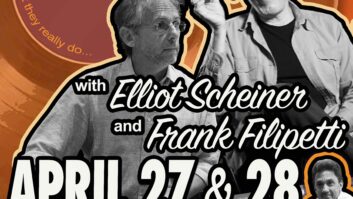

A down-to-earth guy with a refreshingly honest style, Frank Filipetti is well-respected by his peers. He’s also an independent thinker and was one of the first engineers to embrace digital. His credits include mixes for such Number One singles as Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is” and “I Don’t Want to Live Without You” (which he also produced), Kiss’ “Lick It Up” and The Bangles’ “Eternal Flame.” He’s also recorded and mixed albums for Carly Simon, Barbra Streisand, Vanessa Williams, George Michael, 10,000 Maniacs and James Taylor, whose elegant Hourglass Filipetti produced, engineered and mixed, winning Grammy awards in 1998 for Best Engineered Album and Best Pop Album.

A proponent of surround sound, Filipetti has nine 5.1/DVD projects under his belt, including works for Billy Joel, James Taylor and Meatloaf. And lately, this accomplished studio engineer has been taking his chops on the road, recording and mixing numerous live albums including the Pavarotti and Friends series, last year’s Minnelli on Minnelli, James Taylor’s Live at the Beacon and most recently, Elton John’s One Night Only. He’s also recorded original cast albums for A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum featuring Nathan Lane, the Grammy-winning Annie Get Your Gun, and this year’s Tony Award-winning and Grammy-nominated Aida, among others.

Mix spoke with Filipetti during Christmas break, when he was enjoying some time off at his New York home before heading to L.A. to begin recording the latest effort by rock/metalists Korn.

As a singer/songwriter and drummer, you actually had a musical career going when you switched gears to become an engineer.

I was brought up in Bristol, Conn., where I had a band in high school, whose claim to fame was that we got to open for the Dave Clark Five. When I went to the University of Connecticut, I formed another band called Park. After college, we made a demo tape on a 2-track Tandberg, and we took it to New York City. A producer heard it and signed us up, and we ended up moving there. After that, I had a couple of minor record deals, and, in the process, I won first prize as a writer in the American Song Festival. That led to a publishing deal with Screen Gems, where I was signed to a salaried contract. I also recorded an album for Lifesong Records as a solo artist. Upon finishing the album, I was informed that they’d lost their distribution deal with Epic, and suddenly everything in my life began to crash. Screen Gems decided not to pick up my option, and my girlfriend and I split up. She got the apartment, and there I was on my 31st birthday: no job and no place to live. I decided that it was time for a new approach. I’d been trying for nine years to make it as a singer/songwriter, and I was always so close to having something happen. But it never really did.

So the next logical step was…

I thought I’d be good at engineering, because I was always interested in sound. So I went to Simon Andrews, the owner of Right Track Studios, where I’d done my album. At the time, it was a 16-track demo studio, and I’d gotten to know Simon because he would engineer my demos for Screen Gems there. I said to him, “I’m 31 years old and it’s a little late to be changing careers. I know I can do this, but I can’t afford to be an assistant for two years. Would you give me a shot at engineering?” He said, “Why not?” So for 30 days I assisted other guys. Then he started putting me on 4-track demos, and I did very well. After six months, I became chief engineer, and, not long after that, I got a very fortuitous gig with Peter Asher.

How so?

By the end of ’81, Simon wanted to expand, and he found a pretty large space on 48th Street where we built a room. We didn’t know a whole lot about what we were doing, but somehow we came up with something. The recording area was 40 by 50 with, at that point, two iso rooms and an MCI console. We could fit a reasonably large group of people in there, and it was very inexpensive.

Peter [Asher] was producing The Pirates of Penzance, and he was looking for a reasonably priced recording space to put the whole cast in. He booked Right Track and asked for the chief engineer, moi, to do the project. He did bring his own engineer from L.A., Niko Bolas, just in case I wasn’t any good. But, after two weeks, he was able to send Niko home. From that point on, it was amazing. He took me to England with him to mix the film soundtrack, and he recommended me on several other projects. A year later, he called me about doing a James Taylor album. But first, I had to do a demo to make sure it was okay with James. So, James’ band traipsed over to Right Track one afternoon before their gig at Radio City Music Hall. I guess I did okay, because two months later, I was on my way to Montserrat with Peter and James for the That’s Why I’m Here album.

