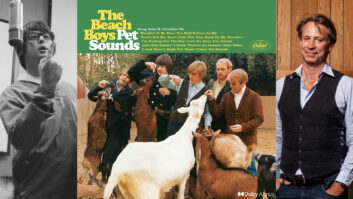

Left to right: Peter Asher, Frank Filipetti, Steve Martin, Edie Brickell

Photo: Frank Filipetti

Comedian, actor and author Steve Martin has been a dedicated banjo picker as long as he’s been in show business, but he has only occasionally elevated that interest to the top of his priority list. Perhaps you heard the Grammy-winning album he made in 2009 called The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo, or the exceptional bluegrass CD he made two years ago with the Steep Canyon Rangers, called Rare Bird Alert. The guy is serious about his music, and it turns out he’s also really good.

Since her days as a sprite fronting a loose-limbed group called New Bohemians (“What I Am” was ubiquitous in 1988 and beyond), Edie Brickell has had a fairly low-key career as a solo artist (her 2003 album Volcano is my favorite) and collaborator with various interesting folks, and also raised three children with husband Paul Simon. She has always been a terrifically appealing and engaging singer and songwriter, mixing plainspoken observations and wisdom with more abstract poetic insights.

Martin and Brickell’s brilliant and affecting new album, Love Has Come for You, plays to the strengths of both while forging a sound that is completely original and unexpected. With its vivid characters, concise storytelling and mostly acoustic instrumentation (dominated by Martin’s banjo), it certainly steps into old-time folk and bluegrass territory, yet it is not so easily pigeonholed—what do we make of the elegant strings and piano, subtle electric guitar and percussion touches, the drums and dynamic jazz bass that dapple the always tasteful and imaginative musical landscape created by producer Peter Asher? In the end it feels sort of roots-moderne.

The album started on a whim—Martin approached Brickell about writing some lyrics for a banjo piece he’d written. She loved what she heard and responded by sending him not just lyrics, but a rough performance of her singing a melody inspired by the banjo part. Martin was similarly jazzed by Brickell’s work, and they fell into a routine in which he would send her banjo melodies via email and she would quickly write lyrics and a melody, record it on an iPhone or iPad, and send it back. As she noted in a promo interview, “The opening lines came out of the banjo. The mood that Steve sets is so powerful that all I had to do was trust what I heard and how it made me feel and then just start singing, and there it was. The songs were gifts from the banjo melody.”

Asher and Martin have been friends for many years, and shared their excitement about the home-brewed recordings that Martin and Brickell were passing back and forth. “I immediately started thinking of arrangement ideas for these songs,” Asher says, “and Steve and I talked in general terms about what kind of record it could be.” After Martin formally asked Asher to produce the album, they decided to start where the rough demo explorations left off—recording just banjo and voice, but together in a great studio.

These foundational sessions took place over the course of about a week at veteran engineer Frank Filipetti’s studio, The Living Room, in his house in the scenic Hudson River town of Nyack, about an hour north of Manhattan. As an early advocate of digital consoles, Filipetti had variously championed the Neve Capricorn and Euphonix System 5 boards through the years, and favored the Nuendo recording platform, but his new studio boasts an Avid ICON D-Command console and Pro Tools 10 with HDX cards. Much of the other equipment in the studio came from Filipetti’s previous recording “home”—Studio B at Legacy (formerly Right Track) in New York City.

Brickell, Martin and Asher in The Living Room.

Photo: Frank Filipetti

“I think Peter was a little surprised when he got here, because he assumed I had a separate control room and studio,” Filipetti says, “but it’s all in one large area, with a two-story wood-beam A-frame ceiling, stone walls, a fireplace and some furniture. It was built in 1890, and it’s really one of the best-sounding rooms I’ve ever been in. The house is on a couple of acres, with lots of trees, a reservoir—we’re out in the country and it’s a wonderful place to record.

“Steve was in here in the control room area with Peter and me, playing banjo, and in the study right off this room, we had Edie singing to the track live. I had three mics on Steve—two on his banjo and one in the room.” Filipetti used an Audio-Technica AT4080 ribbon “slightly above the banjo, picking up the resonance of the head, and a B&K 4006—which are now called DPAs—nearer to the strings.” The room mic was a Sanken CO-100K. For a banjo mic pre he used a Neve 1064.

