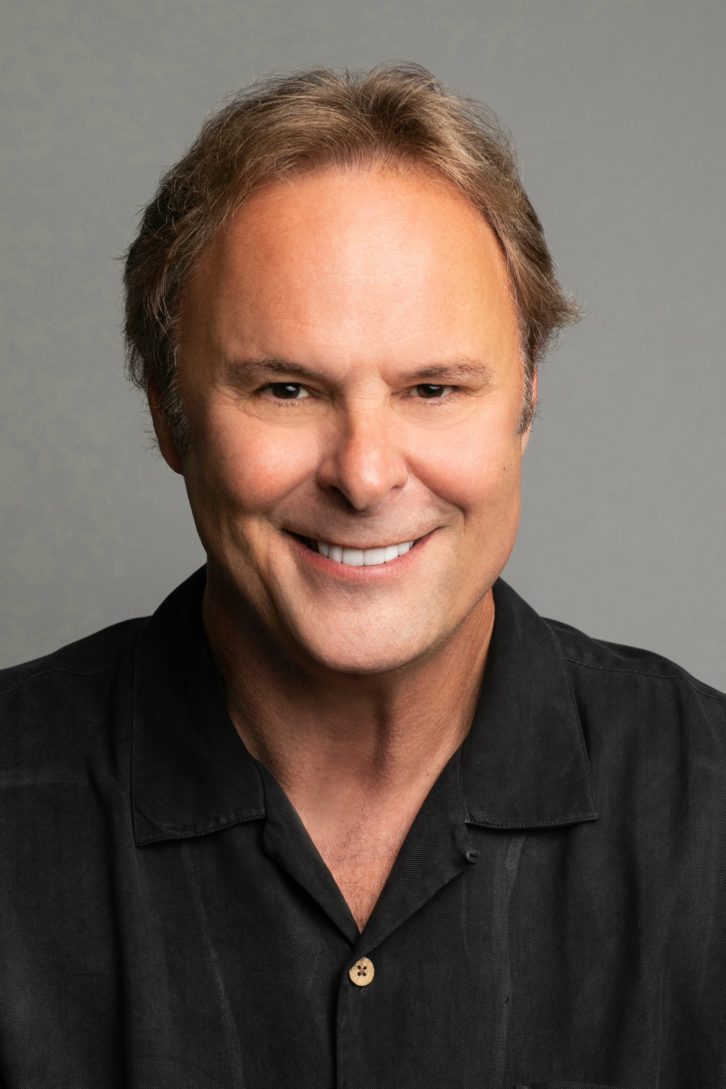

For the past three decades, Scott Hendricks has had an indelible impact on the “sound” of modern country music. Since his first chart topper with Restless Heart’s “That Rock Won’t Roll” in 1985, Hendricks has produced a staggering 78 Number One country singles and more than 120 Top 10 singles. He’s the producer behind monster hits by John Michael Montgomery, Brooks & Dunn, Trace Adkins, Alan Jackson, Faith Hill, Steve Wariner, Lee Roy Parnell, Jana Kramer, Dan + Shay, Michael Ray and William Michael Morgan, to name a few. Perhaps most notably, his 12-year partnership with Blake Shelton has spanned seven albums, two EPs and 24 Number One hits (and counting).

Hendricks has earned seven awards from the Academy of Country Music, five from the Country Music Association, and an Emmy for his work on the Monday Night Football “All My Rowdy Friends Are Here on Monday Night” theme with Hank Williams, Jr.

When Hendricks isn’t making hits, he’s cultivating emerging country talent: As Executive Vice President of A&R at Warner Nashville, he’s overseen the development of Hunter Hayes, Brett Eldridge, Michael Ray, Dan + Shay and Morgan Evans, among others. And, he’s guided scores of superstar hopefuls as a mentor on NBC’s The Voice.

Hendricks has built a career on taking chances, ever since he left his native Oklahoma in 1978 for the promise of Nashville, armed with a box of demos and a degree in architectural acoustics. Mix sat down with him to learn how that approach has paid off and how he hones in on that elusive hit.

Let’s start way back. You grew up working on a farm, spending 12 hours a day driving a tractor and listening to the radio. Would you say that’s when you realized the power of a hit song?

That was probably where it began subconsciously. Listening to songs over and over all day on the radio while I was plowing fields definitely molded me as I learned what hit songs are supposed to sound like. By definition, a hit song is a song that doesn’t grow old when you listen to it repetitively like I did then. A hit song also has to move the listener in some way, either physically or emotionally. Those early lessons in what makes a hit definitely impact how I think about songs and, now, how I try to identify what is or is not a hit.

