MARK SNOW “THE X-FILES” COMPOSER BRINGS CINEMATIC EMOTION TO THE SMALL SCREENThe truth is out there, as The X-Files catchphrase goes. But for X-Files composer Mark Snow, the truth begins at home, where the veteran composer works on each episode’s cinematic score.

“I think honesty is what sounds right or true to you as a composer,” muses Snow, sitting on a director’s chair in his new project studio. The facility is part of his new Mediterranean-style homestead on a quiet residential street in Santa Monica. “Sometimes you can write something that you think they want to hear. Usually that’s the road to disaster, but when you’re truly yourself and you’re happy with what you do, then you can, hopefully, make them happy.”

Being true to himself seems to have worked for the composer. He has been nominated for Emmys nine times, including this year for Music Composition for a Series, and he has won numerous ASCAP Awards, which are scattered in haphazard clumps throughout his studio. The word “honesty” appears more than once in his liner notes to last year’s CD compilation The Snow Files: The Film Music of Mark Snow, which was followed last fall by a CD of his music for Antonio Banderas’ directorial debut, Crazy in Alabama.

On this sunlit February day, Snow was working on show number ten out of the 22 episodes planned for this year’s X-Files, in between working on TV movies such as CBS’s recent In the Name of the People. Post projects include themes for the TV series Millennium and La Femme Nikita and the film Disturbing Behavior.

Snow’s eerie and infectious X-Files theme is perhaps the best example of his philosophy. He got the gig seven years ago after a friend became the producer of the show. He had a few very low-key meetings with The X-Files creator Chris Carter at Snow’s home studio, then located in a pool house in another part of Santa Monica

“The first order of business was I wrote a theme-actually I wrote four themes,” Snow recalls. “Chris sent me tons of CDs and said, ‘I liked the drums here, I like the vocals here, I like the strings here, I like the piano on this one.’ You know, ack! It was everything: The Smiths, alternative rock ‘n’ roll to Philip Glass to Stravinsky to jazz-totally eclectic.

“So we went through four themes, and [Carter] was very polite and respectful and said, ‘Well, that’s really great, but it’s just…,’ and so after the fourth one, I said, ‘Listen, why don’t I try one on my own, and I’ll call you when it’s ready.’ He said, ‘That’s fine.’ So I put my hand down on the keyboard, and I had some delay echo, a repeated ‘dadada dadada dadada dadada,’ and so I thought, ‘Oooh, that would be a cool accompaniment. Put a bed of sustain on it and came up with this whistle thing.”

The whistle emanates from “Whistling Joe” on his E-mu Proteus 2 MIDI unit. “Everything was laid out except what I was going to play the melody with, so I tried everything-pianos, woodwinds, squeeching things and vocals-and came across this whistle,” Snow explains. “I thought, ‘Boy, that’s interesting. It’s eerie and sort of unexpected.’ Then [Carter] came back and heard it and thought it was really great. It was a little more overproduced than it is now-bells and some voices-and he said, ‘Just take that stuff out.’ Just the three basic elements here: melody, accompaniment and the low bass supporting sustains.”

Snow thought it was good, but he didn’t think it was going to be a hit from one of the most popular and influential shows of the ’90s. Still, The X-Files turned into the composer’s biggest break since grabbing his first job. He grew up in Brooklyn, and after playing oboe with the encouragement of his drummer father and kindergarten teacher mother, Snow attended New York City’s High School of Music and Art and, eventually, Juilliard, where he roomed with fellow composer Michael Kamen. (Together, they started the New York Rock ‘n’ Roll Ensemble, which mixed classical and pop music.) After producing records for a brief time, Snow decided to move to Los Angeles with his wife, Glynn, whose sister is actress Tyne Daley. Daley’s husband was then acting in the TV series The Rookies, and after landing a meeting with producer Aaron Spelling, Snow got his first gig.

He went on to score such TV shows as Hart to Hart and Falcon Crest, as well as TV movies such as Something About Amelia, The Boy in the Plastic Bubble and The Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, one of the pieces that pleases Snow most.

Now Snow begins work every morning at 6 or 7 and continues until 3 or 4. Each X-Files score takes about five to six days, although he’s had to crank some out in three. He starts with a script, but the ideas don’t start to ignite until he gets a locked picture. “The hardest part of each score is always the beginning, in which you get your sort of palette of sound going and your themes,” he explains. “Once that first piece is written for the show, all the other pieces seem to sort of fall into place. There are anywhere from eight- to ten-minute pieces or cues in a show, and I’ll try to do those first and then be able to take the themes or the sounds from that one big piece and incorporate it into the shorter pieces.”

