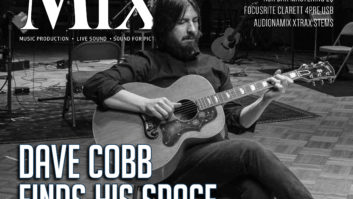

It reads awfully close to an indie film festival screenplay, the story of how producer-engineer Ian Schreier first heard Sarah Shook sing in a small shack turned into a rehearsal space deep in the woods of Chatham County, outside of Raleigh-Durham, N.C. He was there on a weeknight as part of his day job, chief engineer at nearby Manifold Recording.

An intern at the studio, Marco Bianchi, had invited him; he was hoping that Schreier would agree to track “his friend Sarah,” who was getting ready to sing, in the big room back at the studio as part of his internship project. In his six months at Manifold, he was required to do some type of independent record project, and he wanted some quality tracks to play with when he returned home to Italy. Manifold owner Michael Tiemann would donate the world-class, Wes Lachot-designed space, and Schreier would donate his time and talent. That’s how the internships worked.

So there he was, waiting for Sarah Shook & the Devil to finish tuning and start rehearsing. Shook on guitar, joined by pedal steel and an upright bass.

“I can remember being there, drinking a PBR, and Sarah starts singing. I just stopped,” he recalls. “Wait, is this what I think it is? Do I now know what it means when somebody says, ‘They have it. The X factor,’ or whatever. It was a bit rough at that point, sure, and I’m there as part of Mario’s deal, but there was definitely something about her. Something there. An authenticity.”

A couple months later, Shook and her band came into Manifold and cut a quick and dirty seven-song LP, with Schreier tracking. Bianchi took his copy the files home; Schreier and Shook stayed in touch.

And now, six years later, Shook, with her new band the Disarmers and Schreier as producer and engineer, has just released her second full-length, Years, on Bloodshot Records. It hit the Billboard Americana charts in its second week, and it’s received high critical praise across the board. It maintains the raw and sometimes frenetic energy of the band’s debut, Sidelong, while adding a bit of spit and polish. Not much, just a little. The songwriting, the vocal, the arrangements—everything just seems a little richer and fuller. Her voice, whether in a whisper or a scream, sounds more mature, and her phrasing seems more her own.

The Path to Years

Hers is not an overnight success story. That’s six years of working hard and playing hard. Breakups and beers, band members coming and going. Playing strange stages night after night. Writing all the time. She had a pretty good idea of how she wanted her songs to sound, and she had a bona fide musical partner in guitarist Eric Peterson, who had been with her from back in her Devil days.

Schreier and Shook, meanwhile, continued to stay in touch, and a couple years after making the LP they got together and she played him some songs she had been working on. Some she had recorded at home, some on her phone. For the past year it had been mostly her and Peterson playing live, often with a pedal steel player.

Related: Producer/Engineer Ian Schreier, by Tom Kenny, March 4, 2016

“Right away I said, ‘Sarah, you need a band behind you, an absolutely kickass rock band,” Schreier recalls. “’You’re playing country, but it needs to be played with rock and roll intensity, some edge, to bring out the ferocity of these songs.’ Sarah is a punk rocker who likes country music. All the great ones were. Johnny Cash had the punk rock ethos, Waylon Jennings. Things really gelled on that first record when it became clear that’s what was driving the sound.

“Then it wasn’t for another two years that we actually made Sidelong,” he continues. “First she had to find the players, then we had to work out a method. We actually started pre-production without a band—just me, Sarah and Eric. In my head, I started to hear this sort of honky-tonk country with aggressive and powerful drums. The guitars would be country guitars, but with thick twang. Grit and bite to it, but not fuzzed out. I thought that would be a good place to go. And Sarah shared that vision. We made a lot of decisions about the recording before the red light went on.”

It certainly helps that the producer is chief engineer at a top-shelf studio designed for flexibility, a space that can house a 60-piece orchestra or a four-piece rock band with three big booths to spare. But that doesn’t mean that he suffers any less in trying to figure out how to get a great record made at a relatively low cost. He might be able to sneak in early and go home late, but he has to rent the space, too. Guitarist Eric Petersen put forth most of the funds to make Sidelong the way they wanted to make it. Schreier had a contract to engineer, mix and produce, but he waived any producer advance.

“I knew that I wanted to work with her in some capacity,” he says. “She is something special, something unique that doesn’t come around very often. She has that essence of weird that attracts the ear. And she has authenticity. At the time, I didn’t know where any of this was headed.”

But both Schreier and Shook knew that no matter what they did, it would need to involve long and intensive pre-production, rehearsing the songs down to the eighth-note and fine-tuning the arrangements in order to truly take advantage of their time at Manifold. By the time they reached the studio, there was a foundational setup in place that allowed for accidents, those “magic moments,” as Schreier calls them.

