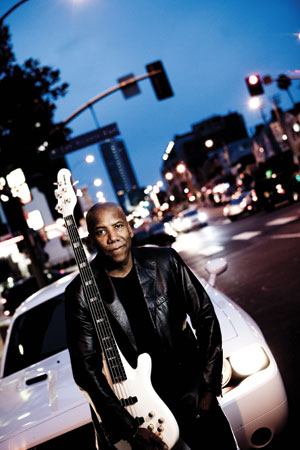

Photo: Karen Hill

Bassist Nathan East has played on literally hundreds of albums by musicians of every stripe over the course of an extremely successful career that dates back to his teenage years, when he played as part of Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra. The San Diego native established himself as a top L.A. session bassist by working tirelessly and flexibly in whatever genre was required. So his name has popped up on albums by such diverse artists as Stanley Turrentine, Jeff Lorber, Kenny Loggins, George Benson, Randy Newman, Rickie Lee Jones, Michael Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Eric Clapton, Manhattan Transfer, Eurythmics, Ry Cooder, Bob Dylan, Quincy Jones, Patti Austin, Justin Timberlake, Whitney Houston, Herbie Hancock, Stevie Wonder, Daft Punk (he’s all over their recent Grammy-winner, Random Access Memories), as well as dozens of film soundtracks and, of course, his mega-successful smooth jazz band of the past 23 years, Fourplay. He’s also written or co-written songs that have been recorded by a number of top acts, and been an in-demand live bassist, touring for many years with Eric Clapton, and also playing with George Harrison, Andrea Bocelli, Toto, Phil Collins and many more. The guy’s a really good singer, too.

Yet 2014 is a watershed year for East: This spring marks the release of his self-named first solo album, co-produced by the bassist and Chris Gero, who heads the Yamaha Entertainment Group label. (East has been playing, endorsing and designing basses for Yamaha since the early 1980s.) As you might expect, the songs on the Nathan East album are all over the map stylistically (after all, no one has ever successfully pigeon-holed him), and includes a killer crew of first-rate musicians and singers. There are a number of recognizable cover tunes, such as instrumental takes on Stevie Wonder’s hoppin’ “Sir Duke” (East plays the melody on ultra-funky bass) and “Overjoyed” (with Stevie on harmonica); Steve Winwood’s “Can’t Find My Way Home,” featuring Winwood’s Blind Faith bandmate, Eric Clapton; a startling big band version of Van Morrison’s “Moondance,” arranged by Tom Scott and sung by Michael McDonald in one of his most soulful performances; McDonald’s own “I Can Let Go Now,” with Sara Bareilles on vocals; a lovely version of “Yesterday” spotlighting East’s young son Noah on piano; and a stirring and ambitious arrangement of “America the Beautiful.” East also co-wrote three fine originals, my favorite of which is the breezy, Brazilian-tinged “101 East Bound” (though “Daft Funk” lives up to its title, too).

Among the many notable musicians helping out are Fourplay members Bob James (piano; he also wrote the album’s superb jazz number, “Moodswings”) and guitarist Chuck Loeb, keyboardists Jeff Babko, David Paich and Greg Phillinganes, guitarist Ray Parker Jr., percussionist Paulinho Da Costa and drummer Ricky Lawson, who died before the album was finished but played on most of the tracks. Producer Gero played guitars and keys and also worked heavily on the arrangements. Lendell Black was the string orchestrator and conductor. The principal engineer and mixer on the project was Bryan Lenox, who works out of the Nashville area and has scores of impressive engineering, mixing, production, songwriting and musician credits, including Michael W. Smith, Elton John, TobyMac (whose Alive and Transported album earned Lenox a Grammy in 2009), Quincy Jones, Kirk Franklin and Sarah McLachlan. Because of East’s crazy-busy schedule (talk about in-demand!), it took nearly 10 months to complete the album, which was recorded at a number of different studios.

“We started off doing preproduction in Nathan’s personal studio in the Tarzana [L.A.] area,” Lenox explains. “Then we did the main band tracking at Ocean Way in Hollywood using between four to six players at a time over a period of about seven days, so it would feel like a band and have synergy as a whole. Chris [Gero] would actually sit in the middle of the tracking room with the musicians and experiment until it was amazing. Then he’d point to me to start recording official takes—though we recorded all of the rehearsals and jams, too! It’s always cool when musicians are spontaneously inspired by playing all together.

Left to Right: Ricky Lawson, Noah East, Nathan East, David Paich, Tim Carmon, Chris Gero, Michael Thompson, Bryan Lenox.

“We recorded the orchestra at Ocean Way Nashville—an amazing old church converted to world-class studio,” Lenox continues. “We then did a bunch of overdubs—keys with producer Chris Gero, Nathan’s solo basses, background vocals and choir, and Michael McDonald’s vocal—at YEG [Yamaha Entertainment Group] Studios in Franklin [near Nashville]. Then we went to the House of Blues recording studio in Encino [Calif.] for Ray Parker Jr.’s guitar, Tom Scott’s saxes and Rafael Padillo on percussion, and back to Ocean Way in Hollywood to record the Big Band for ‘Moondance,’ and Sara Bareilles’ vocal. Eric Clapton graciously recorded guitar over in London. Finally, we moved to my mix room in Franklin, which is conveniently located across the hall from YEG’s studios.”

