How do you define audio fidelity? Is it the signal-to-noise ratio, the frequency response, the distortion? Is it the number of channels, bits or samples marching by per microsecond? Or do you perhaps take a different approach and define fidelity more subjectively, as the ability to re-create an aural experience-to stimulate thoughts and emotions that cause the listener to be transported, completely and faithfully (for such is the origin of the word), to another time and place?

In our business, we sometimes pay so much attention to the numbers and formulas of the former, that we forget about the latter, figuring that if we do the tech stuff right, the emotional stuff will take care of itself. But sometimes one can have a transcendentally high-fidelity experience, despite a signal chain that is decidedly low-tech.

In the past few months, as it happens, I’ve had two of these. They have brought together many of the things I have loved and worked with-radio, recording, avant-garde concert music, the Internet, writing and storytelling-and that’s a big reason why they were so meaningful. The technology and the delivery systems, while certainly useful, were decidedly minor players.

For the past two years, as I’ve been telling anyone who will listen, I’ve been doing a very exciting project with G. Schirmer, the music publisher. Schirmer recently acquired the rights to a historically significant piece of music that exemplifies the word “outrageous”: the Ballet Mecanique, by George Antheil. Although the piece was written in 1924, until recently it had never been performed in its original version. That’s because the score calls for-besides seven percussionists, two pianists, seven electric bells, a siren and three airplane propellers-16 synchronized player pianos. Antheil, who lived in Paris at the time but was actually from Trenton, N.J., thought he was composing something playable, but he was wrong: The technology for synching up two player pianos, to say nothing of 16, simply did not exist.

So he rewrote the piece several times, first in 1926, replacing all but one of the player pianos with pianists, and then in 1952, getting rid of even the last one. The 1952 version is performed fairly frequently, and I first encountered it as a teenager when a percussion teacher at a music camp gave me a tape of it. Listening to it was a great thrill, especially the airplane propellers. From an early age, I loved uncategorizable modern music, the noisier the better, and for many years, I hoped that I would someday have the privilege of hearing this extravaganza performed live.

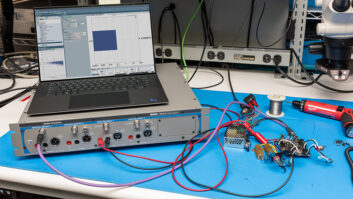

So you can imagine my delight when Schirmer asked me to take Antheil’s original 1924 score-which I never knew existed-and translate it into a MIDI sequence. This could then control a stage full of modern MIDI-equipped player pianos, like Yamaha Disklaviers, which meant that this extraordinary piece, 75 years after its composition, could finally be performed as the composer originally intended. I jumped into the assignment with both feet, not only doing the sequencing, but also obtaining samples of all the noisemakers, building a MIDI-controlled electric bell array and even arranging last November for a performance of the piece at the school where I was teaching. The local NPR station, WGBH-FM, set up a live Webcast of the concert, and companies like Apogee, Tascam, Shure, Millennia, Redco, Kurzweil, EAW and MIDI Solutions all pitched in with equipment donations so we could pull this off. Most importantly, Yamaha lent us 16 Disklaviers. The concert was a screaming, crashing success, and Yamaha is now trying to get the thing into the Guinness Book of World Records.

If you’re interested in the technical aspects of this project, I’ll be detailing them in an upcoming issue of Electronic Musician. You can also find more at a Web site I’ve put together, www.antheil.org. For now, suffice to say that working on the Ballet Mecanique has been the most fun, over the longest period of time, I can ever remember having.

One of the best aspects of the project has been the dozens of people who have discovered what I’m doing and have assailed me with questions, ideas and contributions. Truman Rex Fisher, a retired music professor in Los Angeles, offered an incredible gift: Antheil’s voice. Antheil died of a heart attack in 1959, and there are no films or videos of him available. But Fisher had recorded an interview with the composer just a year before his death for a radio station in Pasadena, and he was eager to send me a copy. So it was just a couple of weeks before the concert and after spending a year and a half studying this man and his work in microscopic detail, I finally knew what George Antheil sounded like. Between the tape hiss, vinyl noise, dropouts and random dips in level, there was magic in this recording, and I felt a delightful chill as I listened to the tape for the first time in my studio.

The magic was there for many others, too. Antheil was a great storyteller-his autobiography was called Bad Boy of Music-and this interview was no exception. I played a piece of it for the concert audience, in which he describes being, at age 3, so bitterly disappointed at receiving a toy piano for Christmas, instead of a real one, that he took it down to the basement and chopped it up with a hatchet. They fell out of their chairs laughing.

