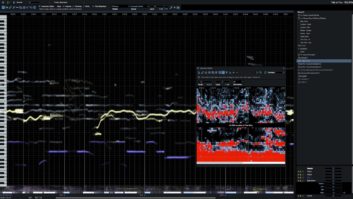

Photo: Dinesh Booz, sweetsoundnyc.com

Following Musical Passion Where it Leads, From New Order to Game Rebellion

Mixing engineer Hernán Santiago lives for music. Even more than most engineers, he has made it his life’s passion to study, consume and devote himself to understanding how music is created—from rap to dance hall and pop to rock and more.

As one of the only kids in the south Bronx to idolize New Order at the time, career training included making his own beats and hitting the clubs. Later, he took classes at the Center for Media Arts (from Mix’s own Steve La Cerra!) but dropped out, opting instead to do hard time as an

intern before making his leap to assisting in 1995. Always one to take initiative, Santiago watched session after session and, over the years, compiled other engineer’s tips and techniques into the ultimate black book, which he dubs “his training manual.”

Currently working in the Yonas Media East studio, which is owned by Ben Yonas, the owner of Coast Recorders in San Francisco, with an unsigned band by the name of Game Rebellion (www.gameforlife.com), a rock/hip hop band he calls authentic and earnestly admits is “the second-best project” he’s worked on in his life, as well as on a project with actor Richard Belzer (who is doing a Dylan covers album in electronica form), Santiago sat down with me to talk about his experiences in the New York studio scene.

How did you get started in the industry?

I started out at a studio called Platinum Island Studios in Manhattan [in 1994]. I went to

the Center for the Media Arts. My teacher was [Mix contributor] Steve La Cerra. I dropped out; it was an eight-month course, and I dropped out at five months. I was already interning before I was going to school and then I got hired as a GA (General Assistant). I was doing eight hours at a supermarket and interning at the studio for eight hours. I was working at the supermarket supermarket one night when the studio called me up [and asked me] to [be] assistant engineer to Positive K, a rapper who had a hit, “I Gotta Man,” during that time, so I had a choice to make: Quit the market, or go do the session. Of course, I picked the session! [Laughs] That’s how my career started.

I was hired as an assistant, and then after that I went back to interning for another four or five months. [Laughs] But I was getting paid minimum wage at the time. I was just hanging out there and met a lot of incredible engineers. I’d keep notes of everything we’d do. I kept a black book, and instead of phone numbers, it had every detail of every engineer they assisted. It¹s its own training manual‹this engineer used this microphone with this kick, this engineer used this microphone with this kick, what makes it sound better, when to use this preamp or compressor, mic, EQing—stuff like that. That’s how you do it.

I never worked in one studio; I always worked with successful producers that had their own studios, so from the 90s up till now I was freelance. For some reason, I ended up working for producers for four years in a row. I went from there to Manhattan Beach

Recording (www.manbeach.com), and I had to intern again. In my career, I’ve interned three times, but that’s okay: I do what I love. [Manhattan Beach Recording] was a jingle house. That’s where I learned about jingles, horn sections and live stuff, really. I was there three years. That was a cool studio. And that’s where I started finding about acoustics.

Who have you been working with recently?

I worked at Avatar last spring. I was mixing the [rapper] Shine’s project there. It was some intense stuff, in duration and the scale, because he’s in jail. So we were trying to record vocals and have to approve every mix, and we’d have to call him at 9 o’clock, 10 o’clock in the morning and be at the studio. [There was] recall after recall after recall after recall [because we were taping vocals over the phone]. I did, like, 30 versions that never made it.

I worked all summer long with Ice T. He’s a funny kat. He did a rap album and Body Count’s new album. There’s another band I’m proud of working with called Spank Rock. They’re coming out in January also. That rap group, they’re from Baltimore, and they do Baltimore booty music. These guys, they basically gave me the project and said, “Hernán is mixing.” We recorded it, we produced it. Then they didn’t show up to the studio for two months. I did whatever I wanted to do to the songs. They were the ideal client.

How do you work with so many different kinds of artists and styles, but come off as authentic?

I’m an engineer—simple. I grew up in the south Bronx, so hip hop was in my blood from day one. But then, when I was 17, I ventured out into The Village and I ended up going to rock clubs and I’m kind of multicultural. My favorite band is New Order. I love New Order; Jesus Christ, do I love New Order. That’s who I want to work with, to be honest, before they retire. That’s who got me into music. A friend introduced me to their song called ”Perfect Kiss,” and I’d never heard anything else like that before in my life. Once I listened to that, it opened my mind up completely.

Can you tell me about your mentors?

There are so many! The first person that influenced me heavily [was at] Northcott productions, and the owner was Tommy Musto. I left Manhattan Beach Recording to work with him at a dance music label, they also distributed vinyl, and this guy taught me everything about making records: editing, arranging, programming, synchs, drum machines, et cetera.

Character Music Productions was an important period, from 1998 to 2002. That’s where I learned my R&B skills. I worked with two great producers there: Troy Taylor and Charles Farrar. I was there chief engineer for four years there, and worked with many great artists, including Faith Evans, Mary J. Blige, Ronald Isley and more.

There are so many! The first person that influenced me heavily [was at] Northcott productions, and the owner was Tommy Musto. I left Manhattan Beach Recording to work with him at a dance music label, they also distributed vinyl, and this guy taught me everything about making records: editing, arranging, programming, synchs, drum machines, et cetera.

Do you have a signature sound that you bring to your projects?

I worked with Channel Live, and they wanted the house music sound, because they thought of me as a house producer. [Laughs] I said, “I don’t understand; don’t you want a hip hop sound?” And he said, “No, I want the kick big and everything big!” Then I figured it out. What I do is [take techniques associated with certain styles of music and put them into a new context in another style of music]: I would do something like some delay echo stuff that you would do on a dance record, oversaturated. I would do that on a hip hop record, on an R&B record, on a rock record.

If Game Rebellion keep me [when they get signed], I want to record them in Avatar in straight-up analog. They have a Neve 8068—old school, and one of the best-sounding live rooms in the world!

To nominate your favorite regional engineer for a profile in “Generation Mix,” please e-mail [email protected].