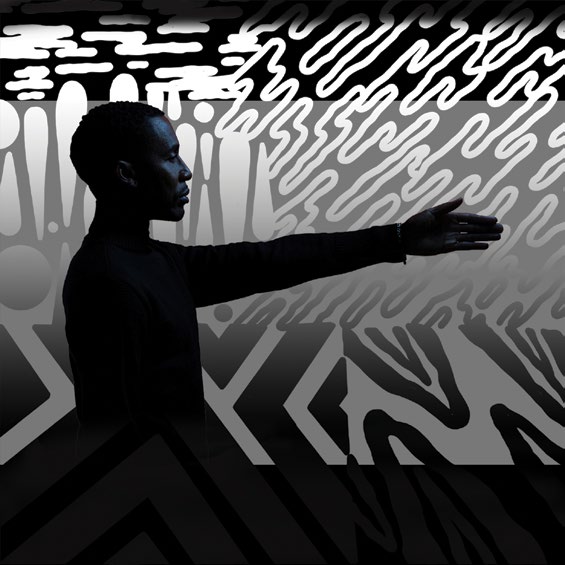

On the day Raphael Saadiq’s latest album, Jimmy Lee, was released, he played a hometown show in Los Angeles where he performed the entire album in running order. “I always wanted to see if I could pull off having people listen to an album all the way through, the first time out,” says Saadiq the following week at his North Hollywood studio, Blakeslee Recording Co.—a high-ceilinged, high-quality space on par with the professional ones he would get booked into as one-third of Tony! Toni! Toné!

Jimmy Lee is an album with a story that needs to be heard from start to finish. Like much of Saadiq’s work, it is a concept album of sorts. This is never his intention. In fact, he didn’t realize there was any kind of theme on the self-produced Jimmy Lee until he started promoting the album and had to respond to what listeners were taking away from it. The album is named for and, in large part, about, Saadiq’s older brother, whom he lost to addiction many years ago. Jimmy Lee is one of four of Saadiq’s deceased siblings. He wrote Jimmy Lee as a way to speak up for his brother.

“Thinking about my brother self-destructing, once I had the vision, I started coming up with more songs with that vision,” Saadiq says. “I have friends who have dealt with drugs. I’ve been around it myself a little bit, even though I never got into it. Everybody is hooked on something. I go to Kaiser with my mom and it looks like New Jack City. Where you pick up your meds is huge. It’s like a Home Depot. Everybody in there is like a zombie for pills. I felt I knew how to talk about this.”

Musically, Saadiq refers to Jimmy Lee as not so much of a time but of a space. Spaces he has occupied in his 53 years, specifically referencing the MTV heyday of Duran Duran, Tears for Fears and David Bowie in the early to mid-‘80s, with an emphasis on synthesizers and synthesizer-generated strings. Saadiq’s music is known for going backwards referentially, as much as he pushes forward. The drums are the futuristic element on Jimmy Lee, aided, in part, by his forays into Ableton.

Three years ago, Saadiq started using Ableton as a writing tool. His recordings are still to Pro Tools with the help of his primary engineer, Hotae Alexander Jang, but Ableton is the first interface Saadiq has used entirely on his own and the only studio piece he has ever taken home or used to make music in other locations. He might have started drums in Ableton, or he might have had hi-hats come from a drum machine, or put the snare back into Ableton after recording it live with a drummer. Drawing from the endless wall of drums Saadiq has at Blakeslee, he plays drums himself on four songs, including “Rear View” and “Belongs to God.”

It is the bass, however, that is Saadiq’s first and primary instrument. The Fender 1962 Precision is his go-to piece, which, interestingly for a bass playing producer, is quite muted on Jimmy Lee. Playing with flat-wound strings for a deader sound—which Saadiq sometimes mutes even further with his hands—that doesn’t mean the bass isn’t doing a variety of clever things, most of them percussive.

“The bass is the other side of my voice,” Saadiq says. “I believe in my singing, but for many years, it’s been about protecting my voice with the bass, meaning if I falter in my vocals, the bass will take care of me. It’s my voice, too.

“I’m a simple bass player,” he continues, “I don’t have a lot of soloing in me. I don’t play a five-string. I play a lot of syncopated basslines, a lot of rhythmic basslines. Some of the songs don’t even have a bass, but there is a bass note in the chords. I see it as the instrument that pulls all my production together. It makes everything better.”

Even with his affinity for the instrument, Saadiq hands the bass duties to whomever he feels is the best fit for the song. One of the more prominent basslines on Jimmy Lee is on “Glory to the Veins,” where the instrument illustrates the story of the song moreso than any other sound. It is played by Saadiq’s partner, Charles Brungardt, who originally wrote it for a videogame the two were producing for their videogame production company, IllFonic

Saadiq didn’t have the patience to wait for a choir to sing the vocals on “Riker’s Island” so he sang them himself. He sang the chorus over and over—in tenor, soprano and alto—taking on different characters each time. He then multiplied those recordings for the full and rich vocals heard on that song.

Saadiq tends to record his vocals in isolation, without an engineer, going through an original Neve 20173 compressor. The Neve is one of the many vintage outboard pieces of gear that he has amassed the past 15 years and incorporated into Blakeslee, which also houses a jukebox-looking, immaculately kept Studer tape machine, a classic DAT player and three SSL desks in three different rooms.

“I use the Shure SM7B almost 90 percent of the time,” says Saadiq. “You can get really close and personal with an SM7B. I’m a tenor, and sometimes my voice is too bright. It has developed some warmth around it over time, but I’ll use the U 87 for a different bite. There is a lot of slapback and reverb in my vocals. My thing is to play with effects to distort my voice and do some wacky stuff. I’m not trying to win a singing contest. I just wanted the album to come from my perspective. I really wanted to tell whatever story I had on any particular day, or whatever story I knew from a long time that I could tell today.”

Part of Saadiq telling these stories is the sound effects, a doorbell indicating a drug dealer coming to the house, for example. There are pre-introductions, an interlude and a redux heard in between the almost jarringly abrupt, but very much intentional endings to each song. Saadiq attributes these quick switches to watching Adult Swim cartoons and a vehicle for shuffling through musical palettes and mindset channels.

“Everybody has a Jimmy Lee in their life,” he says. “The album is opening up different wounds for different people. Starting a chapter and maybe closing a chapter for others. At this point, Jimmy Lee has taken on a role that I don’t feel has anything to do with me.”