The Beatles’ music is ingrained in modern culture. Fans know every note of every recording—and the mixes of those recordings—created 50 years ago by producer Sir George Martin and engineers Norman Smith, Geoff Emerick, Ken Scott and Phil McDonald. If either were to change noticeably, fans would immediately raise a red flag. They wouldn’t be The Beatles’ records as we all know them.

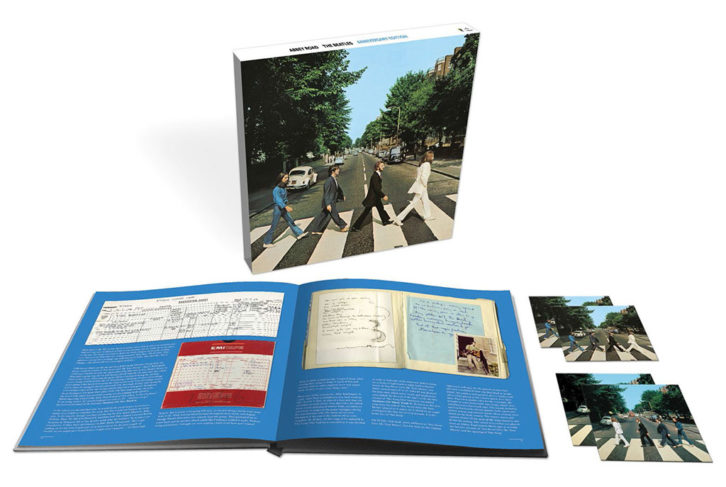

That has been the challenge facing Grammy–winning reissue producer Giles Martin (George’s son), Grammy–winning mix engineer Sam Okell and the rest of the team behind Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UME’s 50th anniversary reissues of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band in 2017, The Beatles (aka The White Album) in 2018, and Abbey Road in 2019. Each deluxe set contains discs of new stereo mixes created by Martin and Okell, along with 5.1 surround (and, for Abbey Road, Dolby Atmos) mixes and discs full of session outtakes and demos.

The first step in the process is for Martin to decide whether there is even any improvement to be made, if he feels he can mix the album in a way that makes it sound more relevant, clear and revealing than the original version. Martin, who began working with Beatles material in the mid-1990s while in his 20s (“acting as my dad’s ears”) on the Beatles Anthology projects, and later winning two Grammy Awards for his and his father’s remixed soundtrack for the Cirque du Soleil LOVE album, notes, “I always bear in mind, ‘Why would I want to hear a remix of an album I love?’”

Once it has been decided to proceed, the next step is to study existing outtake material from the original 4- and 8-track masters. When the Martins and engineer Paul Hicks began the LOVE soundtrack, built out of pieces of individual tracks from different Beatles songs, Giles Martin realized there were no digital backups of the Beatles multitrack reels. So Abbey Road Studios engineer Matthew Cocker, who joined the facility in 1988, began a long-term project of creating digital backups of each reel, at 192kHz/24-bit, using Benchmark A/D converters for Pepper and Prism Sound converters for the later projects.

Photo: Alex Lake

While Cocker’s transfers were of all individual reels, strictly for archival purposes, his work for Beatles reissue projects requires a further step. For Beatles recordings made on 4- and 8-track, due to the limitations of the medium, George Martin would often fill up the first four tracks of one reel, mix down that material onto one or two tracks on a new reel, and add overdubs. Final stereo mixes of the day were then made from the latest reel. “Because it’s The Beatles, each of those reels have been kept,” Cocker says.

When creating new mixes, however, Giles Martin and Okell wanted to take advantage of the discrete, individual track material, drawing on the original raw performance of an instrument on an earlier reel, not the submix of combined instruments found on a later reel. So Cocker would take a second transfer pass, this time synching each reel for a given song. It’s not as simple as “lining things up in Pro Tools.”

“You can slide things on a timeline, but they won’t be phase-accurate,” Martin explains. “And we don’t want to digitally stretch anything, because we want to keep it pure.” Adds mastering engineer Miles Showell: “Analog tape never plays at the same speed twice. Every time you run it, it’s different. Even if you cue up all the tape machines and hit Go at the same time, they will drift out of sync.”

