David Bowie, ever the visionary, made a smart move back in 1997, partnering with an investment firm to raise cash from his intellectual property—his catalog of songs—through Bowie Bonds. Ten years later, it became apparent that Bowie had made out like a bandit just as the record business was beginning to crash.

Fast-forward through the new millennium and there has been a Gold Rush over the past few years, as artists from The Beach Boys and The Killers to Genesis and Massive Attack—as well as Bowie’s estate—have cashed out their recording catalogs with a handful of investment firms.

Deal details are rarely disclosed, but some of the reported numbers are eye-popping: Bob Dylan, for instance, may have reaped upward of $600 million for his publishing and masters, while Bruce Springsteen is believed to have received $500 million for his songs and recordings.

For artists, these arrangements offer certain tax advantages while potentially relieving financial pressure for the rest of their lives and, for older musicians, enabling them to plan their estates. As for the catalog aggregators, they are banking on a healthy return on their investments through sync licensing for film, TV and commercials, record reissues, merchandising, and the like. But to realize any sort of return on their investments, the recordings, some of which may be many decades old, need to be in a playable condition.

Kelly Pribble, director of media recovery technology at Iron Mountain Entertainment Services, has a simple motto: “It’s only rock ‘n’ roll if you can play it.” IMES, which has three digital studios in the U.S. and two in Europe, offers secure physical and digital asset preservation and archiving services for the wider entertainment industry, not just the music business. Pribble, for his part, spends much of his time working with rights holders—whether that’s an artist or one of the new wave of investment companies—to help evaluate, organize and remediate their legacy music recordings, often also setting up a plan to migrate them as storage formats evolve.

Wait, hit the Pause button. Remediate?

DO NO HARM

Remediation is the act of stopping and even reversing harm caused by environmental factors. For music catalogs, there can be a host of such factors, from recordings being fixed in an obsolete format to damage due to storage issues to problems with any associated information— the metadata. It’s the work of Pribble and his IMES team to remediate those issues before archiving assets and their metadata for clients.

Even if they have been previously archived, decades-old original assets can only benefit from being transferred again using the latest technology. Currently, Pribble captures analog audio assets through Prism Sound ADA-8XR converters at 192 kHz, 24 bits.

View from the Top: Lance Podell, Iron Mountain

“I use those Prism units because I just love them,” he says. “They don’t color the sound. As an archivist, I don’t want to color what’s on the tape when I make a digital file. If it’s digital, I go bit-for-bit so there’s no loss.”

Over the years, Pribble has seen it all (but due to strict confidentiality agreements is unable to name all but a few IMES clients). Issues with age-old tapes occur almost daily in his job. “They’re just so fragile. Any manipulation—sometimes even putting them on a machine and rewinding them in a very slow mode—and the tape just breaks,” he says.

One remediation project involved an archive of some of the oldest tapes he’s ever handled. “There were all these challenges that I hadn’t really seen that much because most of the time we don’t deal with 70-year-old tapes.”

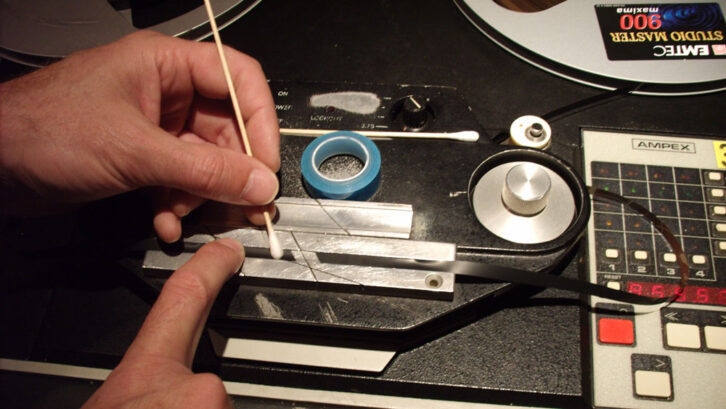

Many of the splices between paper leader and tape, not just at the head and tail but between songs on album masters, proved challenging, with adhesive from the tape breaking down and oozing between layers. Pribble had to carefully peel everything apart without removing any oxide.