Once you decided to engineer, you had good luck.

For 10 years, I was trying to get songs to Peter Asher; suddenly, I’m traveling around the world working with him.

But did you ever sell him a song?

No. Previously, my whole life was writing songs, but once I decided to engineer I never looked back. It obviously wasn’t my calling and engineering was. And, basically, through Simon’s and Peter’s belief in me, I got my career started.

You were an early proponent of digital recording.

It’s funny about my digital journey. Around ’85, during That’s Why I’m Here, we were asked by Sony to try their new digital multitrack, which I didn’t mind as long as I could double bus. So on the tracking sessions we had a Sony 3324 and a Studer A800, and the Studer just blew it away. I didn’t like the digital at all, and for the next few years, I was very anti-digital.

What changed your mind?

In 1990, Allen Sides came to visit me at Right Track. We had a long talk, and I think we both had a sort of epiphany. I was remarking that I didn’t go home and play my recordings anymore, now that they were on CD instead of vinyl, because I didn’t really like the way they sounded. And I started thinking that maybe the approach I was taking in making them was wrong. With CDs being 80 or 90 percent of the market, instead of complaining, I should be using it to my advantage. I needed somehow to be mixing my records so that, whatever it was that digital was doing to the sound, I could at least hear it before it got to mastering. I mean, we’d be sitting in the studio playing half-inch mixes going, “Wow, this is great.” And then you’d get a CD ref back from the pressing plant and say, “What happened?”

Now, granted, the filters and the A/D converters at the time were pretty poor. But I decided that I should mix to a digital format, and, instead of listening to the console out, I should monitor after the signal was converted to digital through the machine. That way, if digital does add harshness, or take away some warmth, or dry up the ambience, I could compensate for that before I finalized the mix.

So, that’s what I did, with a Sony 2-track DASH machine that my good friend David Smith at Sony Classical got me. And, when we took the project to mastering, Ted Jensen was able to go direct into the 1630. When I got the CD back, for the first time in years my mix sounded like what I’d heard in the studio. From that point on, I mixed everything digitally.

That was an unusually logical approach to an often emotional subject.

It just made sense. I also started tracking digitally because, unlike my experience with the 3324, when the 3348 came out, I immediately warmed up to it. I did two projects with both an analog and a digital machine. What I found on the first project was that on tracking day, the analog machine sounded better than the digital. But after two months of running the tape across the heads, the digital killed the analog.

So the analog vs. digital debate took on a “he said she said” kind of thing. And I got used to not having to go in and check the tones every day and being able to sample and move things around. The flexibility of the 48-track was so much better than locking up two 24-tracks that whatever slight sonic benefit there might be [to the analog] became negligible. Slight benefit is even arguable, because, while analog sounds wonderfully warm and cozy, there are some areas where digital does a better job. For example, being a drummer, what I always missed in analog was the front end of the snare and kick. You never get that initial impact because analog is terrible on transients. The digital machine has those transients.

You were recording and mixing to digital tape but still working on an analog console. That led you to the Neve Capricorn.

Right Track was building a new room, Studio C, and I started reading about this Capricorn. The only one Neve had was at the Penthouse at Abbey Road in London. They flew me there, and I brought along some 3348 tapes that I’d just finished mixing. I was there for two days, but within the first five minutes, I had a mix that sounded better than the mix I’d done in New York. It was another epiphany.

What was it that so impressed you?

The flexibility. The idea that you can have a center section where all your work is done, where you can move tracks around at your whim. You never have to move away from the sweet spot to do your EQ or ride a fader. I do a fair amount of 96-track mixing, and when I’d be mixing background vocals on an analog console on track 96, I’d be 20 feet away from the center. On an 11-minute Jim Steinman track, that’s a long time to be listening just to the right speaker. On the Capricorn, it doesn’t matter if it’s channel 23 or 193; you can move it to the center instantaneously. That just blew me away.

You made a move that was very bold for 1994, convincing Simon Andrews to put in the Capricorn. How did it go?

When we got it to New York and started doing real mixes, it was a bit of a disaster. You’d mix for five hours, and the thing would crash and you’d be down for six hours. Three days later, it would corrupt the mix tree, and you’d lose those three days’ work. It was a nightmare. But I still had in my mind that, if we could get this to work, it would be incredible. Right Track and I lost a lot of money in billings that year. But I so believed in it, and the concept was so unique and brilliant that we stayed with it. And, at the end of that year, after endless meetings with the tech people and the R&D people and phone calls across the waters, finally we had a system that was stable and operating like the console it was supposed to be.

