In 2001, Ron Murphy, the engineer responsible for mastering some of Motown’s greatest records and cutting the ultra-hot vinyl that helped define the sound of Detroit techno, told the Detroit Metro Times: “Cutting is not about music. You’ve got to love records.”

Third Man Mastering loves records. The facility, the latest in Jack White’s ventures aimed at elevating Third Man’s presence in his hometown, joins a retail store-slash-performance-venue and a vinyl pressing plant at the label’s sprawling music hub in Detroit’s revitalized Cass Corridor.

The studio represents a new chapter in the city’s music story. “Detroit—and Michigan—had been without any vinyl mastering since 2008, when Murphy passed away,” says Ben Blackwell, Third Man’s cofounder and archivist. “When the local techno artists lost the ability to go and sit in on a cutting session, to hear from someone who’d been cutting since the ’60s, they lost a step to the artists in Berlin and London who still had that access.”

Third Man Mastering plans to fill that gap. The facility offers analog and digital mastering for any format, including vinyl, CD, cassette and streaming. Its services include tape transfers and lacquer cutting, including production masters, reference discs and one-off dub plates.

To run the studio, White tapped veteran engineers Bill Skibbe and Warren Defever. Skibbe is a studio owner and gear designer who helped build Steve Albini’s Electrical Audio in Chicago; he recorded and mixed White’s album Boarding House Reach and albums by White’s bands the Dead Weather and The Raconteurs, along with projects by The Kills, Fiery Furnaces, Breeders, Jon Spencer and Boss Hog. Defever, a musician and producer known for his large body of work as His Name Is Alive on the 4AD label, has produced and engineered projects by The Stooges, The Gories, Low, Yoko Ono, the Von Bondies, Ida and Sun Ra.

After 25 years tracking and mixing, Skibbe and Defever were both looking forward to bringing their recording perspectives to mastering. “One of the things that we bring to the table that’s a little different than other places is we really do have a vast experience of recording records,” Defever says. “Between the two of us, we’ve done over a thousand records. We’ve had the experience of sending a thousand records to other mastering people. So I think that we have an insight into what the artist is intending.”

“It’s the final stage of creativity, and it’s the first stage of production,” adds Skibbe. “Just coming from being in bands and then producing records for so long, I think we’re just in the trenches with everybody. I feel sympathetic when a band sends me a record. I know exactly what they went through to finish that thing, and what they’re hoping to get out of it in the end.”

The studio opened to the public in January, but Defever and Skibbe have been mastering Third Man label projects there for two years. “My wife and I had Key Club Studio in Benton Harbor, just on the other side of the state,” says Skibbe. “A couple years ago, Jack said, ‘Hey, I’ve got this pressing plant and the mastering studio that we’re building. What do you think?’ I thought, ‘Wow, you’re gonna turn me loose on the lathe and I get to have a mastering studio? Great, sounds awesome.’”

Third Man is not a typical mastering studio. “Third Man does a lot of live-to-disk recording down in Nashville. So the original idea of the setup of this room was to get a lathe and then do live-to-disk recording,” says Skibbe. “As part of the deal to get the lathe, they had to take a whole mastering studio’s worth of gear. That put the seed in everybody’s mind that we could be doing this right out of the plant: mastering and cutting lacquers, mastering records.”