You knew you wanted to get into music, but you didn’t know exactly how. When did things change?

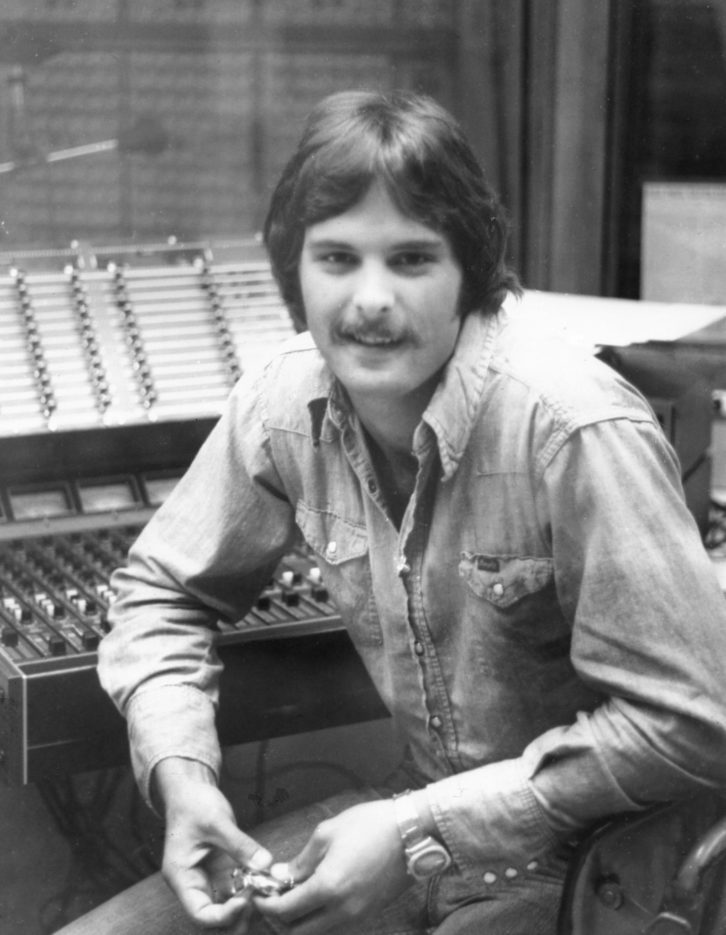

I was at Oklahoma State University. I went with one of my friends who was enrolling in the forestry department; I was just sitting in the waiting room, waiting on him. This was a few days before classes started my freshman year. A gentleman sat down beside me and asked what I wanted to do. I said, “Well, I want to make music, make records.” When he asked me how I was going to do that, I really didn’t have any idea. He said, “You ever thought about working in a recording studio?” I said, “I’ve never seen a recording studio, but that’d be awesome,” and he literally got up and went to a payphone. He made a call, came back, handed me a piece of paper with a name and a number on it and said, “I think I have you a job in a recording studio. Call this guy.”

I did, and that man’s name was Floyd Loftiss, who ran the audio-visual center that was located in the main library on campus. The only thing I really had going for me was enthusiasm, but, for some reason, he hired me to work in that two-track studio, which was two more tracks than I’d ever had before. We’d mainly record lectures and things that went on around on the campus.

Floyd introduced me to Tim DuBois, who also used to work at the audio-visual center years ago but was now teaching accounting at Oklahoma State. Tim and I started writing songs together. We eventually talked Floyd into getting us a four-track, which changed our world. Going from two tracks to four tracks was monumental! We started making demos that we would take to Nashville to play for publishers, most of which were rejected.

Once I graduated with a degree specializing in architectural acoustics, I moved to Nashville full time. I already had a job lined up with a company called Nashville Studio Systems, designing studios and selling studio equipment. While trying to make a sale to Glaser Brothers Studio, I met another Oklahoma State graduate by the name of Ron Treat. Ron was engineering for the biggest producer in country music at that time, Jimmy Bowen, who was also the President of Elektra Records. Ron said, “Why don’t you just come hang out while we record?” I immediately took him up on his offer!

As soon as I got off work from Nashville Studio Systems, I would go to the Glaser Brothers Studio and stay until it closed, which was typically around 1 a.m. I was a sponge—learning everything I could from watching the best musicians in Nashville record iconic albums produced by Jimmy Bowen. Some of the artists making albums during that time were Hank Williams, Jr., Merle Haggard, Conway Twitty and many more.