You’re now a great believer in staying in the digital domain once you’ve converted to it.

This was the other reason I went for the console. When I first played my 3348 tapes on the Capricorn in London, I suddenly heard the music in a way I hadn’t heard it before. I’d been working on that album for four months. I knew it well. But when I brought up the faders on the Capricorn and heard this wonderful sound, I realized it didn’t make any sense to record to digital, then mix on an analog console only to go back to digital again for the CD.

Initially, you sample the analog signal into the digital format of your multitrack. Then, to get into your console, your numbers have to be reinterpreted back into an analog waveform. You’ve taken your original signal, made suppositions about it, and reinterpreted all those suppositions only to resample and reinterpret further down the line. The more times you do this, the worse the sound gets. What happens between each of those 44,100 samples per second is predictive supposition. Ninety- eight percent of the time, they’re right; two percent of the time they’re wrong. And each time you do this, that two percent becomes four, then eight, etc. Whatever anomalies the digital process adds to the analog signal is compounded with each successive conversion.

What about degradation between digital-to-digital transfers?

Copying digitally, the main problems are clock-based. The more stable the clock, the better your copy. It’s true that, even under the best of conditions, there are questions about digital copies. But I did a test on a 3348 that was properly set up, where we recorded a piano on tracks one and two, then bounced it down 24 times. I then brought up tracks 47 and 48 on the Capricorn and flipped the phase. They canceled — on a twenty-fourth-generation copy. That was good enough for me.

I go to studios all around the world and I talk to engineers who say that they’ve tried digital, but it just didn’t sound right. And then I find out that they’re using mic cable for AES lines, or they don’t run a wordclock source. Or they’re daisy-chaining wordclock through the AES line. And, of course, it will sound terrible if you don’t do it right. Just like analog. We’ve spent 40 years massaging analog technology to work to its strengths, but people expect digital to magically happen without the same attention to detail.

People think they can just run an AES line from one machine to another, and the clock will run along that line just fine. Trust me, AES-derived clock does not work as well as dedicated wordclock, and people who are using it are making a big mistake. It amazes me that guys who will wheel in racks of preamps and vintage devices won’t insist on a dedicated wordclock. One of my pet peeves is that manufacturers are starting to eliminate wordclock inputs on a lot of their devices. I’m furious about that, because you cannot have a good-sounding digital box without wordclock. Period. All you have to do is listen to it to know that. And that’s why, in a lot of people’s minds, digital doesn’t sound good, because they may try it in studios that either cut corners or don’t know how to set it up properly.

What do you hear when the clock isn’t right?

It’s that grating, tearing, hard-edged “digital” sound. Also, the stereo width shortens. There’s less depth. It sounds smaller, more compressed and harder.

What causes that?

First of all, jitter. Jitter is exactly what it sounds like; the clock source is a moving target. Second, the AES clock actually works something like FM, where there are several data streams piggybacked on the AES signal. If you filter out the audio portion of the AES signal and just listen to the clock, you can actually hear how unstable it is. The absolute, fundamental rule in digital is the stability of the clock.

What I insist on, and what we do at Right Track, is ensure wordclock home runs to all of your important digital devices, like your multitrack, your console, your Pro Tools…

You’ve said that working on a digital console has changed your approach to mixing an album.

For years, especially since the advent of automation, the standard way of mixing has been to work on a single song until it’s done. But, with the Capricorn, I realized that I could mix the whole album. I work a couple of hours on each song, get great rough mixes, get a vibe for the whole record, then go back and start doing it again. That allows me to hear the whole album as a work, as opposed to individual songs. The old way, you’d mix a record and maybe have to remix three or four songs, because, when you’d finally hear them in context with everything else, they didn’t work.

Now I can mix in a sequence, out of sequence, place different songs next to each other — because I can instantaneously get that mix back up, and it’s identical. It’s not like I have to sit and tweak for two hours to get the mix back.

Some people say they like to get in a zone while mixing. There are times that I do, too, and when I do, I stay there. The point is, I can mix any way I want. If I’ve been working on an aggressive rock number for three hours and I need to clear my ears out, I can put up a ballad, then go back fresh a couple of hours later.

How do you deal with your outboard when you change songs?

