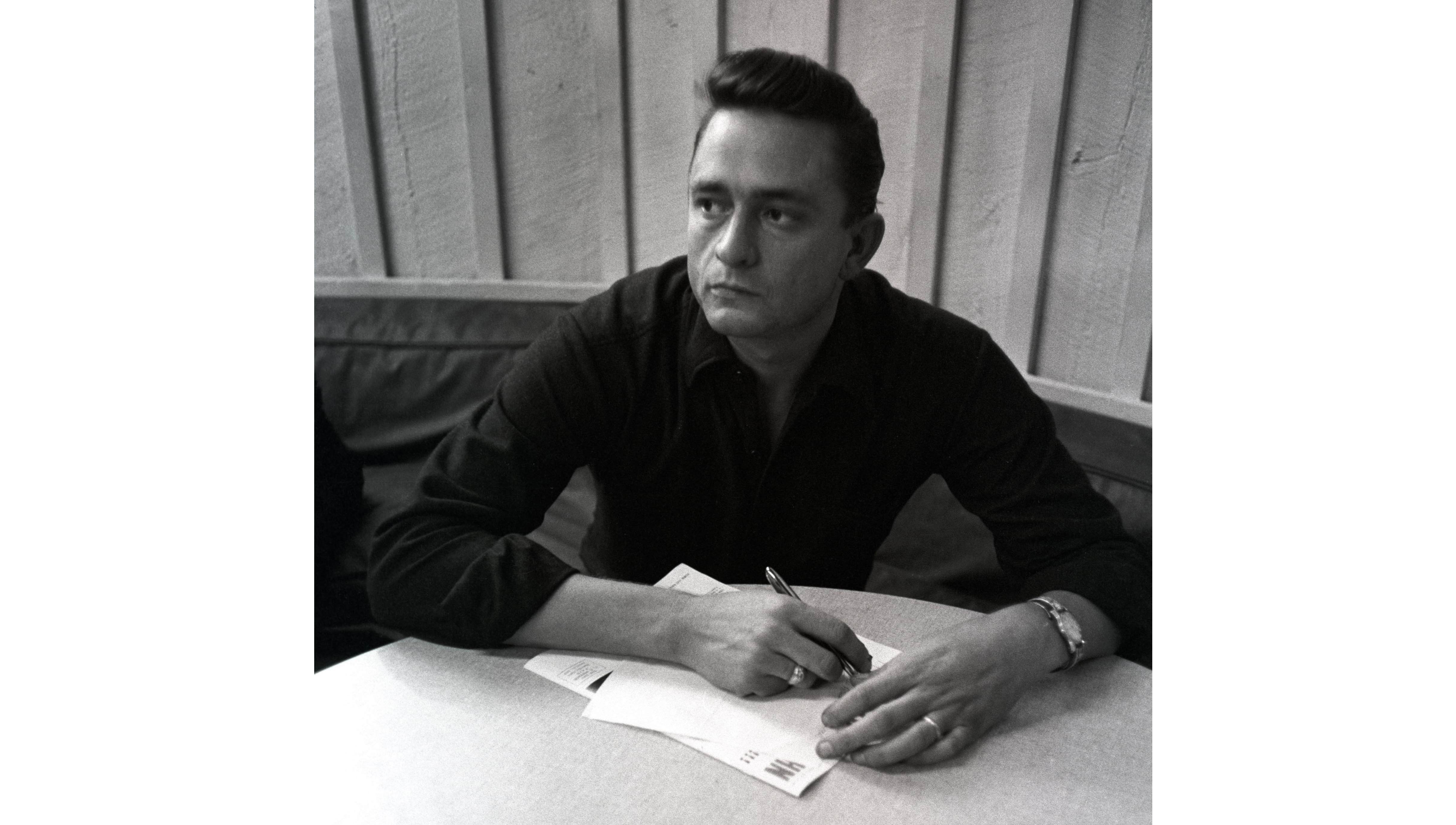

“I think a majority of people who know my father’s work would say he had a strong literary prowess, but I wanted to reaffirm that,” Carter Cash says. “He was not only an image, the iconic picture of the Man in Black; he had great depth and strength as an American literary, cultural, poetic writer. I also heard melodies in these writings.

“From the beginning, when I saw some of the poems or fragments like ‘The Walking Wounded’ or ‘Goin’ Goin’ Gone’ or ‘Spirit Rider,’ I wished I could say, ‘Dad, where’s the music? What was the melody?’ It put a fire within my spirit to know that he would have loved to have those pieces heard.”

The book Forever Words: The Unknown Poems (edited by Paul Muldoon) appeared on Blue Rider Press in November 2016; it contains 144 pages of Cash’s previously unpublished poetry, lyrics, and other personal and spiritual works. And this month the Forever Words album, produced by Carter Cash and Steve Berkowitz and engineered by Chuck Turner, will be released. It features songs fashioned from Cash’s writings by a varied group of artists whom Carter Cash selected to display his father’s broad musical influence and interests.

Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson perform the last poem Cash wrote, “Forever,” to the tune of the beloved song “I Still Miss Someone.” Carter Cash’s sister Rosanne integrates a poem called “The Walking Wounded” into a dark folk ballad. Elvis Costello creates a romantic orchestral piece from “I’ll Still Love You.” Robert Glasper sets “Goin’ Goin’ Gone” to a hip-hop groove. And that’s just a taste.