Brickell’s vocal chain mostly consisted of a new Telefunken 251 into a Neve 1064 or 1084 pre, “probably going through an LA-2A or a Summit compressor, very, very lightly touched,” Filipetti says.

As for the flow of the sessions, Filipetti says, “We did multiple performances of the songs. There was no click—Steve would provide a tempo and then we’d do a few takes—two or three tracks a day; just run through them and do them until Steve was happy with what we got. Then in the evening, Peter and I would sit here and edit the takes together. But Edie’s vocals were so spectacular you just didn’t want to lose certain lines, and usually we didn’t do more than two or three takes on her.”

Armed with what he calls “perfect vocal and banjo takes,” Asher then went to L.A. for the overdub sessions, which were mostly engineered by Nathaniel Kunkel at Village Recorder and East West. Asher “cast” each song and brought in the players as needed. “I’d say, ‘Okay, we need a keyboard player for one day, I need a straightforward bass player for one day, I need Esperanza Spalding for one evening.’ I had very specific ideas for the role each overdub was supposed to play.” Other notable musicians included guitarist Waddy Wachtel, keyboardist Matt Rollings, bassist Ian Walker and the singing Webb Sisters. Asher also played many different parts.

A couple of tracks featuring the Steep Canyon Rangers were cut at Kung Fu Bakery in Portland, Ore. with Bob Stark engineering, and Andrew Dudman handled some string recording at Abbey Road. Kunkel mixed the album in the Village’s Studio F “entirely in the box on their ICON,” he says. “I relied heavily on my UAD-2 cards—all the reverbs and effects were from that. I also used the Massenburg Design Works equalizer pretty heavily, and I’ve been using a dynamic parametric equalizer made by Wholegrain Digital; that one’s a game-changer.

“It was surprisingly easy when it came time to mix it. Frank’s recordings were stellar, and because Peter’s arrangements were correctly done, there weren’t a lot of extra parts to deal with in the mix. It was very straightforward.

“We sent the mixes to Steve and Edie. I would do live streams for her, and there were some mix-approval sessions where Steve came to the studio and I would stream to Edie, and we’d be on a conference call and we would work through issues they had, and they would talk together about where the mix was going. So they were very involved all the way through, as was Peter. It was a real collaboration at every stage.”

ONLINE EXTRA: EXTENDED INTERVIEW WITH ASHER, FILIPETTI AND KUNKEL

On the origins of the project.

Asher: “I was having dinner with Steve and his wife at his apartment in New York, and he played me some of the banjo pieces he’d been writing. A few were ones I’d heard before, but he explained to me that he was also going back and forth with Edie and she’d come up with some ideas to turn them into full-fledged songs. He played me a couple and I loved them. I left to go back to L.A., and by the time I landed I had an email from Steve, who is famous for his relatively terse emails, which said: ‘Do you want to produce the record?’ I said ‘Yes, yes, yes!’ That was the verbatim exchange.

“The idea was not to make it a bluegrass record, though there are a lot of bluegrass instruments on there, and I wanted to use the Steep Canyon Rangers, who are fantastic, on some tracks. But I also said, ‘I’d put a piano here,’ and I had the idea of using Esperanza Spalding because I had worked with her recently and was in love with her playing. I wondered, ‘What would a great jazz bass player do with this? What would someone used to playing a harmonically adventurous part come up with?’ I also had ideas for electric guitars and even some of the electronic percussion stuff that’s hidden away in there somewhere.

“I had never met Edie before, even though I know her husband [Paul Simon]. She is so amazing. She is clearly a singer of the super high quality that I’ve been fortunate to work with a lot, whether it’s Linda [Ronstadt] or Bonnie [Raitt] or Natalie Merchant, or Diana Ross or Cher, for that matter. I’ve always loved singers where you know exactly who it is the minute they open their mouth. It was a pleasure hearing every take come out of the loudspeaker; it was that good. And more than just being a great singer, she came up with these incredible ideas for melodies and words that fit over Steve’s not-obviously-easy banjo ideas. She writes sort of conversationally, but also artistically and elegantly; it doesn’t feel like it’s been slaved over.

