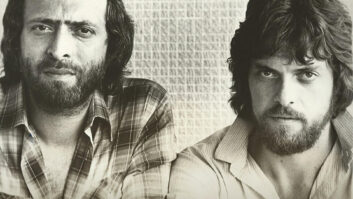

An ochre harvest moon rises over the eastern rim of New Orleans. It rotates smoothly across the black sky, and just before it sinks below the horizon, the door of a nondescript building (a converted mortuary, actually) creaks open. Soft light from inside briefly illuminates two night creatures, who exit and go their separate ways, eager to reach shelter before the morning sun burns their pale skin. That was how I first pictured Trent Reznor and Alan Moulder, at work at Reznor’s Nothing Studios. Okay, it’s a bit heavy on the Anne Rice, but listen to Nine Inch Nails’ latest release a few times and see if your thoughts don’t drift toward the dark side. The sound is elegant, wicked and occasionally bloodcurdling-by turns both open and claustrophobic. A line from Rolling Stone’s review puts its controlled insanity into perspective: “In a pop year silly with baby talk and plastic mambo, the thundering overindulgence of The Fragile is not a trial, it’s a f-king relief!”

Yes. Well, co-producer, recordist and mixer Alan Moulder is no stranger to this kind of creativity. In addition to The Fragile, his lengthy discography boasts numerous other credits best described as “intense.” He was co-producer and mixer on the Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness and mixer on their Siamese Dream. He also mixed NIN’s The Downward Spiral. Delve a bit further and you’ll find Moulder was behind the desk for works by singular artists such as the Jesus and Mary Chain, Moby, My Bloody Valentine, Marilyn Manson, Erasure, u2, Shakespear’s Sister, Curve and, neither last nor least, Tom Jones.

Just off a two-year stint at the New Orleans studio where The Fragile was constructed, and hoping for some holiday time in his English homeland, the affable and rather soft-spoken Moulder instead found himself hard at work. Mix nabbed him for this phone interview during a week when he was mixing projects for both NIN and the Pumpkins. (Like I said, intense!) We got our conversation started when he took a short break from sorting takes at London’s Rak Studios while Trent and the boys were off shooting footage for a video.

How did you get started in recording?

I started off playing guitar. I’m from a small town in Lincolnshire, where I was in a band and very interested in music. After I was done with school I managed to get a job at Trident Studios in London as a runner-a tea boy as we call them. But I left after a month; I hadn’t quite finished being in bands, and I realized that if I was working in the studio I’d have no time for it. Instead, I went to work in the Ministry of Agriculture, doing research into plant diseases. It was a job that gave me the freedom to play in bands at night and on weekends.

After four years of that I thought, “You’re not going to make it, and being in the studio is more fun anyway!” Meanwhile, the guy who used to be head engineer at Trident had bought the studio, so I rang him up. I got lucky and walked into an assistant’s job without having to go back to being a tea boy. Which was a bit difficult, actually, because I jumped over three tea boys who’d been there six months; I wasn’t very popular in the beginning. Fortunately, two of them got fired very quickly and the other got promoted, so after a month all was sweet. But I was starting quite late, you see. I was 24.

God, yes, so old. Well, at least you had that training as a musician.

That’s true; it was very good learning. It gave me the musical point of view, and it also gave me the knowledge that I’d done that route, and was making a decision to put it away and go for another career. I could put 100 percent into engineering, which you need to do; you have to be committed or you won’t get on.

Was Trident still all Trident consoles at that time?

When I first arrived there were three rooms. Two of them had old Trident consoles, and one room had an SSL. So, yes, we used the old A Range Trident board, which was great, but I ended up spending a lot of time in the SSL room, which was mainly for mixing.

Trident was a fantastic studio for training; we had an incredible staff when I was there. There was Flood, who I used to assist a fair bit; we had Mark “Spike” Stent, Paul Corkett and Steve Osborne. A lot of people would use the house engineers, and part of the job of the house engineer was to train the assistants. Also, Trident pushed you into engineering very quickly. It was a baptism of fire; they’d toss you off the deep end, and you sank or swam.

That concept of having staff engineers is almost extinct these days.

Yes, that’s a big demise, I think, a real shame. I was very lucky [at Trident] because they gave you so much freedom, and you were encouraged. It was very tough, of course; if you did mess up you were out. But at least you were given the chance.

What kind of music were you working on?

A cross section. There was a company called Record Shack that did high-energy disco that we all used to end up cutting our teeth on. It was mainly drum machines and DI stuff; you didn’t need fantastic technical expertise to record it. And they worked very quickly, so it made you get your speed together.