But there was more, even higher fidelity, yet to come. Flash once again back to the ’60s: Not long after I became a Ballet Mecanique fan, I found, in a totally unexpected place, another Antheil devotee: a writer and storyteller whom many credit with the invention of talk radio-Jean Shepherd.

Shepherd plied his trade late at night on WOR, a clear-channel AM station out of New York. For 45 minutes every weeknight (plus a 90-minute Saturday show live from a nightclub in Greenwich Village, which I dragged my parents to twice), Shepherd would hold forth on the trials and tribulations of growing up in the Midwest during the Depression, regaling his invisible audience with tales of disastrous first dates, disillusioning visits to Santa Claus, renegade fireworks and drum majors taking their revenge on a small town on the Fourth of July, kids double-dog-daring each other to lick frozen light poles and other milestones of “kid-hood.”

Kid stories were not his only stock in trade; he also told stories of his Army days, and often he would spend a show expounding, usually with a great deal of irony and sarcasm, on some aspect of popular culture, whether it was a sneaky new advertising campaign, a dumb TV show, the fate of the Yankees, the rise of “slob art” or just some story in the newspaper that had caught his jaundiced eye. He was a master of the put-on, one night extolling his listeners to go out the next day and ask at their local bookstore for a racy Victorian memoir that didn’t actually exist, causing booksellers all over the East Coast to rantically scramble for copies. Another night, he told them to put their radios, cranked as loud as possible, in their windows, and played the sound of a freight train guaranteed to wake the dead, or another night, he managed to convince them all to scream into the night, “Drop the tools, we’ve got you covered!” presaging by about 20 years the climactic scene in the movie Network.

But it was the stories-which occasionally appeared in Playboy, thereby increasing his coolness factor dramatically-that kept his loyal audiences, in large measure teenage boys, glued to the radios underneath their covers, knowing that this disembodied voice in the darkness was delivering them The Truth.

His lessons, as I learned them, basically boiled down to: 1. Other people have gone through what you’re going through, so relax. 2. Whenever anyone says they know what’s good for you, they have a hidden agenda and/or are trying to sell you something. 3. The secret to becoming an adult is coming to the realization that there is no secret to becoming an adult. Although he was hardly a political radical, it was important stuff for young people to be hearing in those turbulent times, and it shaped many minds of my generation to be wary of the world around them. And it was one of the most effective uses of the medium in its history.

Shep (as he was known to those who loved him) always sounded like he was winging it, improvising on the air, conversing one-on-one with an unseen presence in the studio, but he was in fact most of the time working from carefully prepared notes, if not a script. While the beginning of his show often rambled, he always hit the punchline right on the dot at 11 o’clock, when his show (and his outro, the deservedly unknown “Bahnfrei Overture” by Edouard Strauss, the least-accomplished member of the famous Viennese musical family) ended. It was a masterful performance, night after night, and if he was known only to a select audience at the time, his influence was widespread and long-lived: Garrison Keillor’s stories from Lake Wobegon owe a huge debt to Shepherd, and the long-running TV series The Wonder Years literally stole his narrative format and watered it down for prime time.

To further illustrate his stories, Shep kept on hand a highly eclectic library of music. There was ’20s jazz (which he would play along with on kazoo or Jews harp), sentimental “cheap” guitar music, dramatic film music and some amazingly avant-garde stuff, including Stockhausen’s electronic/concrete masterpiece “Gesang der Junglinge” and, in the only extant recording at the time, Antheil’s 1952 Ballet Mecanique.

By the time I first encountered the Antheil work, I had been listening to Shepherd religiously for several years, so when I heard my teacher’s recording for the first time, I thought there was something familiar about it. Sure enough, one night, while Shep was spinning one of his many tales about the hellfire of the blast furnaces in the steel mills of Indiana, this horrific industrial percussion music came up, and I almost fell out of bed. I knew what this piece was! I was probably one of the very few people in his audience who did, and I was certainly the only 14-year-old.

Flash forward to last year. As I began to put together the concert that would feature the Antheil premiere, the thought came to me that Jean Shepherd, wherever he was, would love this. Doing a Web search, I found several sites devoted to him, and one of them even gave a mailing address in Florida, taken from his amateur radio license registration (another reason why I loved him as a kid-I was a ham, too). So I wrote to him, telling him what we were doing, and invited him to come hear our revival of one of his favorite pieces. I never heard back from him, but I wasn’t surprised. The Web sites all reported that he wasn’t well and was keeping out of the public eye.

