First, Jim Campilongo and producer Anton Fier had to agree on an approach: When they began production for Campilongo’s latest mostly instrumental album, the guitarist viewed the project as a Jim Campilongo Trio record, one that would capture the vibe and the repertoire of the guys he plays with every Monday night at the Living Room in New York City.

“I had a different agenda,” says Fier, the Golden Palominos drummer/frontman whose eclectic tastes and talents have led him to produce Drivin’ N’ Cryin’, Joe Henry and others. “I wanted Jim to make a different kind of record than he’d made before. One of the first things I said to him when we started talking about this was, ‘It’s time to paint your masterpiece.’”

Campilongo, whose eight previous albums have shown many facets of his Telecaster mastery, and who lately plays with Norah Jones’ Little Willies as well, was a bit leery of making what he calls a “business card record.” “You know what I mean,” Campilongo says. “It’s ‘Joey plays Albert King blues. Joey plays Wes Montgomery jazz. Joey does red-hot country pickin’.’ I’m not putting down proverbial Joey, but I feel uneasy during those records. The records I’m usually attracted to are like: It’s a rainy day, I’m going to put on Joni Mitchell Blue. Or it’s a crazy day, I’m going to put on Miles Davis On the Corner. I was worried that my record would switch and sway in an unnerving way where you couldn’t really hang with it. But I have to say I really feel differently now.”

It’s one of those intangible things, but Fier and Campilongo definitely created tracks that coalesce beautifully. From his almost Hendrix-like aggression on the opener, “Backburner,” to the airy “Blues for Roy,” to the bittersweet solo performance of “When You Wish Upon a Star” that closes the album, the tunes are unified by Campilongo’s musical soul and character.

Engineered by Yohei Goto, Orange was tracked at Brooklyn Recording and One East (both in New York City). As creative recording and budgeting require these days, different studios served different purposes. Basic tracks were cut in the big Neve room at Brooklyn. Fier says Goto was the perfect engineer for the job, in part because he had previously been on staff at both of the facilities.

“The Neve at Brooklyn is two custom sides of an 8068 that are put together,” Goto explains. “The right side and left side are customized differently. It’s a little hard for people who use it for the first time, but it sounds great. I was an assistant there five years ago. That’s why I could do things really quick, which was important because we only had three days. It’s a really nice studio. There aren’t many studios like that in New York anymore — the room, the mic selection, the board, the gear, big room — but we can’t afford hours and hours working there.”

Goto made an abbreviated schedule work by setting up extra microphones to capture all of the styles and nuances of the trio’s playing. “For example, I put up two different sets of overheads [on Tony Mason’s drums],” Goto says. “One pair was Coles 4033 ribbon mics — not a sensitive mic — so it’s good for the hard-hitting rock sound. But they’re not as good for subtle jazz music, so I had to put more sensitive mics up also: Neumann KM254s. They are the opposite — way more sensitive than the Coles to pick up the little subtle things like brushes. We let them just play it, and then later on chose which mics to use from those two overhead sounds.

“The other thing that was a challenge was we recorded [all of the basic tracks] live without headphones,” Goto continues. “Everybody is in the same room, and Jim doesn’t want headphones. So next to Jim is the [stand-up] bass, and it’s hard to hear that to Jim when he’s playing live.”

Goto took a DI from the bass amp and set up a speaker in the tracking room so that the guitarist could hear Stephan Crump’s bass. When it was time to mix, of course, the live recordings posed some engineering challenges because of the bleed that all the close-miking in the world can’t eliminate.

“Everything is one,” Goto says simply. “If you EQ the bass, it will change the sound of the drum and the guitar because everything is one.”

But the feel of recording as one was exactly what Campilongo was after: “I don’t like to wear headphones when I play. I don’t want to re-create this thing we’ve done at 12:30 at night with a great sexy audience watching us, and we’re playing and it feels like we’re all in it together, and then go into a recording studio at two in the afternoon and put on headphones and try to get the same kind of performance. It’s a tough thing to do.”

Goto transferred the tracks from the Brooklyn sessions into Pro Tools, and then brought them to Matt Wells’ One East, a studio Fier says he really appreciates because it is a rare “affordable Neve room, with one of the best control rooms I’ve heard. You can listen very quietly and still hear everything accurately.”

At One East, Campilongo tracked his solo pieces (“Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful,” and “When You Wish Upon a Star”) and two duets with guitarist Steve Cardenas, and overdubbed some guitar parts. This was also where Goto recorded Campilongo and singer Leah Siegel’s dark and beautiful performances on two of the cover tunes that Fier helped select — The Stones’ “No Expectations” and Iggy and the Stooges’ “No Fun” — and where the album was mixed.