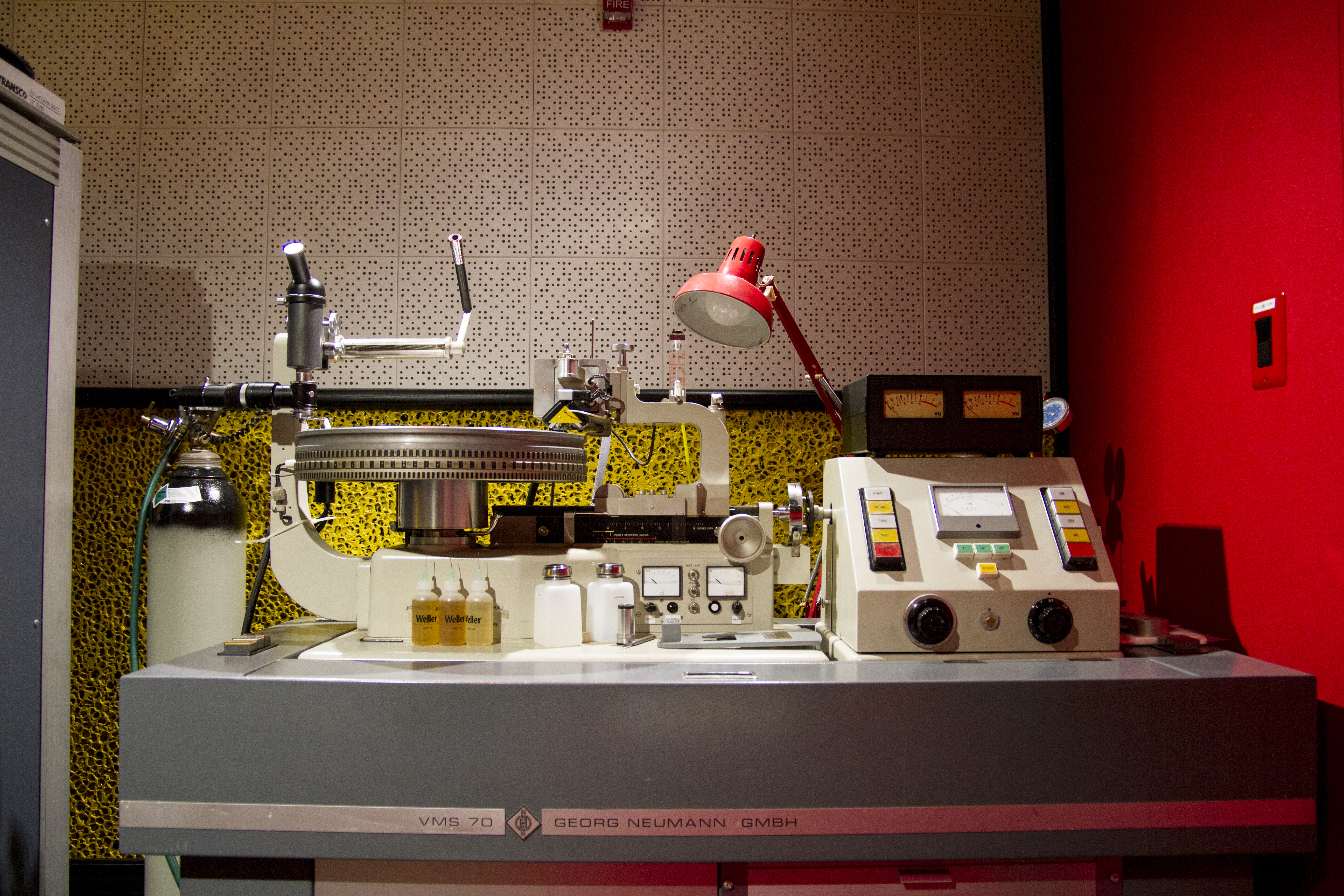

The Neumann VMS70 cutting lathe—the only lathe in the city—is complemented by a custom Manley transfer console, a Neve 5088, Studer tape machines and gear by Esoteric, Dangerous, Sontec, Maselec and Burl; monitors are Genelec 1037s and custom Atomic SixTens. The equipment was purchased as a complete package from SAE Mastering when owner Roger Siebel retired.

“It was funny because I had used Roger a lot over the years as a mastering engineer, so I knew his facility,” Skibbe says. “I didn’t know what I was walking into; Jack just said to me, ‘Hey, you want to come over and record something and then take a look at the studio?’ I came in and I was like, ‘Oh my God. They’ve got Roger’s setup. This is amazing.’

“We custom-tailored it after we got it here,” he adds. “We got rid of some things and bought some other stuff and integrated a focused dream scenario for analog gear. We do analog captures and we process digitally, sometimes. We use a combination of both, but we always run through the analog.”

Once the lathe was set up (with help from Chicago Mastering Service’s Bob Weston, Capitol’s Ron McMaster and Welcome to 1979’s Cameron Henry), the studio was ready to rock. “As soon we had gone through our preliminary phase of getting it calibrated and cutting our teeth on cutting, we had an endless stream of things coming through the plant,” says Skibbe.

Most of Third Man Mastering’s work falls into three categories: label projects, independent mastering clients and clients of the pressing plant next door. The studio also does restoration, including vinyl re-issues from Chess Records, Sun Records and Motown. “Third Man does tons of reissues from the ’20s to the ’50s; all kinds of crackly stuff,” says Defever. “We’re getting sources from all over, from as far back as recording goes.”

The studio offers seamless mastering and pressing, which lets Skibbe and Defever better integrate quality control and production, but they’re quick to point out that they are not exclusive to the plant. “We master for digital as well as vinyl,” says Skibbe. “Because Third Man has such a strong analog vibe, we wanted to make sure that we’re independent from the pressing plant.”

That said, having a mastering studio directly attached to a pressing plant has its benefits. “We get to cut lacquers and then have a test pressing delivered to us in a few days. One of the great things about working directly with the plant is we receive a lot of files that we just cut a lacquer for and get pressed here, so we can hear all the other mastering studios’ work,” says Defever. “We get projects sent in from Bob Ludwig or Bernie Grundman, or anybody great, and it’s always amazing.”

“Sometimes a project comes in from a mastering engineer who’s already prepped it for vinyl production, so we’re cutting it as a straight cut, knowing that they’ve already done all the elliptical equalization and taken care of the top end properly so it comes in ready to go, leveled out, and our levels are all set,” adds Skibbe. “That’s an interesting thing to see where they’re putting their frequency stops and how they’re treating it for cuts.”

Third Man’s plant tours, concerts, live recordings and other public-facing events bring visibility to production processes that are traditionally invisible. It’s all part of an effort to forge a deeper connection to music and music making—for artists, producers and fans alike.

“We have people coming through all the time,” Skibbe says. “We were hanging out with Nigel Godrich a couple weeks ago, who came through to see the studio. Every time somebody plays in town, they come through the place. We’ve recorded a lot of records live to disk in here. We have great shows out front and we have the pressing plant. It’s really important, I think, to Detroit. And it’s super fun to be a part of that.”

“Having mastering, both vinyl and digital, open to the artists of the city, it just makes them smarter and better at their craft,” says Blackwell. “Having access to all of the industry components of the music industry, your turnaround times decrease, your shipping costs go down—it benefits everyone, regardless of genre or pressing quantity or any qualifiers.”

“When I was doing music, there wasn’t a mastering studio in Detroit for 20 years. I would always go to New York or L.A. or London,” says Defever. “And now, there’s a world-class facility in Detroit.”

“Being in Detroit, there’s the legend of Ron Murphy, who did all of the Motown stuff and then did all of the Detroit techno stuff,” says Skibbe. “You’d go to his house and he’d cut your record in his garage, and you’d hang out with him and he’d be fiddling around with stuff, and it’s kind of the same idea. And so, we’re standing in the shadow of Ron.”