Though the church played a large role in his youth, and he possessed an ear that led to his role as music director of an adult men’s choir at age 12, Kirk Franklin came relatively late to gospel music. It wasn’t until about age 18 or 19, he says, that he started paying attention. Growing up, he was all about pop and R&B, some of the funk, hanging with his friends. When he turned back to the church—the message and the choir—following the death of a friend, he was still a boy. Today, some 25 years later, he has won 12 Grammys and is one of the biggest-selling gospel artists of all-time.

It would be hard to exaggerate how big Kirk Franklin is within his genre, even outside his genre. His debut record in 1993, Kirk Franklin & The Family, featuring a 17-voice choir of mostly friends and family, spent 42 weeks at Number One on the gospel charts and went Platinum. The group’s third release, Whatcha Lookin’ 4, went two-times Platinum and earned Franklin his first Grammy for Best Contemporary Soul Gospel album.

He has gone on to release many more albums, write songs for film and television, collaborate with some of the biggest artists of the day, and roll his infectious and spirited roadshows across the country, from intimate theaters to barnstorming megatours, over the past 25 years. He has weathered some ups and downs, as most of us do. There have been new choirs, old lawsuits, highs and lows, a solo career. He’s added producer to his card, and he likes working with new talent. He has matured as an artist, while keeping his sound fresh.

And in July of 2017, he officially opened Uncle Jessie’s Kitchen, a world-class studio designed by the Russ Berger Design Group in the heart of the downtown arts district of Arlington, Texas, his hometown. It’s the fulfillment of a long-held dream, to have a space in the Motown style, where he and his friends—his collaborators and musical partners—can write, create and produce great music, music with meaning.

“The genre of music that I come from, that experience, was always best appreciated live,” Franklin says. “We had a sound truck pulling up to the church or the arena, and then of course you would go into the studio to mix. I didn’t develop a romance with the studio until about my second or third album, when I was about 24 or 25. That’s when I started to go, ‘Okay, this is getting big. It’s exciting. It’s exciting to listen on the big speakers, to see the tape machine in the corner and the big reels of tape. To sit at the board and do your own comps. That’s exciting. When you hit the mute and solo—it’s an incredible experience.

“But the most beautiful thing about studios is that they literally breathe creativity,” he adds. “They create an atmosphere where you want to be creative because you have all this uniqueness around you, this feeling in the room. I’ve been in studios that feel cold, where I don’t even want to be there very long. When I’m in a studio, I’m in there for hours and hours and hours. I sometimes don’t know what day it is, So what was most important to me in building this studio was that I wanted it to feel like a home. And Russ was very much for that.”

The relationship between Franklin and Dallas-based studio designer Russ Berger goes back to the late 1990s, when the former asked the latter to come take a look at his house. He wanted to put in a studio. “I showed him some spots I was thinking about, different parts of the house,” Franklin recalls. “After a while he pulled me aside and said, ‘You know what? Let your home be your home.’ I will never forget that.”

Berger says: “It would have cost him a lot of money, and he would have been restricted in what he wanted to do. I have learned that if you talk somebody out of doing the wrong thing, they will often come back.”

It took about 15 years, but Franklin did come back. In the interim, he had worked in various studios, toured a lot and in 2005 settled into a long-term relationship with Luminous Sound in Dallas. But the 90-minute commute each way—a “creativity killer”—took its toll. His kids were growing up, and he wanted to be more a part of it. So he started looking at buildings in downtown Arlington, 10 minutes from home. Right away, he ran into Alan Petsche.

“I was getting ready to start a label, again, try it one more time.” Franklin says. “I had just done a new deal with RCA. As part of that deal, I wanted to find a place where I could work with new artists and do my own thing. So I went looking at some buildings, and it just so happened that I ran into a building owned by an incredible guy who loves music, Alan Petsche. He and I became the best of friends. He became excited about my vision, and he has a vision about Arlington. We came together in this spot.”

Petsche, a retired businessman, Arlington booster and lifelong musician, had recently returned from two days recording at Abbey Road for his 50th birthday bucket-list present and was thinking of building his own studio in the space at the time, but stepped aside when he realized what Franklin might mean to his beloved hometown.

“When you talk about the life of a community, it begins with music and the arts,” he says. “It’s in the diversity of the students at UT-Arlington and in the Levitt Pavilion free concert series. It’s in the food and the arts fests. I have seen so many talented artists from the Dallas-Fort Worth area who didn’t quite make it, because we’re not New York or Los Angeles. I always thought that if I achieved some success, I would want to give back to the local music community. Then here comes Kirk Franklin, the most talented, sincere and wonderful man I’ve met in my life. It’s now his studio, and I couldn’t be happier for everyone, including my hometown.”

Over the next four years, the two-story property was completely gutted; half of the first-floor ceiling was removed to give height to the studio, control room and iso booths; slabs were poured, then floating floors put in; walls went up, and the ceiling was laid on top for complete room-within-a-room construction (an active rail line runs 75 yards away); and the studio took shape, along with a smaller production room to feed it. Upstairs, offices and accommodations were laid out for Fo Yo Soul Entertainment, Franklin’s five-year-old label and production company.

The studio itself contains some of the trademark Berger characteristics, with lots of natural light, floor-to-ceiling glass between control room and studio (“You feel that you’re right there with the artist,” Berger says, “and if you’re cutting bass or DI guitar in the control room, you’re three feet away from the drummer, through the glass.”), and a noise floor that extends below the threshold of hearing. (“At a number of frequencies we’re 10 to 15 dB below zero; way below an NC15 rating.”)

It’s also a Berger trademark that the job is not about him. His company philosophy has always been that no matter how big or small or whiz-bang the job, he and his team build rooms for people and the way they work.