As excited as I was about making $12,000 per year at Nashville Studio Systems, I quickly realized it was going to take more than that to survive. I went to Belmont University and convinced them they needed to add a course in Architectural Acoustics to their curriculum. That started me on a seven-year part-time teaching job there.

When did you start engineering records yourself?

Once Bowen and Ron decided to move their operation to Sound Stage Studios, Glaser Brothers Studio hired me to replace Ron as one of their staff engineers. Even though I had no formal training, clients evidently liked what I did. I was never very technical. I simply turned knobs until it sounded right to me.

Pretty soon you were mixing Number One records. How did you go from sought-after engineer to sought-after producer?

I became so busy engineering and teaching college in the mornings, I literally had no time left to write songs. Plus, the songs I recorded every day felt so much better than the ones I had written, so I chose to focus on engineering. Simultaneously, Tim DuBois focused on writing songs. He had a batch of songs that he could not get anyone to record, so we decided to record them for fun with some friends we knew, three of which were also Okies. We went into a studio who gave us spec time on the weekends. The band had no name. We simply had a ball recording tracks that we thought no one else in Nashville would understand.

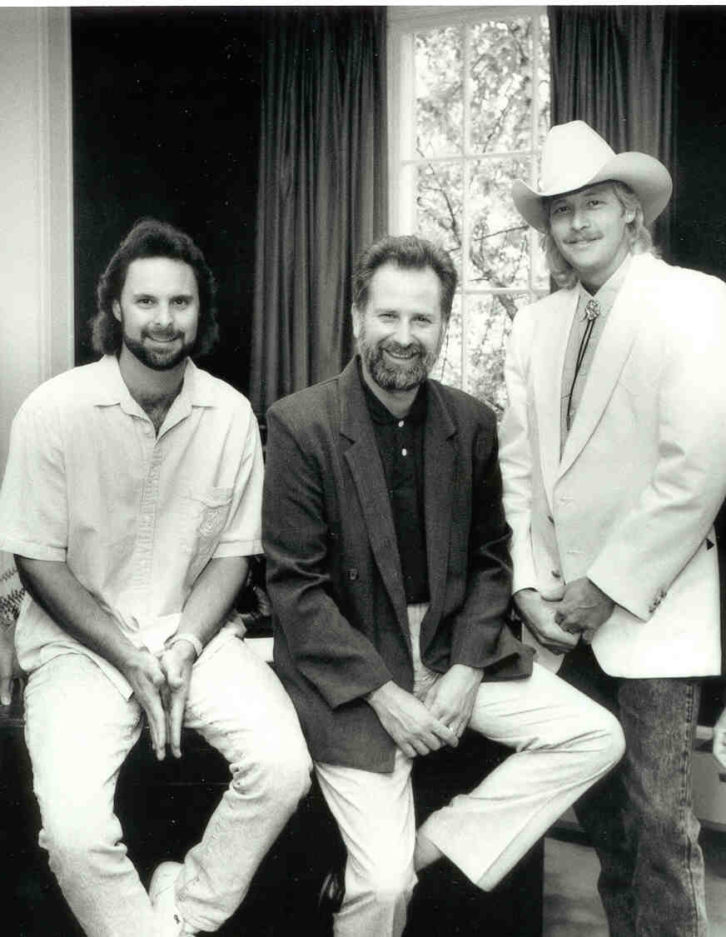

Tim took the final product to Joe Galante at RCA and he signed them to a record deal. Ultimately, they came up with the name Restless Heart, which was as outside of a name for a country band as the songs were at that time for country music. “That Rock Won’t Roll” became our first Number One song at radio. A year later, we released the CMA Song of the Year, “I’ll Still Be Loving You.”

Suddenly, I go from an engineer to engineer/producer. Seven years earlier, I had no idea what a producer was! Once you have one hit as a producer, others tend to want you to produce for them. When Tim opened the Nashville Arista Records office, he wanted me to produce his first act, which was Alan Jackson. A year later, I brought him Ronnie Dunn whom he introduced to Kix Brooks. Within a few months, they became Brooks & Dunn. I ended up producing and engineering several acts on Arista, including Steve Wariner and Lee Roy Parnell, among others. There was a certain point where I had to give up some of the engineering. So I started hiring engineers to track for me and eventually hiring engineers to mix for me.

What was that transition like?