In the meantime, hidden in the back of an academic thesis on Antheil I had found gathering dust on a college library shelf, in an appendix entitled “Unpublished Recordings and Tapes,” I noticed this item: “Jean Shepherd Show, February 14, 1959, program on Antheil. Tape. Antheil Estate.” Antheil had died two days before that date-which meant Shep had eulogized him on the air! Since this was before my Shepherd days, I had no idea he had done anything like this. But now I had to hear this tape.

The executor of the Antheil estate is a San Francisco composer named Charles Amirkhanian, and when I asked him about the tape last summer, he confirmed its existence, but since he was not a New Yorker, its profound historical significance had escaped him. And unfortunately, since he was just about to leave for a year in Europe, he doubted he would be able to dig it out of the archives for me anytime soon.

And then, on October 18, exactly one month before my concert was scheduled, I woke up to see an obituary for Jean Shepherd, 78, in the morning paper. Immediately the Shepzines on the Web started posting memories and testimonials from hundreds of men and women who grew up listening to him, and their stories all contained one common thread: In their formative years, Shep’s voice was one of the few they could trust to tell them how the world really was, and they were forever grateful to him. The sense of loss, as I read these pages and pages of emotional outpourings, was palpable.

I posted a memorial page on my Antheil site, too, relating how Shep was a fan of the composer’s, and hoping that someday I would find a recording of that eulogy from 1959. A few days later I got an e-mail from one Richard Starr, from Thetford Center, Vt., a little town near the Connecticut River.

Richard grew up in Brooklyn and was an audio tinkerer at an early age. He and his father put together a “hi-fi” tuner kit from Lafayette Radio (which, he recalls, didn’t work and had to be sent back to the company to be finished), and they also had a Wollensak half-track mono tape recorder. In the late ’50s, Shep was only on Sunday nights, and that being a school night, Richard’s parents didn’t allow him to listen to the program live. But through the magic of tape recording-and he was hip enough to connect the tuner and recorder electronically, not just sticking a mic in front of the speaker-Richard could listen to Shep the next day. Of all the shows he taped, he kept only one-the Antheil eulogy.

He is now a schoolteacher, but Richard still loves to fool around with audio, and he’s done a lot of volunteer work for Vermont Public Radio. He doesn’t have a reel-to-reel deck anymore, but a few years ago, when he did, he transferred the tape of that show to cassette. Today he has a CD burner. The day before our concert, he heard a report on the Antheil project on National Public Radio’s Morning Edition, and that night, lying awake at 3 a.m., he thought to himself, “Gee, I wonder if that guy would like a copy of this tape.” So he found my Web site, saw that that was exactly what I was looking for, and contacted me. A few days later, I received in the mail a freshly minted CD containing Jean Shepherd’s 1959 eulogy for George Antheil.

The track starts out with the Ballet underneath a typically warped retelling of the fable of the ant and the grasshopper (the grasshopper is rewarded for not doing any work), and as it ends, the music rises and there’s a stifled cry from Shepherd as if he is being overwhelmed by it. A few seconds later, his voice returns, in an urgent whisper: “Isn’t that great, this music? Do you know that I know the little guy who wrote this?” The music stops, and he bends down close to the microphone, telling how he met Antheil in the Horn & Hardart cafeteria on 57th Street in Manhattan. The composer invited Shepherd up to his hotel room to show his new friend that he had just accomplished a lifelong goal-he had bought a painting by Rembrandt. Shepherd goes on with more memories and stories, in a rush of images and snippets of conversation and finally ends with, “And I never saw that little guy again.”

Richard’s CD sounds…well, just like an AM radio. There’s a little background hiss, a little modulation noise, but Shepherd’s voice comes across as clear as if I were listening to the trusty Lafayette Radio 4-band receiver (which didn’t work all that well, either) of my youth.

But before I listened to it, I put that CD aside for a few days. When the concert and the subsequent recording sessions were all behind me, my wife and I escaped for a weekend to a little Maine seaside town normally overrun with tourists but gloriously abandoned in the off-season. And so we found ourselves all alone sitting in the car at a beautiful beach at sunset, watching the waves and the dimming light, listening to Jean Shepherd, just now gone, eulogize his friend Georsge Antheil, now gone 40 years. But the crowning glory of Antheil’s youth had just been heard by several thousand pairs of fresh ears, and so that part of him lives on. Shepherd, thanks to his writings, videotape and the Web, also lives on. And I, hearing that voice, and that music, in all its lo-fi glory, found myself at once in the ’60s of my youth, and in the ’20s of Antheil’s youth-all in the closing weeks of the ’90s. And they were all, in that moment, equally real.

Now that’s what I call fidelity.