“The writing itself told us whether to hand a specific piece to a hard rock artist or a folk artist or a hip-hop artist or a pop artist, or bluegrass or modern country. It was all there,” Carter Cash says. “And Dad was open-minded that way. He came to me in the early ’90s and said, ‘Have you heard [Nine Inch Nails’] Downward Spiral?’ And I said, ‘Um, yes … have you?’ He was so open to music, and I think that worked both ways.

“So if some of these artists wanted to write their song as if Johnny Cash was in the room and he was going to sing it, great,” he continues. “T Bone Burnett did that. But if they wanted to do it from their own creative viewpoint, like the Chris Cornell song [‘You Never Knew My Mind’], that was awesome. I think some artists were excited to reach that far.”

Cornell’s track was one of the late Soundgarden and Audioslave leader’s last recording sessions. “‘You Never Knew My Mind’ was a fragment of a poem from the time in Dad’s life when he was breaking up with his first wife, Vivian,” Carter Cash says. “I listened to that song a thousand times when Chuck and I were mixing, but it’s still hard to hear.”

It was an emotional and rewarding experience for Carter Cash to research and date the writings. He believes the Jayhawks song “What Would I Dreamer Do” was written when Cash was 15 or 16 because it appears on Delta Airlines letterhead with a logo used only in the late 1950s. He was able to date the song ‘To June This Morning,’ performed by Ruston Kelly and Kacey Musgraves, to February 1970 because of the subject matter.

“In February 1970, my mother was eight months pregnant with me, when he writes about seeing my mother walk down those stairs and the light in her eyes,” Carter Cash says.

A handful of songs on Forever Words were made in other studios, but the lion’s share were tracked in the Cash Family Cabin, the refuge that Cash built on his property in Hendersonville in 1979 and then turned into a studio of sorts while working with producer Rick Rubin in the ’90s. Over the years, the family has added rooms and technology to the cabin; the current studio includes a large tracking room, a drum room (the original cabin), control room, three small iso rooms, and a natural reverb chamber that was designed by Cowboy Jack Clement.

“That was one of the primary reverbs on this project. We also have a vintage EMT plate that was once part of the Grand Ole Opry sound system,” says Turner, who engineered all of the songs recorded in the cabin.

Turner captured all of the tracks to Pro Tools at 24-bit/48 kHz resolution, then used Apogee converters to transfer all digital files over to mix via the studio’s Rupert Neve 5060 centerpiece desktop mixer.

Turner has been working in the Cash Family Cabin for more than 20 years, and he used tried-and-true recording chains on these sessions. “The main vocal chain was a vintage Neumann U67 mic, a Neve 1073 and an old Blackface 1176. I think that was the vocal chain on everything I recorded,” Turner recalls.

Most of the tracking in the cabin studio was done live with each vocalist situated in a booth and the piano in another booth. Guitar amps were usually placed in an iso closet and miked with a Shure SM57 and a Royer ribbon.

Related:

• Rosanne Cash: “The River and the Thread” Weaves Southern Influences, by Barbara Schultz, Jan. 1, 2014

• The Unbroken Circle: A Tribute to the First Family of Country Music, by Blair Jackson, Nov. 1, 2004

• Kindred Spirits: A Tribute to Johnny Cash, by Barbara Schultz, Dec. 1, 2002

“I used a Focusrite Red 3 preamp for electric guitars, and on the piano I used a matched pair of little Røde MT5 mics into Great River mic pre’s,” Turner says. “That piano is something special. It’s an 1867 Steinway upright from June’s collection.”

Turner’s drum-miking scheme was straightforward: an AKG D112 on kick, one FET U47 inside and one outside, Shure 57s on snare top and bottom (though the bottom mic is sometimes traded for an AKG 451), another 57 on hi-hat, and Sennheiser 421s on toms.

“I have a pair of AKG 414-type condensers for overheads and a pair of vintage AKG omni tube mics positioned up in the ceiling of the cabin for room mics on my drum room,” Turner says. “That space, the original cabin, is all wood. We have hardwood floors. The walls are rough-cut cedar. I have some gobos and baffles up, but in general it’s all wood and very rustic. If you drove up to this place, you would never think, ‘There must be a recording facility here.’”

During the mix, Turner applied a few consistent elements to the tracks he recorded and those he received from other studios, in part to create the feeling that the songs all came from “the same place.”

“I use an SSL compressor on the 2-mix; helps bring everything together,” he says. “I also use the Renaissance EQs and the Bomb Factory 1176 religiously. Also, I set up all my auxes and subgroups on a track, and I’ll import those into the next one and the next one and the next so that compressor or EQ or reverb stays from song to song. In that sense, this was like any other project we work on.

“But anytime we’re doing Cash stuff, whether it be John’s mother or his father, or other Carter Family stuff, there’s always an emotional side to it because of where it came from and the memories that it brings up,” Turner concludes. “I was the last one to record Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash. I didn’t spend as much time with them as some guys, but I worked with them a number of years before they passed. So seeing this material come to life—it means that Johnny Cash lives on through all of us.”