So Cocker uses two special tools to accomplish the task: his ears and a manual vari-speed control connected to the playback tape machine (a Studer A80 from the 1970s for 4-track and a Studer A820 for 8-track). Keeping the original stereo master as a reference, Cocker transfers in the first multitrack reel. He will then find a start point—say, the fourth beat of the song—and cue the tape machine of the following reel to that point, then hit Play at the right moment.

Photo: Kirstin Prisk

To keep sync, he pans a mono mix of the first reel’s content hard left, then pans a mono mix of the new reel’s content hard right. “Then, listening in headphones, you literally just ride the vari-speed knob and keep the image central in your headphones,” he explains. “That means you’ve got it phasing so that there’s cancellation in the middle. It takes a little rehearsal, but you get used to it.”

Martin prefers to work from the synched multitracks instead of the final 4-track reel, not just for stylistic reasons, but also for audio quality. “If you think about it, mastering engineers remastering these albums are working from my dad’s original 2-track stereo reels, which have been taken out of the tape library and played something like 50 or 60 times over 50 years. We’re working from a much earlier source—and a much better source.”

And EMI’s own EMITape was of such high quality—and offered plenty of tape width (and, thus, high fluxivity) for each of four tracks on a 1-inch tape—that “I’ve never had to bake a Beatles tape to get it to play. EMITape is beautifully preserved, it just sounds so good,” Martin says.

Notes Showell: “You put those multitracks up, and you hear content you never even knew existed, and at incredible detail. So Giles and Sam’s approach allows them to strip away any kind of noise that may have crept in, to give them a very pure recording in their new mix.”

GIVE IT A LISTEN

Prior to synching—and as much as a year prior to release—a pair of expert Beatles historians/researchers listens to the raw session tapes and other materials to look for candidates for bonus material. The two are former EMI catalog VP Mike Heatley, who joined EMI in 1973 as an employee at one of the company’s HMV record stores and went on to handle Beatles projects until his retirement, and former BBC Radio producer Kevin Howlett, known originally for his work in the early 1980s on the “Beatles at the Beeb” series and for writing detailed liner and production notes for a number of Beatles projects.

“We’re listening for material that hasn’t been made available before, that we feel adds value to any anniversary edition,” Heatley states, noting that not everything heard should be released, for a variety of reasons, not just quality of the recording. The goal is to provide a peek into The Beatles’ and George Martin’s process, often starting with an early or significant take from the first day of tracking for each song on the final album.

“People know The Beatles’ music as great art,” Martin says. “So it’s kind of like being a doctor, going into a very fit body, and the more you open it up, the more you see and learn. The idea is that we want people to be able to get as close as they can to the recording sessions as possible. And that means including chatter, including the humor, which helps you realize this music is made by four people in a room.”

Early versions, such as the raw “Sgt. Pepper” title track Take 9, with just guitar, drums and vocals—no bass or horn overdubs yet—give listeners a sense of how the recording sounded to the band in the studio as they were beginning to create it. “If you listen to just the backing track of George’s ‘Here Comes the Sun,’” says Howlett, “it’s the core of the song, just Paul, George and Ringo playing bass, acoustic guitar and drums. And then you hear the finished result, and you realize just what brilliant record makers they were.”

Cocker’s transfer activities also occasionally revealed hidden gems found at the end of reels that had been marked as having been wiped for reuse, but which contained early takes or versions of songs previously unknown to historians.

For instance, at the end of one “wiped” White Album reel, he encountered a previously unheard rehearsal of the fast, single version of “Revolution,” recorded the night before the proper recording was made—and prior to engineer Geoff Emerick’s creating the song’s trademark distorted guitar sounds. Lennon’s and Harrison’s guitars are heard as clean electrics. At the end of another reel was an early take of Lennon’s ballad to his mother, “Julia,” in which he can be heard discussing with producer Martin whether to play the song sitting versus standing, finding it difficult to do the latter. “Not only do you feel you’re in the studio with John and George Martin as ‘Julia’ is being rehearsed,” Howlett says, “but it’s also wonderful to hear, simply because it’s great! It’s a beautiful performance.”