“I think a lot of people make a connection that doing a live-ish recording in the studio is just setting up and seeing what you get,” Schreier says. “It needs to be said that doing a recording like this, where budget is an issue, takes just as much time, if not more, than a standard track-overdub-mix method. It just has to be more planned and more carefully thought out before the process starts.”

The planning paid off. Sidelong got a lot of attention, and after a self-release, Bloodshot Records signed the band and re-released it, to even bigger acclaim. Plans started developing for a follow-up, and after some back and forth, Bloodshot agreed to let them once again set up shop at Manifold. Ten days.

Tracking for Years

“Obviously we wanted our sophomore album to be just as good if not better than our first release,” Shook says. “We wanted to put together a ‘kick ass and take names’ kinda deal, and I think we achieved that. Because we track live, we rehearse like crazy before we even get into the studio. That pre-production is intense but totally necessary.

“This is a good group of humans,” she continues. “We get along well, we work and play together well. And there’s an intensity we collectively experience in the studio where we’re all well aware if even one of us f-#*% up, we gotta start all over at the beginning of the song. We’re very present and we’re very much there for each other.”

“We all agreed that there is something that happens when people are playing together in the same space at the same time,” Schreier adds. “Even if it’s rehearsed to death, all it takes is one person hitting a string a little bit differently and it will generate a reaction from another player slightly differently. To me that makes performances exciting.

In order to be efficient, they had to have a plan; in order to make music, they had to remain flexible. Schreier’s knowledge of the room, his home these past ten years, allowed for both, and it began with the setup.

“Drums were in the big booth with the doors open,” Schreier explains. “We wanted everyone together, breathing the same air, but the doors allowed me to use gain control of the drums into the room mics. The guitar and the steel are out in the room and facing the drums, their amps, too.

“Sarah and her guitar are near the center of the room in a gobo booth that I put together, with a lid on it,” he continues. “We wanted to keep the guitar tracking, but we’re not trying to get the lead vocal here. She’s playing rhythm guitar, an arch-top hollow-body, played through and early ’60s Epiphone. Two controls. It sounds spectacular. The only thing isolated is the upright bass. He was in a booth, with line of sight, and the door cracked. A lot of those bass tracks were live and miked, with sometimes a DI and reamp.

“So that I could have flexibility in the mix, I did a standard miking of the kit, with mostly Josephsons on snare and toms, but the vast majority of the sound you hear is from the mono overhead in front of the drum, a Neumann U47, and the room mics, Sanken TL100Ks.

“On the guitar amps, I used a Coles ribbon mic and a Schoeps condenser. The ribbon is very friendly to guitars and will take EQ well. The Schoeps give me exactly what is coming out of the amp, with a warm glow around them. It’s a great combination. Plus, a lot of the guitar sound is coming from that pair of room mics. Pulling up those two faders takes it from a recording and makes it a record.”

Things changed slightly for Shook’s vocal chain between records, partly because Schreier was more in touch with her voice. And partly because Shook was too. “I spent some time with our first album before we went into Manifold to record Years,” Shook says. “I wanted more control of my vocals, more nuance, more interesting cadence. I feel like the overall sound of the record is bigger, warmer, more golden this time, with a lot of space to it. Definitely warmth and depth.”

Related: Profile: Manifold Recording, by Tom Kenny, May 1, 2011

On Sidelong, Shook sang into a Telefunken C12. This time Schreier wanted to experiment, having learned more about the fierce tenderness of her voice and its rich, more filled-out timbre. So he put her back in the gobo, in the middle of the big room, and put up a combination that he‘d never tried before but thought might work—a Shure SM7B and a Brauner VMX.

“Her voice has such different sounds and different ranges,” Schreier says. “The SM7 does its thing and you can scream into it and it’s awesome. The Brauner can be either solid-state or tube and it’s super-great-fantastic top-end condenser. There’s nothing better than a great condenser mic on omni in a big room Then into DW Fearn preamps; I like those on her voice. And the DW Fearn compressor, too. It’s a matter of dealing with the enormous gain change between her singing low and soft to loud and rocking. At one point I set up two completely different gain stages. I could then place her vocals a little more specifically on this record.”

Years was tracked through the API Vision to Pro Tools, with playback from Dynaudio M4S mains and ATC SCM25 nearfields. For mixing, he went next door to the Harrison-equipped control room, partially for the ease and feel of the automation, but mainly because he prefers to mix on his favorite speakers, the Guzauski-Swist GS3As. Most of the sounds, he maintains, were baked in from the tracking, from the movement of sound in air. Any effects employed were mainly for fixes or tails. He did use more compression this time through.

Now, two records in, Schreier and Shook have put together a pretty effective process that allows them to make records, in today’s climate, the way they want to. And they’ve learned a few things along the way, too.

“You have to be prepared, 110 percent,” Shook says. “But above all else, you have to write damn good songs. The songs are the key components of the best magic ever to be eked out of a board.”