The Capricorn has 16 sends on every channel. In addition, every function on the console is totally automatable. I usually have about 26 sends set up, using duplicate sends. For example, send eight may go to a Sony reverb or a Lexicon reverb, and I mute or un-mute them in the mix as needed.

You have a lot of different effects set up so you can switch songs without having to reset them.

I’ll have something like two sets of long, medium and short reverbs. I have several different delay devices, flangers, etc.

What about conversion delay when you use analog gear?

Most of my reverbs have predelays; or if I’m setting a delay in time with the beat, I just set it so it’s in time when it comes back to the console. If I’m using a chorus and there’s an extra millisecond of delay that the A/D conversion adds, that’s not going to change my chorus, which has a 30-millisecond delay anyway.

For the most part, it doesn’t become an issue. When it does, you have the capability of moving things either in Pro Tools or on your digital tape machine to compensate. It’s more of an issue when you’re recording or setting triggers.

What is your preferred mix format these days?

My favorite mixing box is the Sony PCM-9000, a 2-channel, magneto-optical box that sounds terrific, but which Sony has stopped supporting. There are several new boxes I’ve been testing out: I like the Alesis MasterLink, but I hate the fact that there’s no wordclock in. I’m also mixing to Pro Tools 24-bit, to Genex MO and I’m trying a couple of the new Tascam units. So far, nothing has won me over.

I’m waiting for the multichannel recorder that I can use for my surround mixes that blows me away the way the PCM-9000 did. On the Elton John recording [One Night Only], I used a Euphonix R-1, which was intriguing. I’d like to spend more time on that.

How did you come to use the R-1 for that recording?

I talked to Randy Ezratty of Effanel, because we’d done James Taylor Live at the Beacon with his Capricorn truck a few years before, and I’ve always considered that my benchmark for live recording. The Cap truck was booked that night [for the Elton show] on the VH-1 Fashion Awards, but Randy knew of another Capricorn truck [TNN’s], and he offered to split his team with me.

We booked it, and a few weeks later, Randy called up to say that he’d been talking to the people at Euphonix. Their R-1 was ready to go, and they were wondering if we wanted to use it. I discussed it with Phil Ramone, the show’s musical producer, and with Elton John’s manager Derek MacKillop, and we felt that as long as we could minimize any risk, we should go for it.

So you said, “Yes, if I can double-bus.” Exactly. In doing a live recording like this, you absolutely have to assume that whatever can go wrong, most likely will.

Because of the complexity of the show, we wanted to lock up two 48-track recorders. Elton has two drummers, up to eight background singers, a percussionist, a bass player and two guitar players, one of whom also doubles on saxophone. Also, Guy Babylon has a massive keyboard setup, and we were going to have guest stars like Mary J. Blige, Bryan Adams and Billy Joel, who was to come out with a second piano. There would be no commercial breaks or time for any changeovers. There was a lot going on.

The problem was, two 48s and two 48 backups physically wouldn’t fit in the TNN truck. In addition, we had to limit ourselves to 72 inputs. So we decided on one 48 for the main band and Elton, an Otari RADAR 24-track for Nigel Olsson’s drums and all the guest artists, and a DA-88 for the eight audience mics. We duplicated those machines for our backup, and, in addition, sent a split to the R-1.

How much rehearsal time did you get?

None. Just an hour soundcheck on Friday afternoon. There was no chance to go through each song and determine the instrumentation. It was seat-of-the-pants time.

Were your mic pre’s onstage?

Yes. I’d hoped to use a fiber-optic run from the stage to the Capricorn, which was some 800 feet away, as we had done with James. Unfortunately, the TNN truck wasn’t equipped with fiber, but we felt it essential to place the mic pre’s as close to the band as possible. If you can’t get fiber, you at least want a line-level signal going down that 800 feet of cable. The stage mics went to a splitter that went to FOH, then to 90 Aphex mic pre’s. From there, we split to our setup and to the R-1. I combined them as best I could down to 72 instrumental inputs and eight audience inputs.

You had someone onstage watching mic pre levels.

Yes. As my mic pre’s were remote, any time we’d come close to an overload, I’d get buzzed from the stage. Then we’d coordinate: He’d tweak it down two as I’d tweak it up two. Basically, I was just trying to make sure that I was getting a decent level without overloading anything.

