It’s July 7, and Jenny Lewis has just come inside Capitol Studios after joining Ringo Starr and his pals onstage out front of the Capitol Tower to wish him a happy 79th birthday. So where was that piano she used on her most recent album, the critically acclaimed On the Line?

It’s July 7, and Jenny Lewis has just come inside Capitol Studios after joining Ringo Starr and his pals onstage out front of the Capitol Tower to wish him a happy 79th birthday. So where was that piano she used on her most recent album, the critically acclaimed On the Line?

“Oh, let me show you,” she says, walking around the corner into Studio B, where, inside the room’s iso booth sits the Steinway grand she played; 48 years earlier Carole King recorded the same piano for Tapestry. “That one.”

Fifteen feet away stands Starr, embracing bassist Don Was with a birthday hug, and across the room are keyboardist Benmont Tench and another legendary drummer, Jim Keltner. The band’s all here, in the very room where On the Line was born.

After fronting indie rock fave Rilo Kiley for 15 years, singer-songwriter Lewis released her third solo album, The Voyager, in 2014, and, five years later, this past February, issued its long-awaited follow-up. On the Line debuted at Number 1 on the Billboard Alternative Album chart (Number 4 on Top Rock Albums), and has already made several notable “Top Albums of 2019 So Far” lists. Eight of the 11 tracks were co-produced by Lewis and Ryan Adams, and feature the above-mentioned classic talents (Starr on two tracks, including the hit single, “Red Bull & Hennessy”), with three other songs produced by Beck Hansen.

The openly personal songs for the album, much of which focus on the aftermath of the breakup of a relationship, as well as, later, the death of her mother, were written over several years. “I’m always writing; I never stop,” Lewis tells Mix. The process always involves recording demos, and always on her iPhone. “I’m a Voice Notes addict,” she confesses. “And I’m a Garage Band enthusiast.”

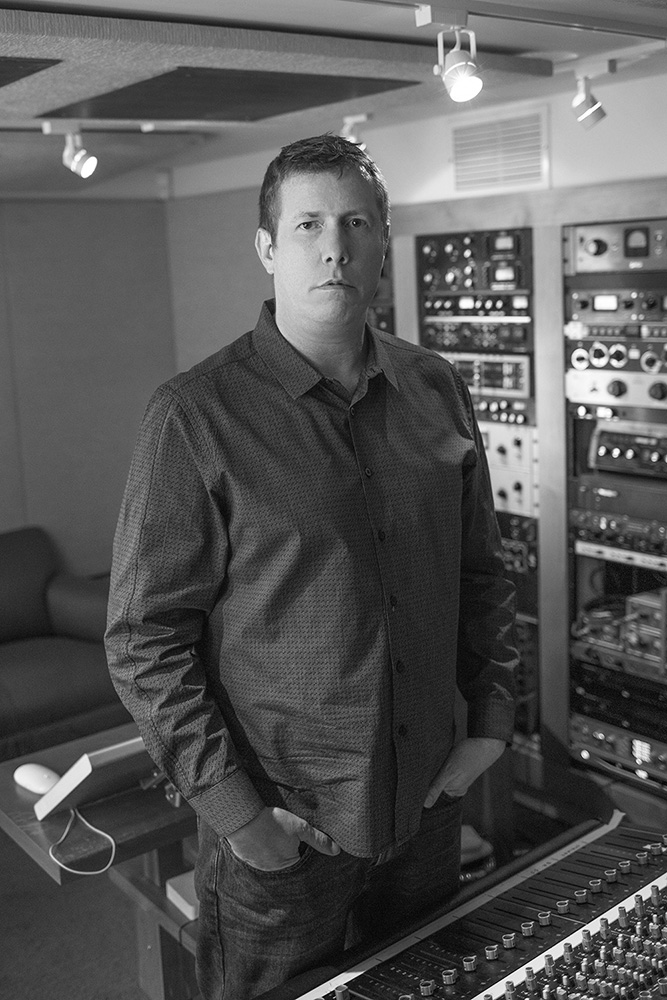

The Voyager originally started out, in 2013, as a Beck-produced album, but continued production with Adams. “She was looking for someone who could give it an old school ‘tapey’ vibe, so someone suggested Ryan,” says Adams’ then-engineer, Charlie Stavish, who, in Spring 2018, moved on to focus on his projects at his studio in Joshua Tree.