Photo: Alex Lake

Once Howlett and Heatley have compiled lists of their recommendations for Martin, the producer will have a listen, even sometimes returning to the reels himself to find other takes he might have remembered. “We leave no stone unturned,” he states. The list is eventually whittled down and then presented to Apple Corps’ Jeff Jones and Jonathan Clyde, before the final choices are given to “the Board” to hear—McCartney, Starr, Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison.

Due to time demands, Martin will mix outtake material in his own dedicated room at Abbey Road, while Okell is creating the new stereo mixes in the Studio 3 control room.

STEREO MIXING

The approach to remixing a Beatles album is not simply a matter of copying the original verbatim. Martin and Okell’s goal is to bring fans the record they know—just more of it. “We always think about, ‘How does the music make you feel?’” the producer explains. “’Here Comes the Sun’ should sound beautiful. It should flow over you like a warm bit of sunshine. It’s spiritual. Sgt. Pepper is an album you want to fall into. The White Album is an album to punch you in the face; you realize it’s a visceral record. And Abbey Road is a kind of a hi-fi record, where you want it to just sound beautiful.”

“So if that’s your goal,” he asks, “then how do you get there? Because we don’t really mix albums anymore. We mix individual tracks. But with The Beatles, there’s a feel to their records, which is so recognizable. Partly, I suppose, because they were done so quickly, and they were all mixed in the same room. That doesn’t happen today, where they’re mixed by seven different people in different countries.”

The first step, Okell says, is to indeed copy the original stereo mix as closely as possible, “checking that we’ve got all the right parts and bits and pieces sounding sonically similar, to make sure we don’t get too far away from the way fans know them.”

It is an iterative process, he notes. “We start by just trying some things. And when we put a few mixes together, we realize that we’re going slightly down the wrong road, in that it might be imperceptibly different from the original. Or we do it the other way, and change things too dramatically, and it doesn’t sound like the original. So it’s an iterative process of swinging back and forth.”

In “Here Comes the Sun,” for example, there are woodwinds doubling Harrison’s Moog overdub, something many fans likely have never noticed. “It’s all beautifully balanced in the original record,” Okell says. “So if you bring that out too much, it can change that. It’s nice to be able to notice something new, but you don’t want to make it sound perceptively different.”

In re-creating effects, Okell will always start with true ADT (automatic double-tracking), using a Studer tape machine to introduce proper, authentic delays and doubling techniques that help give the mixes a true Beatles sound.

“It’s something to do with the subtlety of the variation,” Okell notes. “I guess you’re getting a bit of tape compression and coloration on the sound, a tonal coloration, but you’re also getting that continuous variable. And it’s a far more subtle effect on a vocal than just using straight delay.”

Adds Martin, “You don’t want to hear ADT. You just want to have the feel of stereo.”

“But we’re not averse to trying any kind of modern plug-ins,” Okell adds. “Something that might sound great now might, in a few years, sound dated. But I’ve found I’m very willing to experiment. I might start with a Fairchild compressor, but then try some modern thing and see if it gives an edge to the sound that is not distracting, but more interesting.”

Samples are never used, Martin notes. “I only have one rule for myself: I don’t use any samples, and I don’t tune them. Do nothing to the performance. We never bolster Ringo’s drums with samples, because then it wouldn’t be Ringo.”

The use of original gear is, of course, one of the advantages of doing the work at the studio in which The Beatles made their records. The gear is all there, Okell notes, though “we use them less and less because the sound on tape is already there. They were used during recording. We find we don’t need to double-process.”

