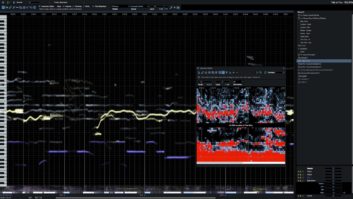

Mixbus features many extras, including user-defined shortcuts, EQ on each channel and control surface support.

Thanks to efforts from many major plug-in manufacturers, modeling has become a very accessible way to employ the signature sounds of popular mixing consoles in DAW-based working environments. We’ve seen quite a few offerings that represent the channel strips of different analog consoles, but up until now, a virtual Harrison has existed solely in Universal Audio’s UAD platform in the form of a modeled EQ based on Bruce Swedien’s hit-making Harrison 32C.

According to Harrison, the sound of its consoles runs deeper than a simple EQ or compressor. The company found that running a plug-in version of its channel strip through the summing architecture exhibited in the aux buses and the main summing bus of most DAWs results in a sound that is unsatisfactory. Rather than building a DAW from the ground up, it seemed a better idea to take an existing infrastructure and swap out portions with newly redesigned components. Harrison chose the Ardour workstation (www.ardour.org), which was cross-platform (Mac/PC/Linux), had a large existing user base and offered the ability to modify the programming. Harrison had an existing relationship with Ardour, which helped design the software side of Harrison’s Xdubber unit. This relationship was advanced through the development of Mixbus. Harrison’s engineers took the foundation of this software, but made some serious changes.

Old Meets New

On launching Mixbus, an Ardour user will first notice a complete redesign of the Mix window. This change affects both the overall appearance and the functionality. The mixer reflects each of the tracks in the Edit window with a full channel strip, complete with a panner, HPF, 3-band semi-parametric EQ, compressor/limiter and four Mixbus assigns. Each of these components can be switched in or out, allowing easy A/B comparisons. This differs from the plug-in workflow in the DAW world, which prompts you to instantiate a plug-in for every effect/processor needed. Mixbus allows access to more advanced features — such as an input trim and automation-enable controls — via a small button at the bottom of the channel strip that reveals a large window with a range of options.

The console vibe continues from there with a pre-routed signal flow. Each mixer channel can selectively feed any, or all four, of the Mixbuses. The output to the master bus is also switchable, so a signal can feed the master, or not, while still feeding any of the auxes. Each Mixbus features simplified tone controls, panning, a compressor/limiter and a “tape saturation” control. This tape saturation serves as an overdrive function and can get pretty crunchy if cranked. The master bus has the same controls as the Mixbuses — minus panning — but adds a look-ahead limiter and K-Metering (engineer Bob Katz’s system focusing on averaging signal at 0dB VU while allowing 14 dB of headroom). Last, the track-based channel strips, Mixbus channel strips and the master channel all feature both pre-fader and post-fader insert points.

But How Does It Sound?

The sound of the EQ section in the channel strip is very clean. They are not as warm as a typical analog EQ or a corresponding software model, focusing on precise carving of frequencies rather than on imparting a good deal of color. Given its convenience and clean sound, however, I found little reason to turn to plug-ins and instead relied on Harrison’s EQs for the bulk of a music mix. The high and low bands are shelving, while the central Bell filter emulates Harrison’s 32 Series console, with a Q that tightens up with increasing boost/cut. The compressor on the channels and summing buses leaves little to complain about. It has three selectable modes: Leveler, Compressor or Limiter. These modes inorporate the ratio and time constraints to match common hardware types. Threshold and attack-time controls are both available through the channel strip; makeup gain is only accessible through the automation-enable page.

I analyzed the compressor’s behavior on a picked acoustic bass. In the original source material, the high-midrange pick attack was relatively even throughout the performance while the lows jumped around in level, particularly during slides and hammer-ons. With a few quick tweaks, the compressor drew out a good amount of harmonic content, thoroughly enriching the midrange surrounding the attack. I was impressed with the way it leveled out the chaotic lows without causing noticeable pumping in the upper-mids. I tried several other software compressors on the same source without such pleasing results. There must be a well-structured detector “circuit” and an intelligent auto-release.

The real feather in Mixbus’ cap, however, is its summing algorithm, which exceeds expectations. All of the buses feel like they have generous headroom. You can combine a good amount of signal through them and still maintain a warm, meaty low/low-midrange without muddying the upper range. This could be attributed to the 32-bit floating-point operation — or just well-written code. Relative to Pro Tools or Logic, I would consider it a much cleaner sound, more akin to Nuendo, or even a hardware console. Another nice touch is delay compensation for each of the Mixbuses. Whether you’re using them as effect returns for your time-based processors or for parallel compression, you’ll get phase-accurate processing. This is attempted by other software, but rarely executed with such ease as I found with Mixbus — especially at this price point.

In the End

The mixer side of the Harrison Mixbus 1.1 software is quite impressive. There are also such niceties as user-defined keyboard shortcuts, a time-scale including timecode and incorporation of control surface support. That aside, the entire operation relies on a freeware internal busing structure called “Jack,” which leads to some frustration and confusion until you get the hang of it. Also, the editing side of Mixbus leaves something to be desired, and the operation of the software was not without glitches. To that end, I don’t think this is the DAW to replace all DAWs. I could, however, easily find myself editing in Pro Tools, exporting all of the edited tracks as audio files or stems, and bringing them into Mixbus just for the mix. When using the software exclusively for mixing, it was admirably smooth in operation and offered a sound superior to Pro Tools. I have always been a fan of mixing in Nuendo with its pre-configured EQs and clean summing, but that software’s price tag of $1,799 makes it rather exclusive. I would certainly recommend Mixbus as a very affordable alternative to conventional in-the-box mixing, with a sound on par with a hardware summing bus or high-end mixing software.

Brandon Hickey is a recording engineer and post-production consultant.

Click on the Product Summary image to view the product page