In early December 2016, Lewis met up with Adams once again at Pax-AM to record new demos of her songs over several days, with musicians Nate Lotz (drums), Todd Wisenbaker (guitar) and Stavish on bass, developing parts on the go. A total of nine songs were demoed.

Several months later, Lewis, Adams and Stavish reconvened at Capitol Studios, Studio B, to formally record the tracks. Five days’ worth of sessions were booked for the week of March 20, 2017, though the efficient recording band was able to complete the process of basic tracking in just four. “It’s a big deal to go to Capitol,” Lewis says. “That room just resonates. It really informed the feeling.”

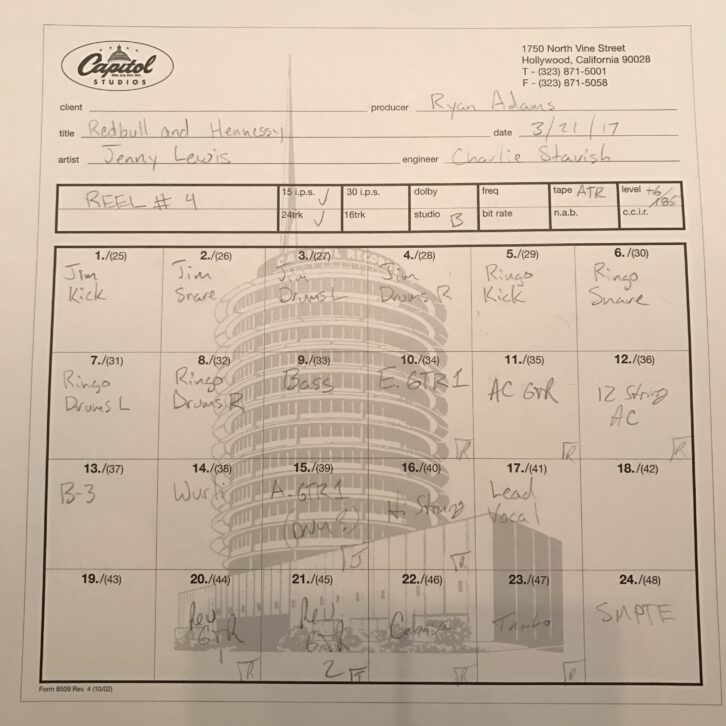

It also offered recording to tape. “That’s always the plan, with all Ryan Adams-related anything,” Stavish says. The team recorded through the studio’s classic Neve 8068 56-input console, to a Studer A827 tape machine onto ATR Magnetics 2-inch tape stock at 15 ips.

For her recording band, Lewis began assembling her “fantasy football team,” as she calls it, with legendary session drummer Jim Keltner. “She’s an amazingly great songwriter, and these songs were so much fun to play—and to listen to,” he says. Once Keltner was onboard, Lewis asked former Heartbreakers keyboardist Benmont Tench. “We used to have ‘music night’ at my house on Sunday nights,” Tench, who also played on The Voyager, recalls. “Her songs aren’t empty; they really feel like they’re about something, and about something personal to her.” Adams played all guitars, and Was rounded out the band. “Don just comes up with these wonderful parts and wonderful tones on all of these songs,” Keltner says.

The studio was set up with (viewed from the control room window) Keltner in the far right corner (the “sweet spot” for drums in that studio), Tench to his right, against the center of the back wall, Was to Keltner’s left, along the right wall, and Adams to Was’ left, just to the right of the control room window.

Lewis herself, it was decided, would shift from guitar, as she was on The Voyager, to piano, and both play and sing live with the band. The Steinway piano was placed in B’s roomy iso both—which Lewis subsequently decorated with candles and other trinkets—to allow for the most separation, as she would be singing live. The piano was turned to allow sight lines between Lewis and Keltner, across the room, something that would prove invaluable.