The album is, not surprisingly, a splendid showcase for East’s mind-blowing bass work in many different contexts, from standup bass (a Yamaha SLP 200 Silent Upright) to single and multiple electric models (including his Yamaha BBNE2 five-string and six-string basses), deployed for everything from hauntingly lyrical ballads to slap bass funk numbers. How do you capture one of the world’s greatest bassists in the studio—a DI and a mic (or mics) on an amp(s)?

“I started by talking to Nathan about his recording chain and also about using different amps for the tracking sessions,” Lenox says. “He said he typically doesn’t record through an amp and that he has experimented for years but almost always just uses the DI. So I convinced him to try an amp I wanted to show him, and the truth is the rental amp we had didn’t sound amazing to me, and we ended up getting such a fantastic DI tone that I didn’t bother swapping it out. Nathan was right!

“I would swap out components depending on the song, but the main chain I used consisted of: A yellow Radial Firefly DI or an Avalon U5 DI; a Neve mic pre; GML EQ, to be more precise with cutting; GML compressor—you can squash it and not hear any compression; Pultec EQ, for adding the round bottom; Distressor, for gluing together and adding some vibe to the sound; and a very big- and fat-sounding [RCA] BA6A old-school limiter. For overdubs, I substituted an LA-2A for the BA6A in limiter mode before going to tape. We used the [Endless Analog] CLASP system for recording through tape and transferring to Cubase seamlessly. I like to record with multiple compressors on low ratios, so no one compressor has to overwork and sound squashed. I want it to sound natural, but also have a lot of personality and pop through the mix. For the Silent Upright I used pretty much the same bass chain, but also used a Peluso P12—which is a C12 clone—on the fret board for finger noise. Peluso makes some incredible replications, and his own designs as well.”

Bryan Lenox

The other instrument that jumps out on many tracks is the acoustic piano, mostly played by Jeff Babko (who is Jimmy Kimmel’s band leader). At Ocean Way Hollywood, Lenox put a pair of AKG C12 mics on a Yamaha C7XSH piano, run through the console’s Neve mic pre’s (with very little EQ) and a Neve 33609 compressor “for some glue, if needed; very low ratio.”

As Lenox noted, Steinberg Cubase 6.5 was a primary tool in recording Nathan East. Lenox says that he started using Steinberg products way back in 1987 with Pro24, then Nuendo and Cubase. “I’ve done double-blind tests with several other people, comparing exact files and levels to other DAWs out there,” he comments, “and every time Cubase or Nuendo won out sonically. So many of the features are essential to my workflow. There’s an EQ on every channel strip already there, waiting to be manipulated quickly. I can grab many groups of channels and rearrange in one move. There’s non-real-time exporting. I can route external gear in the inserts section, all with latency corrections. I’m able to manipulate multiple track levels and fades of any waveforms at one time, even while recording on another track. MIDI editing is a breeze and very flexible. And, of course it has an unlimited track count. Beyond that, it’s intuitive, easy to use and sounds great.”

Lenox says that one of the biggest challenges of a project with this large a scope was having good file management, because of recording in several cities and having lots of takes. Chris likes to keep all the takes, just in case he wants to go back in time, to see if there’s a previous take that he prefers. It was also a challenge mixing higher track counts—like ‘Daft Funk’ had 380 tracks!”

Asked about the particulars of this mix, Lenox notes that he uses RADAR for D/A conversion and then runs 16 channels through an Inward Connections Mix690 summing box; then into a UA 2192 converter for the A/D final print.

“On lead vocal or solo bass, I run through a hardware GML compressor and then a Tube Tech CL1B. The main bass sound runs through a [Chandler] Germanium Tone Control EQ. For mixing, I use a lot of the Waves SSL E-Channel strip and a ton of the UAD plug-ins—Pultec, Neve 88R, Fairchild, 1176, and others. I also use the [TbT] TLs pocket limiter quite a bit. For delays, I use a lot of the Sound Toys EchoBoy, and I create my own echo flange four-head tape delay that I use on almost every lead vocal—it’s a filtered EQ, going into a flanger, going into a four-head tape delay. For reverbs, I’ve been using Altiverb, mostly grabbing Lexicon 480L settings. I’ll typically use Auto Park, Fat Plate, Large Wood Room and Large Hall. And I’ll often layer a slap-back very slightly behind the vocal for mild imaging, as well as a shorter ’verb super-slightly, and a blended custom echo flange and one of the 480L sounds. I know it sounds like a lot, but layered properly and with a highpass around 200 Hz, it can be really cool.”

So much technology, but always in the service of high art. Nathan East is an album that stands up well to multiple listenings, revealing new details each time—a part you might have missed or some intriguing audio touch. First time out as a solo act, East has hit it out of the park.