When it comes to audio processing, we’re in a golden age. We have plug-ins available that can get inside of polyphonic audio and edit individual notes, and even edit the transient and tonal parts of audio separately. Correcting rhythmic inaccuracies has gotten easier, and pitch-correction algorithms have become more powerful and transparent. Pitch-shifting is so accurate that it’s possible to re-harmonize recorded tracks seamlessly, as long as the intervals aren’t too large. Time-stretching algorithms allow you to speed up or slow down audio by a couple of BPM without creating artifacts, making it possible to adjust an entire song’s tempo if necessary—after the fact.

What’s more, modeling of analog hardware processors has gotten appreciably better. So much so that many engineers and producers who have a choice of the original hardware or the modeled plug-in will sometimes choose the latter—something that would have been unheard of ten years ago.

With all that processing power at your fingertips, it’s hard for it not to impact the way you work—both in helpful and not-so-helpful ways. Let’s start with the former. Whereas in the past you might have asked a vocalist to re-sing any lines or words with pitch inaccuracies in them, now you can focus more on performance, and fix the pitch later. That’s a welcome change, as you no longer have to worry about a singer getting so freaked out over pitch issues that it impacts his or her ability to relax and nail the emotion.

And even though I’m hesitant to mess with another musician’s groove (less so when it’s a part I played), I will occasionally use the audio quantizing features in my DAW to fix a measure or two of an instrumental part that needs time correction.

I’ve also gotten accustomed to using the cut/copy/paste editing in my DAW to fix problems within a track. I’ll replace a badly struck note with one from another part of the song, move individual notes around in time to make them line up better with those on other tracks, and so forth. That’s not signal processing, per se, but it’s still using digital features for correction.

What concerns me a little is how having all this potent power to correct has changed my mindset to where my first impulse for almost any problem is to think that I’ll fix it in the mix with plug-ins or my DAW’s editing features. Although it mostly works out fine, thanks to the power of the software, there are times when I find myself unnecessarily in the digital weeds, when I could have solved the issue more organically.

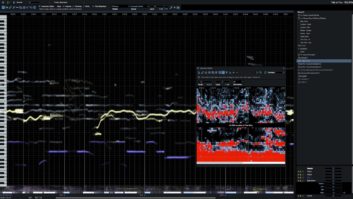

I’ll give you an example: I was producing an instrumental piece recently and noticed that the mandolin track I’d played and recorded had some out-of-tune notes inside some of the chords. The first place my mind went was to a digital remedy. “I can fix those individual notes in Melodyne using its polyphonic mode—no problem!” So, I spent about 20 minutes or so messing around with it, and I was able to improve it considerably. But then it hit me: it would have been a lot faster and easier just to re-record the part. I could have done it in under five minutes, and I probably would have gotten an even better result.

This is all to say that although we have awesome processing available to us, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that sometimes it’s easier and better to fix mistakes the old-fashioned way, by punching in or re-recording.