“Selfishly speaking, I like records that go on a journey,” says Fier. “Jim had already made records documenting the current bands he had in the studio, and I thought it was time for him to do something different. What makes this work is Jim has his own voice. He has his own sound, which, as a musician, is what one strives for one’s entire life.”

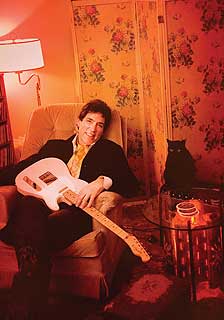

Photo: Arthi Krishnaswami

Jim Campilongo’s Music Evolution

When we spoke to Jim Campilongo for an article about production of his latest album, Orange, he shared much more from his perspective as a guitarist than we could include in print. So, for anyone who wants to know more about how Campilongo’s music has evolved, and how Orange came together, enjoy:

Your producer, Anton Fier, says that the two of you originally had two different ideas about the direction of this album, where you wanted to capture a “moment in time” of the Jim Campilongo Trio, but he wanted you to show a broader view of your playing and style. Could you talk about how this coalesced into Orange?

Anton wanted to demonstrate some of the extreme aspects of my writing style, so he pushed for a few things [to be included on this album]. One was track 2, which is called “Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful.” It’s kind of a Chet Atkins thing.

Anton came over to talk about material for the record. We had taped a number of live trio performances at The Living Room, and there was so much material because I write a lot of stuff, and it had been two years since I recorded an album. I don’t remember what I had—25 or 40 tunes, way too much—and I happened to be working on that tune, which originally I wrote for someone else.

I had been to see this country swing band at Barbes, which is a club in Brooklyn, and for some reason I came home, and I had internalized some of the music, and I thought, “I’m going to write them an instrumental.” Sometimes as a writer I give myself an exercise that transcends a deep need to express some innermost feeling. I’ll just say, “This is my task. I’m going to write a song for this individual.”

Or sometimes I write down titles before writing a song, and say, “Okay, what does ‘Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful’ sound like? What is that song?” That was my exercise, and I’d written it, and Anton came in, and he really liked it, and he said, “Why don’t you put that on the record?”

I said, “I don’t want to put that on the record; that’s kind of more what I used to do than what I do now.” But he said, “No, that’s your thing.” And I was very malleable in the making of this record. I produced the last two Jim Campilongo records and a Christmas record, and I just didn’t want to produce [Orange]. I wanted somebody to tell me what they wanted, and to some degree to do it. So we put it on the album.

What’s the second song you meant?

Originally, we were thinking about having the record open with that song, and then Anton had me come up with a solo piece, and I was apprehensive about that. That was “When You Wish Upon a Star.” I was self-conscious because sometimes people get too smart for their own good. I said, “Playing solo, that’s something I do, something I have done, but I don’t know if it’s worth putting on a record.” But due to Anton’s total influence—I never would have done this if I had been producing the record—I tried to play the tune like the guy didn’t get his wish. I wanted it to sound bittersweet, and because of that reading perhaps, it came out nice and I was happy with it.

It sounds like you were open to exploring Anton’s ideas, even when they didn’t fit with your original vision.

This is my ninth Jim Campilongo record, and the way I’ve learned to make records is I don’t assume anything. I remember my second record I made, which is called Loose. I had written a song and I was so happy with this song, and I thought it was the best thing I’d ever written, and I decided before recording that I would name the record this song’s name. I had gotten an artist to interpret this song title [for the cover art], and when we went to record, the song didn’t work. We had to fight it. There was a problem with the tempo, a problem with intonation. The day I was supposed to solo, I couldn’t really get it. Everything was hard. And it just wasn’t what I wanted it to be, and then I had to change the name of the record, get new artwork, all that stuff. So I learned you just don’t count your chickens before they hatch.

Photo: Arthi Krishnaswami

So when we went to make this record, I knew we had a bunch of great material, but I was really committed to put on only what I felt was stellar, and so we recorded for a couple of days, and we came out with some really stellar stuff as a trio, but there were a couple of tracks that we felt weren’t great, and we wanted everything to be great. So we had room for other options, but the other thing I thought—actually, this is important—I always want to make short records. I’m an instrumentalist. I play the Telecaster. It sounds pretty much the same on every song. Of course there’s dynamics and stuff, but it gets tedious after awhile. I really believe in leave ’em wanting more. I’m never one of these guys who will play a two-hour set. I’m always looking at the audience, and if I see anybody even shift in their seat, I’ll make it the last song.

Anton was really adamant about making it a lengthy record, though, and I was worried about that. But because it’s a lengthy record, it allowed us to put on the two by Leah Siegel, the vocalist. One is much different from the other. It also allowed us to put on an acoustic duet. So it ended up working out, but I was concerned it would sound like a business card record.

You mean like, “Here’s everything I can do?”

