Engineers are often involved in the pre-production of records, sometimes sitting in on rehearsals with the producer and the band. In the case of “A Taste of Honey,” engineer Larry Levine was actually bold enough to suggest the song to the producer/artist Herb Alpert.

“We were in the mastering room at Gold Star Recording Studios [L.A.], and I was making him an acetate copy of another song he was going to record, a song called ‘Whipped Cream,’” Levine recalls. “He told me that that was the name of his next record, and that it was going to be all about food. So, I suggested ‘A Taste of Honey.’ That’s how it got onto Herb’s list.” (Other song titles on the album included “Tangerine,” “Green Peppers,” “Peanuts,” “Lollipops and Roses” and “El Garbanzo.”)

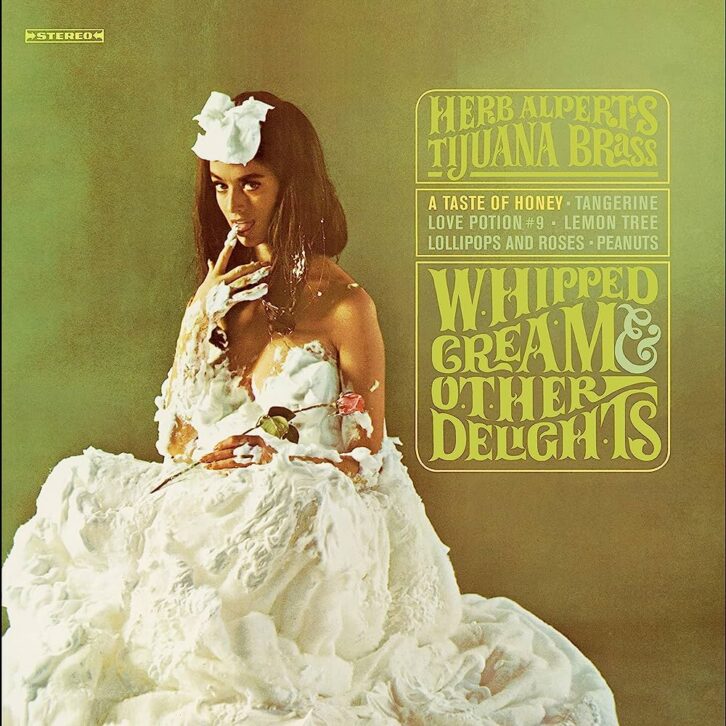

The album, Whipped Cream & Other Delights, reached Number One on the pop charts after its release in April 1965, and spawned several hit singles, the biggest of which was “A Taste of Honey,” which also copped Grammy Awards that year for Record of the Year, Best Pop Arrangement and Best Engineered Recording — Non-classical. Not bad for an instrumental.

Alpert was already a successful music industry veteran by the time he hit it big with “A Taste of Honey.” In the late ’50s, working with manager/promoter Lou Adler, he had helped in the careers of both Sam Cooke and Jan & Dean. He parlayed his triumphs in that area to the founding of A&M Records in ’62 with his partner, producer Jerry Moss. A trumpeter since the ’40s, Alpert was inspired to start the Tijuana Brass in L.A. after seeing a bullfight in Mexico and digging the local music there.

In his own garage studio, he experimented with overdubbing his trumpet parts, and that technique became the basis of some of his earliest Tijuana Brass compositions, including “The Lonely Bull,” which became the centerpiece of the group’s first album, which was also the first release on A&M Records. With its eclectic combo of Latin, jazz and easy listening sounds, the Tijuana Brass managed to appeal to a broad cross-section of adults and a good number of young people in the era just before The Beatles hit it big in America. And they would prove to have longevity that most instrumental hitmakers of the early ’60s did not; they continued to thrive during the British Invasion.

The Scott/Marlow tune “A Taste of Honey” had been recorded by The Beatles on their debut album, Please, Please Me, in 1963. Levine joined Alpert and Moss, who were co-producing the Tijuana Brass records, in late 1964 to cut the track in Studio A at Gold Star, where Levine was a staff engineer. Alpert had done some of his previous records, including the hit “The Lonely Bull” (1962) at United/Western Studios in Hollywood. However, Levine says, Alpert wanted a bigger, brighter sound, and came to Gold Star and Levine because of what he had heard of Phil Spector’s records, many of which Levine had engineered in Studio A. “I knew ‘Lonely Bull,’ and the whole Tijuana Brass sound was a real departure, so I was happy about the prospect of working with them,” says Levine. “And I was also thrilled to be working with Herb and Jerry, who everyone said were two great guys to work with.”