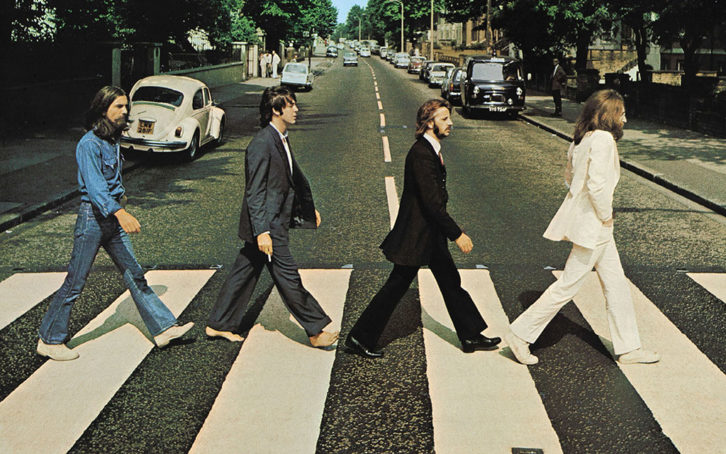

Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UME

Okell will typically mix (or pass some material through) one of the original EMI-built REDD tube consoles, even for Abbey Road, which was recorded on EMI’s then-new TG transistorized console. “Geoff Emerick wasn’t a fan of that desk. He famously said that he felt he couldn’t get some of the crunch, the distortion he had gotten on previous records.”

For reverb, Okell will make use of the original Studio 2 echo chamber, which, he says, “is just fantastic on drums and guitars. Anything that calls for that short, roomy space around things. I might also use a UAD plate plug-in or an Abbey Road plate emulation. We set up some blind tests with some real reverbs and some plug-ins and A/B’d them, particularly on something crucial, like the vocal reverb on ‘Because,’ which ended up being a UAD plate plug-in.”

Okell has some other favorite plug-ins, including some from Waves Audio others from Universal Audio. But a favorite is the FabFilter Pro-Q 3 Equalizer. “We have quite a lot of detail work for which FabFilter is excellent,” he says. “You can have as many points as you want, just a half-dB here or there. It can help take the honk out of the middle of a vocal or add a bit of presence. FabFilter is just a really versatile and good-sounding EQ for that.”

For McCartney’s basses, both his Hofner and Rickenbacker, Okell will sometimes use the studio’s Altec RS-124 compressors or a Fairchild, “and sometimes a modern Waves compressor, which will give it a harder attack. Something like that, you might use subtly in a mix.”

A MODERN, CLASSIC SOUND

As part of their mixing approach, Martin and Okell sought to provide a sound that was somewhat more contemporary, more what listeners expect today, while staying mindful of how fans know these specific recordings. Key to this is the design of the stereo picture.

“A lot of what we hear on earlier records [such as Pepper] has to do with the way things were done then, where maybe vocals aren’t centered,” Okell notes. By taking advantage of syncing the step-by-step 4-track reels, the instruments could often be separated out in the stereo image, though even that had to be done with care.

“We always try to put the bass and drums in the center,” as modern records have, Martin explains. “But bass in the center, on ‘With a Little Help From My Friends,’ affected Ringo’s voice. Sam put it to the side, and he was right. With the bass in the same position as him, Ringo no longer sounded lonely.” A similar issue occurred with McCartney’s voice on “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” when placing drums in the center “actually made Paul’s voice sound slightly distorted.” The drums were panned to the side.

Okell also now spreads Starr’s drums into stereo, by using a simple “tab to transient” in Pro Tools to identify individual drum kit hits/instruments and placing them on their own tracks. “By separating the different drums onto their own tracks, we can apply discrete processing [EQ and compression] or panning to a kick or snare or a tom,” he explains.

Stereo spreading of the drums is also facilitated by using ADT, for very close-sounding doubling of drums to trick the ear into hearing early reflections and giving the impression of a wider sound source, Okell notes. “This is particularly effective on higher frequencies, which is why you notice the cymbals especially.”

Another important tool Okell will use is reamping—placing a speaker at one end of a studio live room, playing back a monophonic-recorded track, such as strings or drums, and re-recording them with multi-microphone arrays placed in the center or back of the room.

“Most of my father’s strings recordings on Beatles sessions are in mono,” Martin notes. “So if you want to make that stereo, over at Abbey Road, we’ve got the very rooms in which these instruments were recorded, so we can just mike up the room, and it gives us a stereo feel, and still reproducing the character of the room in which they were recorded.” (Studio 1 for strings or Studios 2 or 3 for band instruments.) “The speaker is actually facing away from the mic, so it’s reflecting against the wall,” typically a large Bowers & Wilkins unit (“the big spaceships,” he says).