And then, because it wasn’t a particularly high-tech studio, and it was cheap, we used to get a lot of alternative bands. They could get the studio at a reasonable price, and they’d get the house engineer included. I remember Flood doing Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds, stuff like that. I stayed there about four years, then the studio changed hands, and I went freelance.

Once you went freelance, how did you get work?

I’d met Dave Stewart of Eurythmics because my wife, Toni Halliday, is in a band called Curve that’s signed to his record label; I started doing work with Dave and some of his other bands. He signed me to his management company, where I worked with Karen Ciccone, who is still my manager now, and I had a few clients from Trident. Actually, I was doing a lot of dance stuff at this time, and it looked like I was going to be a dance mixer.

I also knew Alan McGee from Creation Records. Alan managed the Jesus and Mary Chain-that’s how I’d got to work with them. They asked me to do Automatic, and when Alan heard it, he asked me to do some of his other bands like Ride and My Bloody Valentine. So I took a bit of a change into the kind of music I was actually into and then went on that way.

Still, the dance music wasn’t bad training.

No, I enjoyed doing it. It was when they were beginning to construct tracks up from just solo vocals; you were re-creating everything, and in a way, it was kind of punk rock-you could throw everything at it. It was great fun, and it helped me get my low end together.

How did it help with your low end?

Club stuff has to have heavy bottom end, and you have to get it tight and punchy. I grew to really like that. When I went to work with rock bands, I tried to incorporate that kind of low end, which is probably a more American-type sound-rock with a big, thick bottom. It’s just having the bass and bass drum loud, and getting them to sit without compressing them too much, which takes the low end out. Also, normally with SSLs, I put a Focusrite EQ across the mix and add a bit of low end as well as a bit of high; the Focusrite seems to work really well with the SSL board.

Meanwhile, you also had an affinity for guitars.

That helped I guess, doing bands like the Mary Chain. I loved working with them-their sound was so irreverent and abnormal.

Yes, you seem to have an affinity for that as well.

[Laughs] One thing has led to another. I’ve been fortunate, I must admit, in the bands that have picked to work with me. You’re only as good as the bands you’ve been working with.

Trent Reznor’s studio really is a converted mortuary, right? What’s it like?

Amazing. He has two rooms-the main room is an SSL G-Plus with ultimation. The main thing is, it sounds good-no surprises when you leave. It was designed by Coco, and despite the fact that it’s a large control room, the big monitors are really good. The mains are Tannoys built into the wall. Then, Trent decided that he wanted to get some of that “jeep going past” kind of thing, so he’s got 18-inch JBL subwoofers and a 2K amp just to drive them. When you turn the subs on, your back starts shaking; it’s great.

Equipment-wise, you’ve got every piece of gear you could want, and there’s two of nearly everything. Also, everything is very accessible. Brian Pollack, who looks after the studio, is an engineer, so it’s set up the way you like to work.

In general, you stick to SSL consoles.

I like the way they work. I know some people are funny about the sound, but I think it’s good. I’m not tied to SSL; I’ll work on Neves or pretty much anything. I think all desks have their good and bad points, so it’s best to focus on their good points, and there are plenty of good ones on SSLs. I know some people think they’re not as open, or as deep, or whatever. I’ve never had a problem with them.

Do you like them for both recording and mixing?

It depends. If I was doing a live band it wouldn’t be my console of choice. I find that old Neve recording with SSL mixing is a happy marriage. Although I haven’t used the J Series yet; that might change my mind.

Really, I use whatever; I think that’s more of an English thing as well, by the way. We don’t tend to have the finances or resources to be quite so fussy; you have to go with what you’ve got. I used to work a lot on indie bands who didn’t have large budgets; I’ve been stuck with a band in a tiny studio with a desk I can’t even remember, and all I had was SM57s. You have to make a record with that; you can’t start complaining because you haven’t got the right Neve modules.

I think a lot of American engineers are lucky enough to be spoiled in that way, whereas we’ve had to rough it a bit. You’re given a budget that’s low, and you have to get on with it and make the best of it.

Can you describe the process of making The Fragile?

The process changed, as you can imagine. Trent had some demos and a list of atmospheric territories he wanted to attack in different ways-electronic, or more organic and funky. So, we just started experimenting. When we’d gone through the demos, we started doing new stuff, which would involve, sometimes, just making sounds. We set Trent up in a room with a whole pile of junk, really, and four mics, and he’d just hit things and we’d record it. Sometimes we’d play a loop of something and he’d play along on different boxes, or big plastic water bottles, or shakers-he’d pick up whatever appealed to him. We spent a long time cutting that together, and we made quite a few songs out of it. Sometimes it was based on him playing to the loop, and sometimes, it was just based on the samples.