“The downbeat is right at that splice, and if one little bit is missing, you’re going to have a dropout,” he explains, noting that adhesive at the splices had also bound layers together. “As I was getting closer in a very slow rewind mode, I would stop and hand-wind to that point or I could damage the song.”

STICKY SHED AND ADHESION

You may be familiar with sticky-shed syndrome, which causes the magnetized coating on certain tapes to separate from the backing due to the deterioration of the binder—the glue—holding them together. At a Recording Academy presentation in late 2020, Pribble called attention to a new issue, which he called adhesion syndrome, which had affected the album masters of Bob Dylan’s Empire Burlesque, from 1985, and 1986’s Knocked Out Loaded. The records are part of a collection of more than 100,000 items—hours of audio and video, manuscripts, notebooks, photos and other assets—acquired by the George Kaiser Family Foundation and the University of Tulsa, some of them now on view at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla.

Pribble reported that the issue was first observed 10 years previously in South America (tape manufacturing formulations can vary by region) but had become a recent phenomenon in the U.S. “The edges are bound together, and as you unwind the tape, it rips the tape,” Pribble explained at the time. The condition can pull the oxide from the backing, creating pinholes.

“Altogether, there were 63 two-inch masters from Bob’s two records that we were able to safely unbind and transfer successfully,” he continued. “I didn’t have to do much once we were unbound and transferred; the audio was pretty good.”

SAVE YOUR DATA

These days, we think of metadata as information embedded with a digital audio file. For analog material, that metadata is typically the writing on the tape box. But if it’s missing and the producer, engineer or artist is no longer around, identifying a song, much less which take is which, may be problematic.

On one recent project, Pribble was rewinding a tape from a box with scant information on it when he caught something out of the corner of his eye. “Somebody at some point decided to write the name of the song and the artist on the leader tape. That was just so cool,” he says.

With no notes it might not even be obvious how many tracks are on a half-inch multitrack tape, Pribble says, and it doesn’t necessarily help to play it. For instance, a 3-track tape will play on a 4-track machine, and vice versa—just not correctly for archiving purposes. Happily, there’s a tool for that. “We have a magnetic viewer,” he says, noting that it makes the tracks visible.

That said, previous archivists may have done a thorough job. Pribble reports seeing tape boxes noting defective tracks with directions to use a copy or even an alternate take from elsewhere in the collection, including for some very familiar rock ‘n’ roll classics.

“If we didn’t have this information, we might have used these versions and said, ‘This is not a great version.’ And we may have not known where the other good versions were or where to go look for them,” he says. An outtakes reel may include alternate takes that are practically indistinguishable from the familiar—but now unplayable—released master, which can save the day when a collection is reissued decades later.

WORKING MACHINES

As for obsolete recording formats, devices such as Sony’s PCM-1630 have since become difficult to source, but IMES saw the writing on the wall and has long since amassed a collection of vintage playback devices, analog and digital. Yet there can still be challenges even when a working playback machine exists.

Spotify requires tracks to be at a minimum 96 kHz sample rate. What if a project was archived to DAT? “DATs are at 44.1 or 48k,” Pribble points out. “As we archive today, DAT is probably one of the worst formats to have your storage on.”

On one recent reissue project, there was an issue with a master that he had only previously encountered with very old acetate tapes, where it starts to shrink as it breaks down and begins to curl within the reel as it unspools. When he played the tape, it would move in and out of contact with the head stack, he says: “I call it dancing. How do we fix that?”

Pribble, a former studio builder and owner who holds a U.S. patent for a method to remediate magnetic tape, is not one to shrink from a technical challenge. “It literally took us four or five days to come up with a fix. I’m an inventor; I never give up,” and neither does his IMES team, he says. In the end, a device made from a piece of foam and some medical tape held the tape against the head just enough, without affecting the speed, to make an archive copy.

“We think we’ve seen most of the problems until we see something like this, and then it’s a new challenge,” he says. “I love challenges, and my team loves the challenge, but we were able to fix it. I’m so very pleased and proud of them.”