“Because the majority of my music is choral, I did want a room that was big enough for a solo artist or a band or an ensemble or a choir or an orchestra—just to be able to have that flexibility,” Franklin says.

“At the same time, we wanted to have an environment that allows for the spontaneous. So Russ did some really cool things, like he wired the lounge. If you’re in the lounge and feel creative, you can put up mics and grab headphones and record. When we’re playing in the control room, there’s probably a bass player with me in there, a lead player, learning their parts. There may be a couple of singers. Maybe a scratch track or something I want to lay down at the last moment. There’s a lot of fluidity in the rooms.”

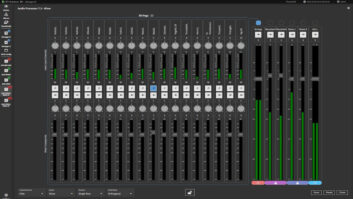

The control room features an SSL AWS24 console, Pro Tools, and a pair of free-standing Quested Q412s with a pair of custom QSB118 subs, of the same pedigree as a pair Berger put in Whitney Houston’s studio years ago. Those were pink-noised at 135 dB at the console. Franklin likes to listen loud, Berger says, but not that loud.

During the four years of plans and construction, while getting to know Franklin and the way he likes to work, Berger saw the opportunity to introduce something new to the design, something he had wanted to employ for many years in a studio environment, the eCoustics Systems Electronic Architecture. Franklin installed the prototype.

“You know LARES, right?” Berger asks, referring to the high-end Lexicon system of changing a room’s reverb characteristic through mics, DSP and speakers. “eCoustics Systems is formed from LARES—David Greisinger and Steve Barbar. They have a system that is used in concert halls and performance spaces around the world. I’ve worked with them for a few years on developing a system that would be affordable and optimized for use in small rooms.

“They’ve continued developing the platform and special algorithms that can also run in software and without need for a dedicated hardware-based processor like a SHARC, so now you’re talking much less cost and it’s designed specifically for a room of this size,” he continues. “This is a mature technology, and the system is built for music and musicians.

“Kirk, for instance, might do a lot of solo work of him singing or writing or playing the piano. Then he might have a 25-voice choral group in there. That’s one of the advantages of electronic architecture. We can give him a 3.5-second reverb time to sound like a cathedral or large church, and it is reproducing the sound in the room with the musicians. It’s not a cheesy sounding spring reverb or post process. It’s real-time, returning the reflected energy to the musicians from walls that are, for example, another 30 feet away and a ceiling 15 feet higher.

“For recording purposes, we want these intimate spaces to capture a tighter, better sound,” he adds. “Now you can get the best of all worlds: Make it tight, medium, huge. It works particularly well for Kirk’s approach to music. He has a rhythmic, pop, hip hop background, but he also likes lush strings, choral groups and other elements that he brings to it. He can record his entire palette of live sounds this way in the studio space with no latency.”

Franklin admits that he has yet to really play with the system and stretch it. The past year was mostly about a big tour and other projects, including producing new gospel artists for his label and inspiring the next generation. He’s spent plenty of time in the studio, as evidenced by the writing/pre-production videos on his website (they’re good!), and he’s gearing up to enter an album cycle. He is a driven and energetic man by nature, even more so once he gets with people and starts making music.

His musical world has always been about collaboration, and he’s recorded and performed with everybody from CeCe Winans and David Foster, to Jill Scott and Pharrell. A track he did with Kanye West caused a ruckus with part of his fan base; it didn’t even enter his mind that people might be upset.

“I’m always amazed at why they come to me,” he says, humbly. “I think that the ingredients of the kind of music that I do can really speak to the soul of a person. Talking about drugs or money or girls or things—that’s not really medicine for the soul. The soul needs more. And I think that the kind of music that God has called me to do speaks to those areas. In deeper ways.

“You would be blown away at how many people I’ve met who are aware of my music, where I would have never thought they listened to my music,” he continues. “At the same time I have to be aware of what’s happening sonically and aesthetically in the world of pop music. The mix. The sounds of the kicks and snares. Audible aesthetics change so much. It’s important to be aware and pay attention to your craft. So I hope that I bring that to the table, as well.

“As a kid, I was really not inspired as much by gospel music as I was by pop music. The Commodores, Elton John, Stevie Wonder, and believe it or not, The Carpenters. Billy Joel’s This Is My Life. In the ’70s, even white music felt black. Very soulful. Moving into the ’80s, there was a lot of music out of England that had soul. You listen to the Eurythmics, David Bowie, Duran Duran, Peter Gabriel. I was inspired by all of that music.

“Then when I played at church, I brought in a lot of the music that I heard on the radio. All my school-age friends liked me because I could play Jackson 5 songs, or Elton John songs. I was always moving with that music and maneuvering with that style and feel. That was the music that moved me.”

With the long-dreamed-of studio base in place, surrounded by friends and family and the creative spirit, Kirk Franklin seems ready to draw the curtains and open to Act II of his musical life. Friends and family, a community of support, a hometown on the rise—all of these things are important to him. Very important. Which leads back to the studio name, Uncle Jessie’s Kitchen.

“I call it Uncle Jessie’s Kitchen because Jessie Hurst was a childhood friend of mine since age 14,” Franklin says. “He was my manager and road manager at the start of my career, and has been the most loyal, integral, kindest friend. I had an accident back in 1996. I don’t remember it, but I was told that I walked off into a hole in the stage, into a pit, and I was in a coma for a couple weeks. The person who found me, and then jumped into the pit to pull me out, was Jessie.

“Well, he got real sick about six years ago, and he knew that dream of mine from the beginning, to have a studio. He’s still with us, but he’s not able to be a part of my career now. I just wanted him to be able to continue to live the dream with me. That’s why we call it Uncle Jessie’s Kitchen.”