It was really fun in some ways because they did things that I’m not sure I would have done, but I really liked the results. There’s one engineer in particular, a mixing engineer who I’ve now mixed with on countless albums. His name’s Justin Niebank. Justin and I were trained by the same guy.

In the mid- to late-’80s and early ’90s, I engineered many projects with Barry Beckett, who was the leader of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section. Barry had moved to Nashville and auditioned me to become his engineer. I learned so much from Barry. When I got so busy working on all those artists from Arista, I no longer had enough time to continue engineering for Barry, so Justin Niebank moved from Chicago and took my place with him. Since we both were trained by Barry, when Justin started mixing a lot of these records for me, we both kind of thought the same way because of how similarly we were molded.

You worked with such heavy hitters early on. You assisted Jimmy Bowen. Then, Barry Beckett. What have you learned from these greats that you apply today as a producer?

I still constantly think to myself, “What would Barry think about this? How would he have treated this?” I just had such respect for him. Barry was the definition of “feel.” We worked on two-inch tape, and I can’t count how many times I had to cut out a sliver of 1/32 of an inch of two-inch tape to improve the feel. “Pocket” is another word I would say Barry ingrained in my brain.

Having engineered for so many different producers, I learned how they communicate with artists, what works, what doesn’t work. I just absorbed so much of that, so I was prepared when it was my time to sit in the chair and make the decisions, “Should we cut this track again? Do I have enough takes I could edit together? Have we nailed the right tempo, key and feel?” All of those producers that I worked with became a part of my DNA that helps me make those decisions.

In mainstream country, are you operating more in a singles landscape, and how is that different for established artists versus new acts?

Yeah, it’s changed a lot over the years. I miss the days where we would go in and record an album all at one time. I engineered seven Hank Junior albums, and every year we would block off the entire week in the studio, camp out and track the entire album. These days, we typically go in for maybe one or two days and we might track three songs at a time, then we wait until we find three more songs.

It’s changed a lot, and yes, it’s becoming more singles oriented because if you don’t have the singles to drive the records … If you play golf, it’s like the driver. You’ve got to get down the fairway, and you’ve got to have a driver to get down along the fairway. If you’re a new artist, it’s getting to the point to where you need to have a few singles before anyone is interested in buying a whole body of work.

How is Nashville’s evolving identity informing the choices you’re making?

Nashville has changed so much since I’ve been here. Nashville is making all kinds of records. It used to be pretty solely mainstream country, and now we have rock records coming out of here. We have a lot of alternative records coming out of here. We have Christian records being made here. There are a lot of musicians who have gotten out of the craziness of the other recording centers and moved to Nashville. It’s really a much broader musical landscape than it used to be.

It seems like you’ve followed this trajectory where you’ve taken a lot of chances and pivoted to roles you maybe initially didn’t intend to embark on. From where you’re sitting now, what would you tell people aspiring to your career path?

Be open to whatever opportunity presents itself and be the very best you can be when you get that opportunity. Go above and beyond to show whomever it is that you’re working with that you’re worthy of being there.

When I went to run Capitol Records, I was producing a lot of multi-Platinum-selling artists at the time. Somebody said, “You know you can make hit records, but you don’t know about this side of the business.” I was like, “You’re right. I’ve never climbed this mountain. Let me learn about that challenge.” So, I did, and it opened up a lot of new doors in a lot of different areas. Just be open and do your best and hope that it’s good enough.

That can be a difficult thing to measure.

That’s an interesting thing, the psychological part of this industry. It is harder to determine in this industry if you’re good enough to make it or not. If you want to be a pro baseball player, it’s much easier to make that determination, “Can you hit a 95-mile-an-hour fastball or not?” Creative people always wonder, “Do I have what it takes to write a hit song?” Or, “Do I have what it takes to sing one, or play on a record, or engineer a record, or produce a record?” It’s human nature for us to question these things.

I tell people all the time: “If what you are doing is not working, pivot and change.” At one time, I thought I was a really good guitar player, until I met one who was 100 times better than me. And at one time, I thought I was a decent songwriter, until I started getting into the studio and making records where every song was like, “Man, that’s better than any song I’ve written.” So, I just kept refracting to figure it out, “Maybe I’m better at engineering. Maybe I’m better at producing. Maybe I’m better at picking songs and identifying what is a hit song? What is not?”

No one is 100 percent successful. The best baseball players in the world hit less than four out of 10 pitches. Reality is more about striving to have better percentages. You gain confidence by your experience.