Stavish miked the piano with an AEA R88 stereo ribbon mic. “I love that mic,” he says. “I have a couple.” Another AEA, a KU4 supercardioid ribbon mic, was placed in front of Lewis to capture her vocals and keep out the piano as much as possible. “That mic is pretty directional. It was pretty surprising how easy it was to get the separation,” Stavish adds. “There’s a little bit of bleed here or there. We had to play a bit with the positioning of the piano mic to get the null point toward her voice. But given the amount of moving parts to it, there’s surprisingly little bleed.”

Keltner offers a rare view into his unique drum kit setup for recording, one which offers him the greatest flexibility. “If it’s a session that I think is going to be fun, and I don’t know that much about it exactly, I will have Ross [Garfield, L.A.’s famous Drum Doctor] bring all my gear and just set up everything.” All have been custom-made for Keltner by DW Drums.

For recording, Keltner will have two kick drums—his primary bass drum, and to his left, a smaller 14-inch. He also uses two different snares, as well as a second hi-hat. “I play multiple hi-hats, and I play multiple snares. If I have it in front of me, I can listen to the song and make a music change right there. What I liked about Jenny’s songs is they were calling out for low tones, to me. Charlie has ears that can hear what I was going for.”

Keltner’s kick drums were covered with E-V RE20s, bused together to a single track; the snares, each with Beyer 201s, top and bottom, and bused to one track, and, again, his favorite AEA R88 stereo ribbon for overhead pickup, making a total of just four tracks. Mixed into that stereo pair was also an AKG 414 covering the floor tom, and one each for the two hi-hats, which Stavish panned hard left/hard right. An AEA R84 was also placed five feet out front of Keltner’s kit, making a fifth drum track.

For compression, Stavish employed either a LA2A or a UA 1176 on the snare, and a GML EQ into a Fairchild limiter for the overheads. He then put the whole stereo pair bus through the GML and then a Fairchild 670 compressor.

Don Was’ old Ampeg bass amp was set up in the upstairs lounge, which overlooks the live room from atop the iso booth; it was miked with a Sennheiser U47 and connected via DI (and bused to a single track on tape).

Tench brought his entire arsenal, though most of his playing centered around his classic Hammond C3 (unknowingly referred to by the rest of the gang as the more common B3). “I’ve owned that since around 1977 or ’78,” he says. “It went on every Heartbreakers tour, and I’ve played it on 99 percent of the sessions I’ve played.” He introduces a distortion pedal in line with his Leslie 147, modified long ago by legendary Hammond tech Bill Beer, a trick he learned from Jimmy Iovine and Shelly Yakus early in his Heartbreaker history. He also brought a digital Mellotron and his Vox Continental organ, as well as a Wurlitzer electric piano.

Tench’s Leslie cabinet was gobo-ed and miked with a pair of 414s on top and an RE20 on the bottom, typically bused all together to a single track (though tracked to an additional pair for stereo for his solo on “Red Bull and Hennessy”). All of his other instruments, the engineer says, were DI’d to a single track, “so that, at any moment, he could play anything while we were tracking, and we’d get it.”

Adams had recently come off the road, so his entire arsenal of guitars was shipped directly to Capitol, along with his pedal boards. His amp, a Benson Chimera, was isolated in a small iso booth built around it and was miked with an AEA R92. While tracking, Adams always played an electric. Any acoustic guitars were recorded as overdubs, miked with a U47.

Tracking at Capitol

The Adams-produced tracks were recorded live as an ensemble—his preferred method, when possible—during the first four days of the week of March 20, 2017, the first being “Wasted Youth,” the album’s third single. The song features a cool signature Mellotron part by Tench on the choruses, supplemented by what Stavish calls “Ryan doing a pedal dance,” producing a variety of guitar sounds.

The second song of the day, the groovy “Hollywood Lawn,” features two key components, including a sliding Keltner drum groove, which “is the thing that sets Keltner apart,” says Beck tracking engineer Darrell Thorp. “He’s not your traditional pocket drummer. His timing…it sways. And when it sways in the right way, it’s just so cool. And very unique.”

The second key component to the recording was the addition of live strings, courtesy of The Section Quartet (several members of which tour with Lewis). “We always wanted to cut strings live; that was always part of the plan,” Lewis states. “We wanted the whole sound in the room.”