Martin and Okell will often use bus compression, which listeners have sometimes noted makes Starr’s drums louder. “It’s so easy with Beatles stuff to use bus compression to get the sound. It’s something that always helps good bands,” Okell says. “With The White Album, we did it, and I said to Sam, ‘We’re cheating.’ We had The Beatles’ Altec compressors applied, and I took them off. And we went and remixed everything again. We were using the bus compression to hit people in the face. And we wanted the individual Beatles to hit them in the face in the room.”

For session outtake material, Martin (who often mixes those himself, while Okell addresses the album stereo remix) keeps it simple, with essentially no processing. “There’s a deliberate ‘anti-mix,’ because I want people to hear the 4-track tape, without effects,” he explains. “I try and do everything cleared up, so you can just hear what’s on tape. And I do it very quickly, with very few rides. I’ll do some panning, but that’s it. It should feel immediate, like you’ve got a Beatles tape machine at home, and you’re hearing the tape. It’s very important to me that there’s a differential between the finished record and the outtakes.”

SURROUND MIXING

Once Okell has completed his stereo mix, he moves on to creating 5.1 surround and, for Pepper and Abbey Road, Dolby Atmos mixes (the Atmos mix for Pepper was not included in the super deluxe set but was heard in theaters for the album’s 50th anniversary). Abbey Road’s Atmos mixing room was completed in 2017, Pepper being its first mix, recording, as Martin prefers, to 8-track tape.

While Atmos is known for its ability to send sound sources flying around the room, that’s not its purpose for Beatles music, Martin notes. “Our goal is to get you closer to the performance,” he says. “It’s to get it so you feel like you’re immersed in the studio with the band. The closer you get to that performance of a song you love, the more it will resonate with you and touch you more. And immersive audio can let you do that.”

Okell has no template for creating the immersive mixes. Instead, starting with the finished stereo mix, “I begin looking at which instruments in a song we can ‘peel away’ from the front dominant sound stage, to heighten the listening experience without deconstructing it. For instance, does a rhythm guitar part work well when panned half rear, or does it just sound distracting and disconnected from the bed of the music? Our goal is to bring out all the details and nuances of the arrangement and allow them to breathe in the 3D world, but without the song sounding deconstructed.”

Martin’s preference is to place the main band rhythm and main vocals up front, something he says is rooted in The Beatles’ early recordings. “They worked in a mono format, so you have everything in the center. I like the idea of there being a strong central point, which is often indeed vocals, drums and bass. And then a cluster of ambience and sound around that.”

Okell relies on many of the same tools used to build the stereo mixes, most notably ADT and re-amping, the latter to further reproduce the sound of the studio in which the Fabs did the work. “We often use ADT effects to create fake double [triple or quadruple] tracks to pan into the 3D field which mimic early reflections our ears are used to hearing in a real acoustic environment, as sounds bounce off the walls,” he explains.

Only in the case of specific instruments or effects “will we feel we have license to actively pan around the 3D field,” he continues. “Thankfully, The Beatles used this effect in their stereo mixes [most notably on Pepper], so we feel there is some precedent for using this in the Atmos mix.”

There are limits, Martin notes: “You don’t really want things moving around constantly, because it would just drive you mad. You should be listening to the song, not the mix. The goal is the creation of warmth and surround. It doesn’t have to be consistently surround. You don’t have to be always wide or always surrounded. And that’s a mistake I think some people can fall into, because that’s not how we listen. That’s not how the world is. There’s variation.”

On Abbey Road, a listen to the three-part vocal harmonies on Lennon’s “Because” is an exceptional experience. “It’s the three boys all singing onto one track; and they did that three times,” Martin says. “And then we also ADT’d those to create even more width. So it’s three people singing three times, but it’s like a choir.”

The best thing about spatial audio, Martin adds, “is that people can discover a new world. They can hear instruments they didn’t hear before, because they’ve been hidden by compression or by positioning. So it’s up to the listener to find out what they can spot and what they love.”