The basic track for “A Taste of Honey” was developed by Alpert in the studio with many of L.A.’s top studio session players, including Wrecking Crew drummer Hal Blaine. The drums were in the center of the relatively small (19×24-foot) Studio A, with the rest of the musicians clustered around them; the rest of the instrumentation included a Fender bass, an electric and an acoustic guitar, a piano and percussion played by Julius Wechter. Alpert liked to direct the basic tracks and overdub his trumpet parts later, along with the rest of the horn section. The drums were miked with a Neumann 67 above and an RCA 77 in the kick drum. The electric guitar amp had a Shure 57 pointed straight at the speaker about six inches away. Levine miked the acoustic guitar with an E-V RE-15, running all of them to a Scully 4-track deck through Studio A’s custom-made 12-input console.

Classic Tracks: Chicago’s “25 or 6 to 4”

The arrangement was a tricky one: It began with a legato Mariachi-esque pair of trumpets drawling the chorus melody. (Alpert’s frequent use of Mexican-influenced horn parts on songs like “The Lonely Bull,” “Spanish Flea” and “Tijuana Taxi” led his sound to be dubbed “Ameriachi.”) The track then quickly made the transition to a walking four-on-the-floor beat, with the musicians landing on the one beat together after a tacit, a pattern that repeats three times in the song.

Or so it read on the chart. The reality was, L.A.’s finest had a great deal of difficulty landing on the beat together that day. “They tried four or five times after we started tape rolling to all get in back on the beat,” recalls Levine. “And these were the best session players in Hollywood. It was more funny than it was frustrating, even for Herb. Strangely, it was almost like a relief to know that sometimes even these guys couldn’t get it. When we went back to the old tapes a few months ago in preparation for a new record, you could hear the musicians having this discussion on the outtakes as to why the heck they couldn’t come in on the beat together. It was actually pretty funny. It was just one of those things. Had it been another day, it would have gone down fine.”

The solution was found when Levine and Alpert decided that they would record the basic track in sections, and Levine would edit them together with the right amount of tape between edits to match the tempo. To provide him with a cue for the edits, Alpert asked Blaine to count it off, and Blaine responded by using his kick drum to pound out eight quarter notes before each up-tempo section. Later, when Levine was editing the track, Alpert began to show a fondness for the kick drum out in the track stark naked like that, and ultimately decided to keep it in instead of leaving the space blank, as he originally had conceived it. And that turned out to give “A Taste of Honey” one more killer hook. The kick drum was used just as Levine had recorded it, when it was supposed to be used solely as an edit cue. That it sounded as good as it did, Levine credits to Blaine’s playing: “There are some musicians who, for one reason or another, just seem to own their instrument. They don’t have to think about what they’re playing — the instrument is just an extension of them. And that’s how Hal was. It didn’t matter what microphone I used or where I placed it. He always sounded good.”

The basic track had been recorded in stereo to two of the four multitrack channels. Alpert’s harmony trumpets — he played each part — and the trombone were recorded as individual overdubs. To create room for all the horn parts, Levine bounced them back to a second 4-track deck. Alpert’s trumpet was recorded using a Sony C-38 microphone, which the band leader came to regard as a favorite. Signal processing, using mainly the two concrete live chambers of Studio A, was recorded to the tracks for both the basics and the overdubs. That left little to do in the mix, especially because the main mix was in mono, which is what radio wanted, and which was still the best-selling consumer format for LPs at the time. (Stereo records cost about two 1960s-value dollars more.) However, one of Alpert’s favorite parts of making a record was to take the multitrack with him to another studio — usually the Annex — and do the stereo mix himself.

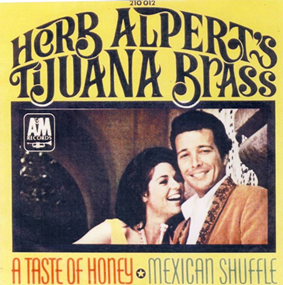

It was yet another quirk of fate that led the song to become a smash hit: Originally, the track was not scheduled as a single at all, but rather as the B side of another song, the famous theme for the film The Third Man. When the record was finished, a B side is actually where Levine thought the track belonged. But it just happened to get flipped over one night by a DJ — not the first time that ever happened, to be sure — and it caught on almost immediately. It eventually made it all the way to Number 7 on the pop charts (while The Third Man theme stalled at Number 47 when it was subsequently re-released as an A side). A little less than a year later, at the eighth annual Grammy Awards ceremonies (in their pre-televised days), “A Taste of Honey” won trophies for Alpert, Moss and Levine. After the ceremonies, Alpert couldn’t resist reminding Levine that the engineer had at one point suggested that Alpert put strings on the track. “So, he laughs and he asks me, ‘Do you still think it needs strings, and do you still think it’s a B side?’” Levine laughs. “But I still think strings would have sounded good on it.”

One final anecdote: It’s been long debated as to what actually drove the sales of Whipped Cream & Other Delights: the music or the now-famous picture of the voluptuous and apparently nude woman covered in simulated whipped cream on the cover. Dolores Ericson has already gone down in history as the model on the cover. What gave her that glow, though? According to Levine, she was three months pregnant at the time.