The ensemble was set up a little left of center of the room, toward the sliding doors leading to Studio A, contained in a makeshift iso booth. Stavish miked them, once again, with his favorite R88 stereo ribbon, though bused the two inputs to a single tape track, repeating the process for however many overdubs were required to fill out the sound. “We knew we were going to double-track or triple-track, so there was no sense in eating up four or six tracks. So each was recorded in mono on a single track.”

Lewis had always wanted Starr to play on the album’s moving opening track, “Heads Gonna Roll,” something likely suggested by Was initially, but certainly not Keltner. “I don’t suggest anything for Ringo anymore. I get in trouble when I do that!” he laughs.

Starr’s kit was set up in the center of the studio, facing to the right, toward Was. His kit, says longtime drum tech Jeff Chonis, was “what we call the ‘Crystal Kit,’” a Ludwig set covered in Swarovski crystals. The shells are Ludwig’s Legacy Classic shells, a reissue of the classic shells made by the company in the ‘60s, which were a combo of maple and poplar plies, with a reinforcement ring on top and bottom, he describes. “That was Ringo’s sound back then. Now they’re made with today’s technology and a little more craftsmanship. The new ones are put together a lot more precisely, and the bearing edges are better. So they still have that sound.”

The kick drums is 16×24 inches, and the snare, 6.5×14, is Ludwig’s Chrome over Brass, instead of a wood shell. The single rack tom is 9×13, and the floor tom is 16×16.

The tuning, like Keltner’s, is low, but for different reasons. “For Ringo, I tune them in something of a combination of Ringo and John Bonham sound,” Chonis describes, mainly focused on the kick and snare. “The chrome-over-brass snare is something Bonham used on a lot of live shows and recordings. And the 24-inch bass drum is tuned pretty wide open, and it’s just got a little bit of muffling, down in the bottom of the drum. So they’re kind of John Bonham drums, but I tune them for Ringo. So his sound is big, and lots of low end, and very open.”

Stavish miked the kick with an AKG D20, through an opening in the front skin, the snare with a Sennheiser MD-441-U, and his AEA R88 recording the overhead in stereo – making a total of four tracks to tape. Keltner’s 5th mic was dropped, to allow space. “That gave us one back for Ringo, and then we budgeted in three more,” the engineer notes.

Ringo played alone with the band on the album opener, “Heads Gonna Roll,” his colleague and old friend, Keltner, watching from the lounge above. “It’s always a thrill to watch Ringo play —it’s friggin’ Ringo Starr!—one of my favorite drummers in the whole wide world,” he says. “You’re listening to him interpret this song He made history interpreting people’s songs.”

Lewis was having difficulty with the adjustment of her headphone mix during the recording of the track. “I was just playing to my voice, piano and Ringo’s drums. That’s all I could hear,” she recalls. “Then I looked out and said, ‘Oh, my gosh, does this sound terrible?’ And Ringo said, ‘Oh, don’t worry, love, I’m just playing to the vocals. That’s all I need.”

Once completed, Keltner came downstairs and joined his pal for what would become the album’s biggest hit single, “Red Bull and Hennessy,” double drumming as they had in their heyday recording together. “It was one of the coolest things to be able to be in the room and snoop around and check out their gear,” Lewis says.

Of his and Starr’s double-drumming experience, Keltner says, “We do have a very, very similar heartbeat,” Keltner explains.

The Beck Sessions

For the remainder of the year, Lewis took a break, spending her time “writing and floating,” as she says, moving about from New York to Nashville, and eventually back to L.A., where her mother passed away in late October 2017.

She realized that the album was still short several songs, and, having worked with Beck at the beginning of The Voyager, she did what one does when trying to reach the producer. “I sent him a ‘Bext.’ That’s what you send Beck!” And not long after, she forwarded her iPhone demos of the three tracks.

“She had already pretty much recorded the record, but she needed help finishing it,” the producer says. “I just knew, ‘This one’s an important one.’”

