Recently, a fledgling twenty-something composer named Darren visited an old-folks home outside of New York City to talk to a man we’ll call Grandpa, a long-retired composer of music for TV commercials. Darren was hoping to gain some insights to help build his career. Through one of our many sources, Mix was able to obtain a recording of their conversation:

Darren: Hello, sir. I’d love to pick your brain about the commercial composing business. I did a Google search, and you came up as a good source of info.

Grandpa: Google, eh. Listen, kid, when I was composing for commercials, we didn’t have any of that fancy computer stuff.

Darren: No computers? How did you write music?

Grandpa: I would sit in front of a piano with a pad of score paper and a metronome, watching a ¾-inch video of the spot or scene.

Darren: What’s a ¾-inch video?

Grandpa: It was this big, clunky and expensive video-cassette format that was standard in the back then.

Darren: How did you figure out your timings?

Grandpa: With a stopwatch and a click book.

Darren: A click book?

Grandpa: It was this really fat book that had every possible BPM and duration in list form, and you could use it to figure out the right tempo for making hit points.

Read more Mix Blog Studio: Cool Plug-ins From the Land of the Euro

Darren: Sounds so archaic. After you figured out your tempos, what did you do next?

Grandpa: Then I’d write out my melody and the chords and send it to the arranger.

Darren: The arranger? Is that a piece of software? I thought you said you didn’t have computers back then.

Grandpa: We didn’t. An arranger is a person who writes arrangements for the musicians.

Darren: You brought in real musicians?

Grandpa: All the time. A drummer, a bassist, a couple of guitar players; horns, strings.

Darren: Crazy. How did they all fit in your home studio?

Grandpa: Actually, we recorded in commercial studios.

Darren: You’re kidding. How could you afford that?

Grandpa: Believe it or not, back then there was something called a “budget.” What’s more, we were all in the musicians’ union, and everyone who played got on a union contract for every spot that went final. Then, if the commercial stayed on the air more than three months or the music got re-used, we’d get residuals.

Darren: Re-what-tuals?

Grandpa: Residuals. Re-sid-uals. Residual payments.

Darren: No way!

Grandpa: Way. If you were working in New York or L.A., it was almost always through the union. There were almost no buyouts, except for the occasional local car dealer commercial.

Darren: Wow. I thought the musicians union was only for wedding bands and Hollywood scoring sessions. Dang. I only make money if the music I write gets used in a commercial, and then I get a one-time payment, and that’s it. And it’s so hard to win because I’m always up against at least 20 or 30 other versions. And even the few times I have won, the agency people put me through hell.

Grandpa: If it makes you feel any better, agency people were idiots back in my day, too. I must say, it’s a shame that you don’t get paid for doing demos.

Darren: I never knew anyone did.

Grandpa: When I wrote a demo as a freelancer for a music house, I would always get a demo fee, even if my version wasn’t chosen.

Darren: Amazing!

Grandpa: You’re darned tootin’ it was amazing. Back then, if you could get a staff gig at one of the big music houses, you could do really well. I was on staff at [unintelligible] for 11 years and then opened up my own company. Residuals up the wazoo!

Darren: That was the name of the company?

Grandpa: No, I mean we made a lot of residuals. Back then, almost every commercial was a jingle and had a group of singers on it. The singers were in SAG or AFTRA, rather than the musicians union, and got paid much better. Back then, singers who were busy made millions. They all drove nice cars and had fancy houses in the country.

Darren: You’re kidding, right?

Grandpa: Nope! We composers could often join in the vocal group so we could get that SAG or AFTRA money, too. Sometimes when we didn’t even sing we’d still be listed on the contract as being part of the group—and those vocal-contract residuals helped me get my daughter through college. I’ll tell you! And when I had my own company, and me or one of my writers wrote the winning version, I’d get paid a hefty creative fee. It could be as high as 20 grand for a national spot.

Darren: [Unintelligible gurgling noises]

Grandpa: Are you okay, kid?

Darren: Yeah. Yeah. Actually, commercials are just a stepping stone for me. I’m aiming to become a film-music composer.

Grandpa: Is that so?

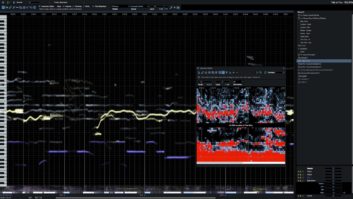

Darren: Yup! I just finished scoring a full-length documentary on pig-farming in Argentina. I sampled real pig sounds, turned the recordings into loops and triggered them in Ableton.

Grandpa: Pig farming, eh? How much did you get paid?

Darren: Well, the producer said they don’t have any money for music, but the exposure is going to be amazing. A few more of these and I can move out of my parents’ basement. Hollywood, here I come! And check this out: a friend of a friend of a friend of a friend knows Hans Zimmer. Contacts are everything, you know.

Grandpa: Look, kid. It’s been nice talking to you, but bingo starts in five minutes; I’ve got to go. Good luck.