MASTERING: VINYL, STREAMING, BLU-RAY

The final step, of course, is mastering, performed at Abbey Road by Miles Showell. A relative newcomer to the studio, having arrived in January 2013 and replacing his predecessor, who had the job for 48 years, is not a staff engineer. He has something of a joint venture with the studio, using much of his own equipment, set up in Room 30, one of the rooms in the original house, facing the legendary crosswalk. His first Beatles project was Martin’s 2015 remix of The Beatles’ 1 album, with Pepper following 18 months later.

Though he has some plug-ins, Showell prefers to use analog gear. “My go-to equalizer is a Sontec [MEP 250EX Parametric Equalizer], which is handmade by a guy in Virginia, who builds them on his kitchen table,” he says. He also has a Prism Masalec EQ, a favorite of Martin’s, and a Manley Labs Massive Passive Stereo EQ, which he applies typically for midrange content. His favorite compressor is a handmade re-creation of a Fairchild 670, built by a friend in England at Analog Tube. “He uses all original components and builds them the way Fairchild did, with all point-to-point wiring. There are no printed circuit boards. It takes him 80 hours to build one.”

His disc cutting lathe is a customized, restored Neumann VMS-80. “When I found it, it was in a pile of very broken bits and looking very sad for itself. I had it tweaked to my specifications.”

Showell’s process with Martin and Okell is also an iterative one, as is most of the steps of the process. “I’m not getting stuff that needs a huge amount of work,” he notes. “Ninety percent of what needs to be done has been done by Sam before it gets to me. I’m just doing a dB here or half a dB there, maybe a bit of very gentle compression with my tube compressor.”

Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd./Capitol/UME

Each pass returns to Martin and Okell, who will hear his adjustments and then build those changes into their mix and return it to Showell for another pass. “Ultimately, they want to present something to me that I do as little as possible to,” he explains, “because every piece of kit I’m putting in the signal path alters the sound to an extent. You have to think to yourself, ‘Is what I’m gaining by having this in the circuit worth having it in, for the degradation it causes?’ You want to keep it as pure as possible.”

Showell will prepare one pass with a small amount of digital limiting for streaming services and CD. But he’ll also capture a completely clean pass, without limiting, for Blu-ray (5.1, Atmos) and vinyl. “The Blu-ray is 96 kHz, 24 bit, with no limiting, and I’ll cut the vinyl the same,” he notes. “Ultimately, there’s only so much level you can cut to a record because it just distorts, and it’s too loud. And full-scale digital audio, peaking up to zero on the digital meter, that’s too loud to cut on anything. You have to pull it back.”

His Beatles vinyl is created using half-speed mastering, something at which Showell excels. Discs are cut at 16-2/3 rpm, instead of 33-1/3 rpm, with the master playing back at half the normal speed.

“If you think about it, a tambourine might have a 15kHz component,” he explains. “So in order to cut that at normal speed, the recording stylus has to vibrate at 15,000 times a second. The head can get quite stressed trying to cut all that information. If you halve the playback speed of the source and halve the disc-cutting lathe, you’re effectively turning that 15 kHz to 7.5 kHz, kinda high-mid, which is much easier for the system to cut. You’re not pushing it to its limits, so you get more headroom, much cleaner-sounding high-frequency information. Beautiful, clean top end, and much more defined stereo imaging. And with a very good pressing—as Beatles releases have—and a very good turntable with a good cartridge, you’ve ultimately got a wider range than you would have on a CD.”

A MEANINGFUL LEGACY

Though he is well-known as a producer in his own right, Martin feels incredibly privileged to follow in his father’s footsteps in presenting The Beatles’ music in the best manner possible, both historically and aurally. “It’s a bit like someone’s giving you a beautiful box full of amazing chocolates, and the first thing you want to do is just offer everyone one,” he laughs. “I’m just a pathway through to letting other people into the door to give it a listen.”

With all of its richness, the idea of the new mixes remains the same: Give Beatles fans the sound they knew—just more of it. “If somebody listens,” notes Okell, “and tells me, ‘Well, I can’t tell a lot of difference,’ then I’m perfectly happy with that.”

Howlett, the historian, sums it up nicely: “I think people in the future will be just as interested as we are now as to how these recordings could be made with this equipment. Maybe in 50 years’ time they’ll be just as fascinated to know how this was done a hundred years ago.”