As we were 24-bit, I had a little more leeway than on some of the other live shows I do, which are usually 16-bit. With digital, it’s very important to stay as close to full-scale as you can, because digital performs poorly as you approach the least significant bit. Every dB you lose translates into a lower bit rate. But with 24-bit, even if you’re a couple of dB down from full-scale, you’re still well over 20 bits.

Wasn’t there one of those angina-producing moments during the recording?

We did have a scare about two-thirds of the way into Friday’s show — a hiccup where the console froze momentarily. Back in my early Capricorn days, one of the first things I insisted on was that the console would always pass audio, even in the midst of a crash. And it did just that. There was some scrambling, but no one panicked. And listening back, there’s not even a hint of a problem.

For mixing, you ended up going with the R-1.

We only had six days to edit, mix, fix everything. From the show to the stores in three weeks.

I think that’s a new world record.

It was tight. We got to Right Track on Sunday, and it became clear immediately that locking up all those machines wasn’t going to allow us to mix fast enough.

Although I couldn’t do a direct audio A/B between the R-1 and the Sony/RADAR, I was able to quickly determine that the R-1 was certainly not inferior. And the fact that you can have 96 tracks of 48 k on one machine was truly a lifesaver.

A Frank Filipetti hallmark seems to be an open-minded attitude toward the new.

I try to be. I’ve developed a way of working over the years that I feel very comfortable with. But if someone can show me a better way, then I don’t see the sense in resisting it. I’ll never forget my first day on the Capricorn, or my first session in a Martha’s Vineyard cottage recording James Taylor with an 02R, or my first ISDN…there are so many exciting techniques and technologies out there. To cut myself off from them would be inexcusable. That doesn’t mean you can’t be cautious.

Working with the latest digital equipment has been, and will continue to be, a risky business. No matter how often a manufacturer says that something’s tested and ready-to-go, once it gets into the real world, it ain’t necessarily so. Because, let’s face it, most of this digital stuff breaks down to lines of code. And, if the person writing the code doesn’t understand all the permutations that are going to crop up on a recording session, you’re going to have problems. Invariably, unless the machine has been in the field for a year or two, you’re going to run into difficulties.

But you’re still willing to move forward through those difficulties.

Absolutely. How boring would life be if every new day were just like the day before. Last February, I was asked to record the songs and ceremonies of several Bushmen tribes in Botswana. We spent several weeks on safari in the Kalahari Desert catching up with various tribes. Being with these people, under a moonlit African sky as they sang and danced around a campfire, was about as far away from a New York recording environment as you could ever get. But I was able to connect with the true spirit of music in a way that is sometimes lost in our business. It was one of the great experiences of my life. To try something new, to see something a little differently, to embrace change and add it to your repertoire…to simply take a chance — isn’t that what life’s all about?

FRANK FILIPETTI SELECTED CREDITS

E: Engineering; M: mixing; P: Producer

Annie Get Your Gun cast album (1998, E/M)

The Bangles: Greatest Hits (1990, E)

Tony Bennett: On Holiday (1996, E)

Beth Nielsen Chapman: Beth Nielsen Chapman (1990, P/E/M); You Hold the Key (1993, P/E/M)

Marc Cohn: Burning the Daze (1998, E/M)

Al DiMeola: Kiss My Axe (1988, E); The Infinite Desire (1998, P/E/M)

Foreigner: Agent Provocateur (1984, E); Inside Information (1987, P/E/M)

Hole: Celebrity Skin (1998, E)

David Grusin: West Side Story (1997, E/M)

Billy Joel: 5.1 remixes for The Stranger and 52nd Street

Elton John: One Night Only at Madison Square Garden (2000, E/M)

Elton John and Tim Rice: Aida (1999, E)

Kiss: Lick It Up (1983, E)

Meatloaf: 5.1 remixes for Bat Out of Hell

George Michael: Songs From the Last Century (1999, E/M)

Bette Midler: Bathhouse Betty (1998, M)

Liza Minnelli: Minnelli On Minnelli (2000, E/M)

Carly Simon: Ten albums, including Hello Big Man (1983, M); Spoiled Girl (1985, E); Coming Around Again (1987, P/E/M); Film Noir (1997, E/M); and Bedroom Tapes (2000, P/E/M)

Barbra Streisand: Higher Ground (1997, M)

James Taylor: That’s Why I’m Here (1985, P/E/M); Hourglass (1997, P/E/M)

10,000 Maniacs: Blind Man’s Zoo (1989, E)