Then we’d build on it-put some basses on and guitars-and then we’d move on. We never got stuck on anything for too long; we just kept moving. What was good about that was, when you’d come back, after not listening to it for a month, it was a pleasant surprise, much better than we thought. We were having a lot of fun creating stuff, and we kept doing more and more. The down side was we ended up with something like 117 tracks. I knew definitely then that we were into it for the long haul.

One hundred seventeen tracks.

Yes. The strong ones survived. We just kept going round, improving, and then we’d have big review sessions where we would go through everything and say, “No, that one’s out.” Sometimes we’d get bored and have lab days, making percussion banks or putting drum kits in different rooms and running them though P.A.s. A new piece of gear would arrive, and we’d spend half a day exploring it-you know how it is, when you get a new toy you always get fantastic things out of it in the beginning.

Well, you ended up with a lot going on for the vocals to cut through. How did you record them?

In the end, it got down to two main chains: the 58 for the more loudly sung, cutting vocals, into a Neve 1066, then into a Distressor. Everything went straight into Pro Tools, and it wasn’t 24-bit. Twenty-four bit came out when we were in the middle and we thought, “We’re committed, we’re not going back, forget it!” We did go through an Apogee, the stereo one; some of it was self-limited, and some of it wasn’t.

For the other chain, for the more breathy, high-sounding vocals, Trent has one of the new AKG C-12 valve mics, and we also used the Sony, the one with the big hair-dryer heat sink, into an Avalon VT737P. Sometimes we’d use an 1176, but those were the main chains. Trent always sings in the control room; we just turn the speakers down and put headphones on. It’s the quickest, much easier for communication.

You’ve got piles of guitars to deal with. I suppose stereo placement is one of your tools to make them all work.

Yes. Rather than just going for “down the middle” or “hard left or right” or “9 o’clock,” you can find little bits; just by wiggling them around a bit you’ll give them a different space.

This is really dull to say but, generally, on guitars in the mix, I do absolutely nothing. A little bit of EQ to separate if there’s a whole wodge of them and a very slight board compression. I use the channel compressor on the SSL set so it’s hardly working. That gives it a bit of warmth or fatness.

I do use filters a lot, probably more than EQ. On guitars, I sometimes find that if you put the highpass filter in slightly, it can clear out a lot; also, sometimes I filter the top off.

I know you used all sorts of different guitar setups on The Fragile, but isn’t there something basic you’d start with?

I don’t have a particular setup. With other bands, it’s what the guitarist likes to use; then if we’re struggling, I’ll suggest something. In this case, Trent had a few preamps; in particular, we used the DigiTech 2112 a lot. It’s stereo, and you can route a tube preamp to one side and a solid-state one to the other. We’d do that, then send them to a Boogie power amp and out to a pair of Boogie 4-by-12s. It sounds really wide with different preamps on each side.

Distortion is one of the main artistic linchpins of the record. What are some of the things you used to get it?

We’d go on pedal-buying trips a lot. Swollen Pickle was very popular, by Way Huge. They don’t make them anymore. We used Lovetime, Big Cheese, Fox, The Tone Machine, and some things were done on the Eventide DSP 4000.

There’s a pedal called the Fuzz Factory we liked, and we used the Shinai fuzz/wah which the Jesus and Mary Chain used to get their thin, wiry distortions. There’s the Roger Mayer Voodoo Axe, the Danelectro Daddy-O…I could keep going on. Also, often they were strung together.

With so much going on, and so many different kinds of distortion, how do you carve out niches for each part?

I suppose some of it’s done by taste and fine-tuning while you’re recording. You get a sound that works with what else is there. The way Trent works, you’re always trying something different. He’d want to do a guitar overdub, without particularly having a part in mind, so we’d grab a load of pedals and plug them together-either plug the pedal chain into a valve DI, or sometimes we’d put it into an amp through speakers or sometimes through an amp into a speaker simulator. He’d get a sound and go, “Well, that’s quite interesting,” and he’d come up with a part based around the sound, which is quite a liberating way to do guitars.

That’s opposite to how a lot of people work.

It is. On this album there was no real agenda or plan; it all kind of unfurled as we went along. In hindsight, when I listened back to it, it seemed that we knew what we were doing, but we didn’t. We just didn’t want to pull out the old tricks. For a lot of the sounds that Trent had gotten in the past, particularly on Downward Spiral, people seem to have created plug-ins that do them immediately. So, he couldn’t use those; he had to move on.