Exactly. I call those business card records. It’s “Joey plays Albert King blues. Joey plays Wes Montgomery style. Joey does red-hot country pickin’.” I’m not putting down proverbial Joey, but I feel uneasy during those records. The records I’m usually attracted to are like, it’s a rainy day and it’s dark out, I’m going to put on Joni Mitchell Blue. Or, it’s a crazy day, I’m going to put on Miles Davis On the Corner. I was worried that my record would switch and sway in an unnerving way where you couldn’t really hang with it. But I have to say I really feel differently now. I don’t listen to it a lot, but it’s kind of like an iPod Jim Campilongo shuffle. After one song that’s dark and brooding, there’s some comedy relief now and then, and it worked out; it ended up being a 61-minute journey where you don’t get too exhausted because there are peaks and valleys.

When you were talking about the song “Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful,” you said it was what you used to do, as opposed to what you do now. Could you explain that?

When I first started writing under my own name, I was really influenced by Jimmy Bryant and Speedy West and other hot country instrumentalists, and I worked in a band [Jim Campilongo and the 10-Gallon Cats] that was very much coming from that place. They were versatile, but there was a certain personality that those players had, and myself. And eventually any band becomes bigger than any individual. Even if you’re Frank Zappa and you’re in the Mothers [of Invention], you’re going to have to write a song so the Mothers can play it successfully as a whole entity. That served me very well, and I’m very proud of my first record [Jim Campilongo and the 10 Gallon Cats], but after a certain point, I felt I had changed a bit as a writer, and I did this record Table for One, which is very cinematic, and I think is a beautiful album. I used an organist and an accordionist. I changed and felt I needed to say this other statement, and since then I’ve gone through different changes.

Upon moving to New York and working in the trio, I started using a lot more space—playing minimalistically in some ways and learning that you can really relax in a trio. Sometimes when you’re a guitar player, you’re thought is, ‘How can I sell this or make it sound bigger?’ But I had the revelation that I really don’t need to do that because sometimes it sounds better if I just don’t play. Sometimes hearing a brush wipe across a snare drum, or a cymbal or the growl of an upright bass—there’s nothing wrong with that if you pause for four or five seconds.

I’ve really became committed to that kind of approach, and now it’s 14 years after that first record, and that’s how I meant it when I said, “something I used to do,” in that it was a two-beat, and somewhat whimsical. A lot of my writing on my first couple of records had a lot of whimsy to it. They’re kind of perversely humorous. And so that’s how I mean it, but I certainly wasn’t being cynical in any way. I’m really happy with that track [“Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful”]. I’m glad I had a producer to cajole me into doing something that eventually I thought was a great idea.

Photo: Arthi Krishnaswami

Anton and your engineer, Yohei Goto, told me you were insistent about not using headphones during basic tracking for this album. Tell me your feelings about that.

One thing I really get a little frustrated with is, when I’m recording, the end result is sometimes I will hear from people that, “It’s nothing like seeing you guys live.” And generally with the past couple of records, it did seem that for some reason I didn’t really articulate what I really wanted. We’d get to the studio and it would be a nice room, but sometimes somebody would talk me into putting my amp in another room or using headphones because it’ll track a lot better. But as a musician, it’s not just the Jim show. You don’t want your amp pointed at the drummer’s head and go, “Well, suffer, this makes me sound cool.” But there were always these compromises, and in the end, I just didn’t enjoy it. It was almost like I would have to try to remember what I would play if I was really and truly inspired.

Some of that has to do with the fact that I think I’m more a performer. If there’s people watching and listening and connecting, I feel that energy and that human spirit. I feel inspired when people are listening. But in the studio, it’s almost like you have this conversation with yourself, which can be effective, but sometimes it’s a conversation that’s really negative: “You could do better,” or “That was good, don’t blow it now.” There’s all this dialog you’re having that isn’t just about listening. So I really put my foot down on this record and said, “Look, I want to play some tunes really loud. I really want to be next to the drummer. I want to hear and feel the drummer. I want to have eye contact with everybody, and I don’t want any bleed.” And so Anton, to his credit, really tried, and Yohei really tried to make that happen, and to some degree I think it did.

I just don’t like to wear headphones when I play. I like to hear the overtones and I like to hear the cymbals, and I feel like it’s such a different sound. I can wear headphones if I’m overdubbing or I’m at [someone else’s] session, but when I’m doing my thing… We play live every Monday. We have a residency at The Living Room, and I don’t want to re-create this thing we’ve done at 12:30 at night with a great, sexy audience watching us, and we’re playing, and it feels like we’re all in it together, and then go into a studio at two in the afternoon and put on headphones and try to get the same kind of performance. It’s a tough thing to do.

Yohei also mentioned that you used a different amp from your usual Princeton on one song. What was it, and what did you get from it that you needed to be different from the rest of the album?