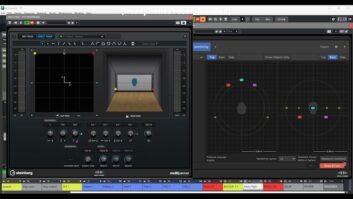

The fact that he composes, plays and records each episode’s music entirely on his home studio’s 32-voice Synclavier makes it easier to create the series’ rich and complex scores. “It’s a phenomenal storage retrieval and recording device,” he says, adding that he only put together a home setup a few years before the start of The X-Files. “The instruments it does especially well are all percussion, all keyboards, harps, the strings…and the woodwinds are pretty good. The brass is good, but mostly anything that is plucked or hit is particularly wonderful, and you would never know it’s not real. It’s so elegant in terms of speed and quickness-I don’t need five or six other keyboards.”

Snow also relies on the E-mu Proteus MIDI modules, which contain everything from pop instruments to world music sounds. A Korg SR Wavestation was also a mainstay in the first few years of The X-Files. “It had a lot of great ambient, sustain, sound design-style things,” he says.

“In the beginning of X-Files, they wanted a very simple, minimal, sustain kind of sound, and it’s funny because I remember working for someone before X-Files and a director saying, ‘You give me any synthesizer sounds-you’re fired.’ Then the X-Files guys come along and say, ‘If you do anything like the traditional stuff, you’re done,'” he adds with a chuckle. Other gear includes a Roland R8M drum percussion module-which has “some great, good-old drum sounds,” he says-four Roland S-760 samplers, a JVC BR-2U66BR2 professional S-VHS deck, and Yamaha NS-10 reference monitors.

He mixes and monitors through a new Mackie Digital 8-bus, which replaced his Soundcraft Sapphyre. The Mackie has impressed Snow with its compact size and low price. “You can save mixes, which saves the actual panning of each track to left, right or center, the relative volume relationship and the EQ and all the effects, delay and echo. So you can be in one show where it’s lush strings and soft and swimming all over the place, and then call up another one and it’s a hard-driving, real dry, percussive mix,” he says. “It’s especially great if you’re working on two or three shows at once and they’re totally different styles and setups and sounds. So this is really quite powerful.” He’s also holding onto some of his old reverb and EQ units: a PCM 70, Lexicon LXP-1, Alesis QuadraVerb, and a Summit EQ and compressor owned by his mix engineer, Larold Rebhun.

Rebhun, who has worked with Snow for years-as have music editors Jeff Charbonneau and Marty Wereski-says, “Occasionally I’ll throw in some little 3-D effect, but the post-production people don’t like that. They like to expand beyond the speakers themselves, and they mix it in Dolby Surround. I think they do add a little bit of reverb occasionally, but mostly for Mark, I just make everything sound good. I work with several other composers, and Mark’s music just seems to fall together, and it’s very easy for me to mix.”

The scores for The X-Files, which involve as much as 35 minutes of music for the 45 minutes on air, have evolved from very minimal pieces with few notes and lots of short cues. “I’d listen to some of the shows, and I’d think, ‘Oh, man, this is just too bland. We need something more,'” Snow remembers. “So as the years went by, the music became more musical, in combination with all the electronic sound effects. So there would be a melodic thing or a traditional thing, but then all of a sudden, in contrast to that, there would be some really cool ambient percussion with electronic sustain elements, and you know, the combination of the two is what it has evolved into.”

Snow admits he has a few signature sounds: “The relationships of major seconds that are spaced in a very atonal way. Tri-tones are a big favorite of mine, and it sort of got into scores influenced by Mahler or late Beethoven. Thicker, brooding, dark composers that weren’t quite too modern yet. Some of the real romantics but the dark side of that-Mahler with electronic stuff.”

The range of shows on The X-Files gives Snow a chance to stretch creatively and incorporate some of his favorite influences. “If it’s a very serious show, something about Mulder’s sister or his mother, something like that, then I know it has to be a certain kind of sound I’ve done before on these shows,” he explains. “But if it’s a monster-of-the-week, then it’s wide open.”

His score for the X-Files feature film allowed Snow to combine a large orchestra with his electronics. “I would do the electronic part first and lay down tracks on this DA-88 tape, which you could add 20, 40 other tracks of music onto. So there was a quick track, which kept the orchestra in sync with the electronic stuff. We played the tape, and the orchestra heard that, and I knew where to cue them in,” he says, adding he doesn’t use a notation program and instead depends on orchestrators Lolita Ritmanis and Debbie Lurie.

Although Snow was able to explore everything from Dixieland to traditional orchestration in his work for Crazy in Alabama, he still longs to do a film like American Beauty, “the type of movie which is sort of small and very sophisticated-and for a composer, it’s really, really wide open as to the choices that you make,” he says. “If you do a big action-adventure movie, it just has to be fast and loud.

“I think one’s emotional response to a show, whether it’s a movie or a TV show, is the most critical thing. It’s important to be technically a good musician or technically a good composer, but some composers’ music that I really love and respect doesn’t really seem to be based seriously on technical things but emotional things, things that give it a personality and sound that’s special,” he explains. “For example, Ennio Morricone’s technique is not quite up to that of John Williams’ but there’s an emotional quality that just, oh, is just so powerful. Sometimes the most simple things can have such poignancy to them.”