Upon hearing the three demos, Beck notes, “They had this otherworldly sound, the kind of thing you would hear on some record long ago, where they discovered some demos from a lost band that were never released. But they had a ghostly, spooky quality to them that I really liked. And I used it as a guide and a compass on the feeling I wanted the songs to have.”

Beck’s approach was quite different from that of Adams. “Beck is very meticulous,” Lewis notes. “He got into the structure and chords of the songs. He really gets into the arrangement, which I was open to.”

The team returned once again to Capitol Studio B, something Lewis was adamant about, and, with one exception—Jason Faulkner—this time she didn’t play an instrument.

Recording sessions took place on February 6-7, 2018. As is his usual practice, Beck worked with tracking engineer Darrell Thorp, while another engineering partner, David Greenbaum, worked on the back end to manipulate and craft the tracks. Thorp recorded to Pro Tools, instead of tape, to allow Beck and Greenbaum to perform whatever manipulation they would be pursuing “in post.” Thorp set the room up the same as the sessions the year before.

Keltner returned for the Beck sessions. “He has a really distinct feel, a kind of iconoclastic looseness. His instincts go places that not a lot of people know to go,” Beck states.

Beck’s approach to tracking often involves two different sets of drums: Keltner’s own kit, in the live room with the other players, in the same far-right corner as before, and another “lighter, funkier kit,” says Thorp, “in the iso booth, with no room mics, no reverb on it—just dead dry.”

Beck would do several passes with the band, with Keltner in the live room, and another pass with the drummer in the iso booth, playing to a click, his other pass muted. “There are a lot of great takes and versions of these three songs,” Beck explains. “And for all the tracking I ‘ve done over the years, the little room always wins, for the drums.”

Thorp miked Keltner’s own kit with a U47 FET on the kick, SM57s (top and bottom) on the snare, an AKG C451 on the hi-hat, and an AKG C12A on his toms, with a single U47 covering the overhead.

Faulkner, positioned to Keltner’s left, where Was had been set up, would always track playing bass, immediately recording his guitar parts afterward. Though he does bring a Fender Precision, on these recordings he played a more diminutive Fender Mustang with flat-wound strings, through an Ampex Portaflex B-15 amp.

“Jason’s not a big dude, so he doesn’t like playing a long-necked bass,” Thorp explains. “But that Mustang delivers deep, rich bass tones.” Adds Beck, “It has a rickety sound, especially with those flat-wound strings. It just instantly sounds like a cool old record.”

For guitar, Faulkner plays a black ‘70s Fender Telecaster or a mid-‘60s pink Fender Jazzmaster, though he tends to favor the Telecaster, Beck says. While a guitar station was also set up for Beck, he tended to stay in the control room and focus on structuring the song, recording any parts he wished to add later.

Tench played his Hammond C3 again, though Thorp applied his own technique to the Leslie cabinet. “I don’t do the traditional two mics on the high rotor, in the little cave, and then a mic on the low rotor,” he explains. “I learned from an engineer long ago to place a pair of large-diaphragm condenser mics, like U87s, pointing toward the edges on opposite sides, so that you get that left and right image.”

Lewis was set up in a gobo-ed vocal booth, singing live into a tube U47—a favorite of Beck’s. “It’s something I always go back to,” he says. “I’ve tried modern mics, but, in a shootout, the U47 always wins.”

Three songs were recorded over the two days at Capitol, “Little White Dove” perhaps the most personal and moving, even with its hip groove. “It’s probably the funkiest song about losing a family member,” Lewis states. “I wrote that visiting my mom in the hospital every day, trying to get up the courage to go in there. And this bass line was just in my head as I would walk down the hall.”

She would stand beside her mother “and she would harmonize with me. I don’t know if she was conscious or if she understood the song, but she was still present—harmonically very present. And her harmonies were perfect. She was out, but the music was still in her.”

The song begins with an always-treasured Keltner count-in, with Tench on his C3 and a stirring live vocal from Lewis. “The takes she was doing that day were just really, really fierce,” Beck recalls. “I think we kept quite a lot of that.”