We recorded this tune Backburner, the first tune on the record, and during the first series of recording sessions, I felt like we just couldn’t get it. I think it was me. I was screwing it up.

The most amount of takes we had on one song on Orange was “I’ve Got Blisters on my Fingers,” but we did that because it was fun, and each one was different. That particular song, I think we had at least nine of them that were all really good, really open, and all different from the others. There was this Jimi Hendrix record that Alan Douglas put out five or six years ago, and it was all these different versions of “Red House”; the whole record was just one song in different versions. If I ever become a bigger celebrity, then perhaps I would put out a record some day that’s all “I’ve Got Blisters on my Fingers,” because we’ve got nine versions and they’re all pretty good. But I would definitely not want a record of all “Backburner,” because I was messing it up and not getting it.

Anton really wanted it on the record, and sometimes I get—even though I’ve made a lot of records, and I’m no spring chicken and I have a good attitude—I can get a little disillusioned. I said, “Oh, screw ‘Backburner,’” and he said, “We really have to get it.” And I kept listening to what we did, and I thought we really didn’t have one we could use.

Photo: Todd Chalfant Photographer

So I set up a day for us to go back to the original recording studio [Brooklyn Recording] and record “Backburner,” just “Backburner.” It killed me. I’m spending all this money on this tune I don’t even want to record. I’m sick of it. So [before we went back to Brooklyn], I had this errand to do of having to listen to all of the basics, and [I remembered that] the first day we’d decided that the sound [on the track] wasn’t room-y enough, and we had moved stuff around, and everything we kept was from day two and three. I listened to stuff from day one, just listened to “Backburner”s. I remember sitting there, listening to “Backburner” number three or four from day one, and I thought. “That’s pretty good, I didn’t remember this one.”

So I called up Anton, and I said, “You know, my solo is not so great on it, but it’s day one and there’s no bleed. I think I could overdub the guitar.”

We checked it out, and the rhythm track is awesome and there’s no bleed, so then it’s the day for me to record a whole bunch of stuff: overdub day. And if we got everything we’re supposed to do that day, we could move on and be on schedule and we wouldn’t be spraying too much money out of a fire hose onto our album efforts.

So we go in [to One East Recording], and I said, “Let’s do ‘Backburner,’” and I plug in and I play, and it isn’t happening, and I do it again, and it’s not great. I do it again and it’s okay, and I say, “I think it’s pretty good,” and Anton says, “You can do better.” Then I do it again and it’s worse, and it’s getting worse and worse, and time is going by, and it absolutely destroyed overdubbing day number one. So finally, and I never do this, we quit. I said, “Let’s just stop. We’re wasting time and money. Let’s just do something else,” and I actually did a great take for “Awful Pretty, Pretty Awful,” which was so needed. Then I said, “I want to do ‘Backburner’ again.” And Anton said, “Are you sure?” And I said, “Yeah,” and then I failed miserably a bunch more times, and that was the end of overdub day one.

Then we went back and finished everything else, and it was, “Okay Jim, it’s time for ‘Backburner.’” And I plug in and do one pass, and it’s just not good, and I looked around and I saw this other guitar laying there because there’s a little guitar repair guy in [One East owner] Matt Wells’ studio. It was one of the guitars he was repairing, and it belonged to a friend of Anton. I picked it up, and it’s not like a Telecaster I would normally play. It’s hollow body. It’s called a Thin Line. It’s got two F holes in it, and it’s got these incredibly heavy strings on it—I mean like piano strings—and I go, “I like this guitar.”

So, I’m playing it, and for about three days, both Yohei and Anton had been telling me, “Matt Wells has this amp, and some guy offered him $20,000 for it; it’s amazing.” So, finally Yohei goes, “Why don’t you plug in the Matt Wells amp?” And I go, “Fine!” So I plugged in that amp, and I have this weird guitar, and I started playing, and I’m in the control room and the amp’s in the amp room, and I think, “This sounds incredibly great!”

Yohei comes in and says, “What do you want me to change?” And I said, “Nothing. Just whatever you’ve got it set on, keep it there.” So I did a pass on “Backburner,” and it was fantastic. I don’t mean to sound conceited, but after everything that had happened, it was pretty much the performance. We might have gone back and done a couple of things on the chorus later, but it just sounded magnificent, and I was so grateful, because we just sweat blood over that tune from the first day. So that’s the amp story. Between the guitar and that amp, it just had a ferocious sound.

Mostly I just played through my Fender Princeton and Fender Vibrolux [amps], though. I’ve learned some things about how to get the sound I like from Darren Roven, who was an engineer on my other records, about miking guitars. One thing I like to do is I like to get the track and play it into the room again and record the guitar going into a room. On some things we not only had that, we would also add the plate reverb on top of that. I really like that faraway sound.