Nicole Kidman in The Invasion

Photo Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures

Effects mixer Gregg Rudloff wants to make you feel uneasy. Granted, that’s not usually the assignment for the two-time Oscar winner (for Glory and The Matrix) and four-time nominee (most recently for Letters From Iwo Jim a, profiled in the January 2007 Mix). But his latest mixing job is for a shake-’em-up scary film — The Invasion, a remake of the 1956 classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Rudloff is one of many audio post-production professionals riding the current wave of horror popularity.

Rudloff says that from a mixer’s perspective, the onscreen action in a horror film is obviously different from a romantic comedy (like Must Love Dogs, which he mixed in 2005), but the overall purpose of the audio is the same no matter the genre: “You are there to support and enhance the storytelling in whatever fashion the filmmaker wishes, but with a horror film you kind of go counter to what you might do in the other genres. A horror film is darker in tone; it’s more ominous, it’s brooding. So in the sound mix, you want to keep your audience uncomfortable.

“We do a lot of things sound-wise to help the filmmaker achieve this, whether it’s misdirecting the audience or building false tensions or scares. We might build a false sense of security before something scary happens,” he says. “Where in other films you might want to have nice, smooth transitions between scenes, in a horror film we might do the opposite: We might make an uneven transition so that it startles the audience a little bit — not spill-the-popcorn startling, but just something that’s a little off and uneven about it. It can be something as subtle as a background sound.”

For instance, he’ll often set up an ambience track that includes a handful of elements, and as he wants the mood to change he’ll take something out. “Hopefully, the audience won’t be aware of it, but it will affect them,” he says. “Sound effects and music are both great tools for doing this, but the key is that you don’t want the audience to feel that you’re [leading] them this way.”

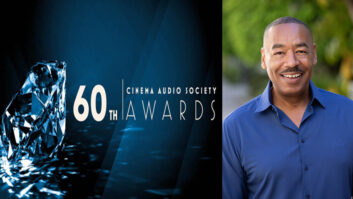

Gregg Rudloff creates “uneasy” sounds for horror films, including most recently for The Invasion.

Melissa Hofmann, who recently completed work on the psychological thriller Captivity after working on such titles as Black Christmas, Thank You for Smoking, My Big Fat Greek Wedding and a slew of thrillers during her varied career, agrees that one difference in the horror genre is that the audience is kept off-balance, often by the lack of sonic build in the soundtrack. “You gotta keep coming at them,” she says. “It’s gotta be, ‘Let’s kill somebody now! Let’s kill somebody else!’ You have to keep the action going.”

In the case of The Invasion, “The movie starts off going great guns,” Rudloff says. “[The viewer] has no idea what’s going on when this movie starts. They are with Nicole Kidman in the middle of her world, which is in utter chaos. So this isn’t a nice, slow-building movie. The moments where Nicole’s world is in total disarray are where the most apparent oddities are and where the weirdness in our sound is. By the same token, the soundscape of this movie is going to change throughout.”

Supervising sound editor Perry Robertson, who has worked on the latest Halloween project, as well as the Rob Zombie flick The Devil’s Rejects and many others, points out that while horror has its own challenges, at times working on a loud movie is easier than a quiet, simple film. “You hear every detail [in a quiet movie], where in some of the bigger scenes [in horror films] it gets so loud that you can hide it if you have bad production [tracks] or whatever. As far as horror goes, we are trying to set moods.”

“If the picture is leading them to be jarred, then we have to support that with sound or lead it with sound,” Hofmann says. “If it’s an environmental sort of thing, then sound can play a huge part of giving a feeling without necessarily the audience even knowing. Those subtle things can help to build up to or support the bigger things. Or on something that’s more psychological, they can be a big element of that subconscious feeling. People don’t even think about it; they just kind of squirm a little and that’s what we are after. I love that — to be able to get to them without them even realizing it, to get them on that visceral level.”

Melissa Hofmann upped the creepy factor in Captivity by manipulating dialog tracks.

Hofmann had the opportunity to do just that while working on Captivity, as she manipulated the character’s dialog tracks to up the film’s creepy factor. “There are two captives in separate rooms who talk through a vent,” she says. “The captor has an intercom between the two rooms, so they can hear each other through the intercom. You can hear some direct sound through glass. Then the captor has a horrible sound torture thing that he plays really loud.”

One of the things that helped make this soundscape work, Hofmann explains, was the fact that the film’s picture editor, Richard Nord, had ideas about the soundscape and temped in an interesting track. “I think that’s one thing that helps a lot,” she says, “if the picture editor is very creative and helps to get an idea of the sound as he goes through.”

It also helped that the sound design team, headed by Scott Sanders and Robertson, had the musical score from Marco Beltrami before their work started. “It was a unique situation, because Marco did a lot of ambient stuff and we had that before we did the sound design, so they were able to integrate the sound,” Hofmann says. “It all worked together to make this rich, thick and compelling soundtrack. There’s a lot of detail.”

Perry Robertson judiciously uses subwoofers to make the audience members jump out of their seat.

“You can’t tell where the design starts and the music ends,” adds Robertson, “or where the music starts and the design ends. It is awesome-sounding.”

Rudloff, Hofmann and Robertson agree that the subwoofer can be used effectively while mixing a horror film. The key, however, is to use that low end judiciously. “Live by the sub, die by the sub,” Hofmann says with a laugh. “The standard is that if you want to make something louder, you make something softer before it. You’ve got to have dynamics.”

“I do a lot of loud movies, but I don’t think that very loud, bombastic sound is the best direction, even for action movies,” Rudloff notes. “I like to use the sub for impact occurrences. Obviously, if there’s an explosion or if somebody kicks in a door, you can use the kick, but I don’t like to have it as a steady element. I think it muddies up the sound; it clouds the details that might be apparent in other areas.”

Sonic details, in fact, seem to be prevalent in horror mixes, Rudloff adds. “I would say that there are more abstract sounds in horror films, things that you wouldn’t normally put in a scene because you’re trying to create this odd world that’s not quite in sync,” he says. “We will use a lot of [sonic] treatment on a horror film. Even on something like a door close, I might add more low end. I may want to have a little weirdness to it. I might add a little flange or pitch it. Again, it’s not a traditional sound that the audience is comfortable with and you can use it on anything, even dialog.”

Then there are the times when you want to make an audience jump. “People go to horror movies because they want to be a little scared,” Robertson says. “I think the problem that people get into is that they pre-sell the hit or the chop with scary music. I think you’ve got to use the element of surprise to make them jump. People are so jaded these days, and it’s hard to make anyone jump anymore. Part of it has to be the picture, part of it has to be the music and part of it is the sound. You hit them with a loud sound using subwoofers. If you get that quick hit from the sub, you’ll feel it in your chest.”

From top to bottom, horror soundscapes are meant to be as fun as the films themselves. Hofmann recalls a time when she was working on a temp mix for the 2003 film Freddy vs. Jason, and director Ronny Yu was in front of the stage jumping up and down. “He would be screaming, ‘Yes, yes! This is the WWE!’ He wasn’t trying to make a cinematic masterpiece,” she says with a laugh. “He wanted it to be a good time. These are two horror kings that are fighting it out, throwing stuff, but doing it in a gory movie fashion. That’s when it’s fun — when you can go for it and they are not taking it too seriously. If you’re doing horror but they are trying to do some masterpiece, then it’s tough to get those two to jibe together.”