It really was a different way of making a record. We both said we were glad we did it, and that we enjoyed it, but we wouldn’t do it again. Both of us were, I think, at the point that we wanted to have that indulgence. Especially as an engineer, it’s a dream to be able to indulge yourself in sound as much as we did.

What did you mix to?

DAT, 16-bit. Through the Apogees. In hindsight, I would have liked to have gone to half-inch, but since I thought we would be doing more post-production, going digital back to Pro Tools, I thought we should go to DAT.

Do you think you have a special talent for working with people with strong personalities?

My preference is working with people with strong personalities. They know what they’re doing; they’re not looking for you to give them a sound. You work together, which I like; I always work as a co-producer. I believe in working with bands that inspire me; it would be a complete con to take solo production on any of these bands’ records because they have such massive input. You’re there as devil’s advocate, somebody to push them, as a sounding board, or to give them ideas. A lot of the time, you’re there to filter through their ideas. A lot of the people I work with are not short of ideas or parts-they’ve got too many! They just want somebody to go “that one!”

To help sort it out.

Yeah. So, if somebody says, “The guy in the band’s a control freak,” I think, “Fantastic.” Because, for me, they’re much easier people to work with.

Is there a piece of equipment you can’t do without?

I’ve got a Forat F16 that I use to trigger kicks and snares. Most people don’t admit doing this, but I’m going to put my hand up and go, “I do.” I don’t use them to replace; I use them to put behind, because I don’t really like reverbs on drums. Instead I’ll put a low, whoompy-sounding kick beneath the kick drum to give it sub. Sometimes you can’t EQ that in, or if you EQ it in, it gets muddy. I find it works with a blend, with the recorded kick drum as the main sound, the low one underneath, and then you just sneak in the subharmonic dbx on that.

The dbx boom box?

Yes. You don’t have a lot of bleed going on and you can get a very present kick drum. So I’ll have a whoompy one or sometimes a clicky one just to give it a bit of definition, and just behind the snare I’ll put an ambient snare sample instead of using a reverb. A lot of people are a bit Luddite about samples, but I don’t see the difference between putting an ambient snare sample behind the snare and using reverb. Some people reach for the same reverb to put on the snare all the time-they think that’s fine and a sample isn’t. I don’t see the difference, apart from the fact that, to me, the snare sample sounds more natural than the digital reverb.

You use the Forat because you have sounds in it you’ve collected over the years.

I use it because it’s quick. I have got a lot of samples in it that I can quickly flick through and see which ones suit the track. I don’t like replacing sounds using MIDI maps because I find they drift. Especially with kick drums, the attack’s not the same. The next thing, I suppose, would be to record it into digital audio and move it so it’s spot-on, but at this stage I find the Forat much quicker. Also I can change the tuning, adjusting it as I go. I got into it early on, working with the indie bands who would get me in to mix records that had been recorded incredibly quickly in very small studios. The drum sounds weren’t as good as they could have been, and they always wanted the guitars deafeningly loud. The only way to get the drums to cut, without having them loud, was to have a sample going underneath to give it some kind of presence and definition. The Forat’s done me well; I think there are only two in England now, and every time I reach to turn it on I hope and pray that it’s still working.

It’s a bit surprising, but I like listening to The Fragile at low volume.

Yes, I definitely try to make a mix sound good quiet as well so I tend to mix very quietly. I have it loud at the beginning to get the general vibe, the feel of the rhythm and the drums, but once I’m happy with the basic way it’s sitting, most of the balancing is done on the Auratone.

A single Auratone.

Yes. Also, the Auratone makes me mix the guitars louder.

What other monitors do you like?

KRK 7000s. Butch Vig and Billy [Corgan] were using them on Siamese Dream, and I got into them. Before that I was using NS-10s as everybody was. I grew to really like the KRKs. They have, since I’ve got them, time-aligned the bottom end, and what on earth possessed them to do that I can’t imagine. I know at least five people who are queuing up for the old ones and don’t want the new ones. Of all their range of speakers, and they’ve got loads of them, to me these are by far the most accurate. They’re not particularly flattering, but for balance, I find them great. Everybody I work with likes them and wants a pair, and they can’t get them because they don’t make them.

Any new gear you’re impressed with?

It’s an amazing time, I think-there’s so much great gear that’s come out. Trent got one of those Virus keyboards, which was fantastic, and there’s a sampling box-I think it’s the SP-808 Roland-which has inboard effects which we used a lot. There’s Distressors, and the TC FireworX is good. I’ve also got a dbx 160S, which I really like. I can’t remember a time when so much good gear was coming out-it’s expensive trying to keep up.