The song “Rabbit Hole,” Beck says, “started out with a mandate of sort of a Traveling Wilburys, Jeff Lynne approach, with the drums from the big room. But once we did that, she felt it wasn’t right, so we had to kind of pull it back. It was kind of a windows down, out in the car on the weekend song—classic California, Petty, Sheryl Crow kind of song production. Then we did some other things to take it a little stranger. It ended up with an epic album-closing sound.”

Once the basic tracking was completed, Beck and Greenbaum began crafting the songs the producer had been hearing in his head since the beginning. “We’d essentially record the song in a basic way, true to her demo,” Beck explains. “Then I could go off and pull it apart and throw a bunch of different ideas on it, different keyboard melodies.”

“They just kept growing these songs,” Lewis says. “And with each step, I just loved hearing the songs mature in that way. It was like Christmas every day, when I’d wake up and get a new version from Beck.”

Mixing It Up

As Beck was continuing his work with Greenbaum, remix engineer Shawn Everett started on the Adams-produced tracks. Everett’s process typically—and unbeknownst to Lewis—involves his own first pass at mixes, based simply on his own instincts

“His first pass scared the shit out of me,” Lewis says. “When I got it back, I cried!

“I didn’t understand his process. His first pass is completely out, and then you have to kind of bring it back to center with him. This was fresh, and it was new, and it wasn’t something I had heard before, in the context of my songs. So with a little support from Lenny [Waronker] and Beck, I understood what Shawn was going for. And I trusted him from that point forward.” Lewis started coming to Everett’s studio, and the two began working together. “Shawn and I just started carving,” she says.

Everett’s process began with Keltner’s drums, targeting the kinds of low frequencies present in Roland 808-type samples. He might re-amp the recorded kick drum in his cavernous studio live room, while placing another kick drum in front of the loudspeaker. “And I don’t mike that drum—I mike the room,” he adds. “This allows me to single out a particular drum mic, and do it only with that.”

The double-drumming on “Red Bull and Hennessy,” he says, was “a different situation than most of the record. As soon as you have two drums, you have to treat it in a different way. Plus, it’s a rocker. Normally, on a track like that, you’d have the drums really punchy and pushing, which is something you can’t quite do in the same way when there are two drum sets. It has to feel punching and aggressive, but with more of an orchestral image.”

For Adams’ guitars, he says, “His tone was pretty much there to begin with. If anything, I would run it through another layer of some kind of harmonic content machine, maybe a level locker, like a [UAD] Thermioinic Culture Vulture. Just to pull out any kind of cool grit inside of the tone, and add to it a little bit—use something in parallel to the clean mic, just to make it gravitate a little more toward the center of the recording.”

On Tench’s parts: “Whenever I was hearing a B3, I was keenly aware that it was him playing it. He was speckling all sorts of cool stuff across those recordings. Just a great texture to work with. I think on my first pass, I went really wild and was doing all sorts of crazy stuff with his B3. At one point, Jenny just said, ‘Look, you could make it sound like a B3. Can you do that?” he laughs.

For Beck’s tracks, Greenbaum would provide a new Pro Tools session to Everett, incorporating their changes as if they were live, including effects and EQ. “We’d do that for his clarity, so that you can’t even see that something was muted on our end,” he explains. “It’s just a completely remade session. It’s very different than what we got from Darrell.”

Making those tracks fit in nicely against the songs Adams produced took a special touch, Everett says. “They were recorded in such a different way. So the approach, in my mind, was just a matter of bridging it a little bit.” He completely avoided his re-amping technique on Keltner’s drums for the Beck tracks “because the approach of the drums on his recordings are so different, a much more punchy, close, dry sound.”

One thing he was certain to include, on “Little White Dove,” was one of Keltner’s trademark count-ins, heard throughout history on important rock and roll recordings. “His count-ins are kind of legendary,” Everett says. “If I ever find them on a track, I never want to get rid of them.”

Of Everett’s work, Lewis notes, “Shawn is a modern master. The record sounds the way it does because of a group effort, but he really changed it into what you hear. It’s incredible. I started out as an artist, as a child, just trying to be perfect. Trying to be someone else. That’s a training I’ve been fighting against ever since—being fucking perfect and playing characters. And it’s taken me about 20 years to get back to myself. And thanks to these amazing people, that is what you hear.”