“I was already really familiar with Steve’s banjo playing and have played with him a lot—many a musical evening would end up with him playing banjo and me playing guitar. I remember Steve and [fellow comedian] Billy Connolly both on banjos and a couple of us acoustic guitar players trying to keep up with them.”

On the banjo-voice sessions at Filipetti’s studio.

Filipetti: Steve was amazing. I’ve worked with a lot of artists over the year and he is as dedicated as anyone I’ve ever seen. He would walk in every morning, unpack his banjo and say, ‘Let’s go!’ We’d have lunch and we’d talk, we’d have our dinner and talk, but basically he was so into the music, it was incredible to watch. He was totally focused and professional, with concentration you would not believe.

“It was an absolute joy having them here. They’re just lovely, lovely people. Steve has an amazing dry sense of humor and Edie was the sweetest person in the world to work with. And that voice, once it came over the monitors, was so incredible. I was really blown away by her. One day Edie brought in some fried chicken, another day she brought in cookies. I think everyone felt really at home here. We all had a ball.

Filipetti on his choice of the Avid Icon D-Command console.

“My first digital console was a Neve Capricorn, which was just a beautiful console and way, way ahead of its time. It did have some stability issues, no question about it, but sonically, operationally and ergonomically it was phenomenal. What I liked about the [Euphonix] System 5 when I purchased that later was that it had a similar mode of thinking and operation [to the Capricorn], and what I like about the D-Command is it also has that similar mode of operation—the ability to spill faders and do everything from the center position without having to move. That’s especially important in an environment like this—the home studio. It just simplified my life greatly. I can spill out individual groups—like 12 or 16 tracks or drums, or the guitars or the keyboard group—and feel like I’m never running out of space. I can do my entire mix with just 24 faders in front of me.”

On plugs-ins vs. outboard.

Filipetti: “My philosophy is once you go digital you never go back. The conversion is the weak link—not that it’s that weak anymore, the converters are fantastic. But whenever you take one kind of energy and turn it into something else, no matter what the transducer is, that’s the hardest part: acoustic to electric, analog to digital. So once I am digital I never go back.

“For mixing I use plug-ins, but if I want an LA-2A on it, then I’ll put it on at the front end, before it goes to the A-to-D. I’ll put on the Neve or Chandler or the Tube Tech mic pre or whatever. But once I’m in Pro Tools I never leave the box again. When I’m mixing, I use a lot of the UAD plug-ins inside the box, and that’s worked great for me. And sometimes those LA-2As and 1176s in the box sound better to me than the [hardware] units I have here. I know some people are going to disagree with that, but I find the whole issue of tools to be silly—you have to do it this way or that way. I have my way of doing things. I can’t get into this thing where you have to get this analog sound, or you can’t go in the box or you have to go in the box. It drives me crazy. It’s not the gear, it’s the people doing the gear. I was working on the best equipment in the world for 15 years as an engineer and I got my first Grammy working on an OTR in somebody’s house. [Laughs.]

On the overdub sessions at the Village Recorder.

Kunkel: “I’ve installed a lot of my equipment in the Icon room at the Village because I work there so much. I’ve got my GMLs, I’ve got my Lynx Aurora converters, my TC Electronics System 6000 and my JBL LSR6300 [monitor] setup, as well as my ATC speakers—I go back and forth between the two.

“Just about everything that wasn’t the banjo and the vocal were thought up by Peter, and we spent our time doing overdubs around the banjo and voice tracks they had already cut. It was a great way to do it because you had a vibe for what the song was going to be and you knew how it was going to work and how everything was going to fit together. There was already a real texture to the track.

“We did a legitimate track date where we had bass and drums and piano, so the songs that would benefit from having a rhythm section play behind them would have that. And then there were other songs that were such sparse arrangements to begin with that we could just do one or two players at a time. Peter played a lot of things as well.”