Do you find yourself doing less in the mix than you used to?

Yes, I’m not that keen to reach for the EQ or the compressor. I think that’s something you learn, to try to make what’s there work best on its own. I’ve learned that from the artists I’ve worked with, who are precious about their sound. They’ve spent a long while getting the guitar sound, and you’re just coming to mix; they don’t want you to steam in and ruin it. So, panning, sometimes a bit of slight compression-I guess that’s dull really, isn’t it?

Trent Reznor has said that the random button on a CD player is his enemy; obviously, the sequence on The Fragile was very important. It’s interesting that you brought in an outside person, namely Bob Ezrin, [Pink Floyd, Lou Reed] to help sequence the album.

We were just punch-drunk really. I tried sequencing, and it took me three hours to get the first four. We thought we hadn’t any objectivity left and it would be great to get somebody else to help. The running order was crucial; we knew if it was wrong it would be a very arduous journey.

It’s definitely an album, one of the few these days, that sounds better when you listen to it all the way through. A lot of time was spent getting that right.

Making a whole album is a lot of work in itself. You’ve done two doubles, Mellon Collie and The Fragile. Any hints on keeping up the stamina to get through them?

[Laughs] I don’t like double albums. But I go back again to my training-working at Trident was almost like being at boot camp. From the beginning, you were thrown into the long-hour deep end of sleep deprivation and of being able to keep it together. Stamina-wise, I can only think it’s enthusiasm that keeps you going. On both of those albums, I was working with fantastic bands- you couldn’t ask for more inspiration than you got from them. Every day you wake up and it’s not a drudge to go into work; you’re lucky to be there. It’s really just enjoying it and loving it.

PRODUCERThe Clean: Vehicle (Rough Trade, 1990)

The Sundays: Reading, Writing &Arithmetic (Geffen, 1990)

Shakespear’s Sister: Hormonally Yours(London/PolyGram, 1991) (also engineer)

Adorable: Against Perfection (EMI, 1993)

Swervedriver: Mezcal Head (A&M/Creation, 1993) (also engineer and mixengineer) and 99th Dream (Zero Hour, 1998) (also mix engineer)

Tom Jones: Lead & How to Swing It(Interscope, 1994)

Smashing Pumpkins: Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness (Virgin, 1995) andThirty Three (Virgin, 1996) (also mix engineer)

Remy Zero: Villa Elaine (Geffen, 1998) (also mix engineer)

Nine Inch Nails: The Fragile (Nothing/Interscope, 1999) (also engineer and mix engineer)

ENGINEEREurythmics: Savage (Sire, 1987)

Erasure: Crackers International (Sire, 1988)

Depeche Mode: 101 (Sire/Warner Bros., 1989)

The Jesus and Mary Chain: Automatic(Warner Bros., 1989) (also mix engineer) and Honey’s Dead (Warner Bros., 1992) (also mix engineer)

My Bloody Valentine: Glider (Sire, 1989) and Loveless (Sire/WEA, 1991)

Curve: Cuckoo (Virgin, 1993)

Marilyn Manson: Portrait of an American Family (Nothing/Interscope, 1994) (also assistant producer and mix engineer)

Echobelly: Everybody’s Got One(Epic/Fauve/Rhythm King, 1994)

Various Artists: S.F.W. soundtrack (A&M, 1995) (also mix engineer)

Various Artists: Ocean of Sound(Ambient, 1996)

U2: Pop (Island/PolyGram, 1997)

MIX ENGINEERRide: Nowhere (Sire, 1990) andSmile (Sire, 1990) (remix engineer andengineer)

The Boo Radleys: Giant Steps (Sony, 1993) (remix engineer)

Lush: Split (4AD, 1994)

Nine Inch Nails: The Downward Spiral(Nothing/TVT/Interscope, 1994)

Elastica: Elastica (Geffen, 1995)

Monster Magnet: I Talk to Planets (A&M, 1995)

The Cure: Wild Mood Swings (Elektra/Asylum, 1996)

Laibach: Jesus Christ Superstars (Mute, 1996)

Blur: M.O.R. (Food, 1997)

Various Artists: Lost Highwaysoundtrack (Nothing/Interscope, 1997)

Moby: Animal Rights (Elektra, 1996) (also engineer) and I Like to Score (Elektra/Asylum, 1997)

David Arnold: Tomorrow Never Diessoundtrack (A&M, 1997)

Depeche Mode: The Singles 86>98(Reprise/Warner Bros., 1998) (remix engineer)

Various Artists: Never Been Kissedsoundtrack (Capitol, 1999)