Sean Penn (center) stars in Van Sant’s portrayal of the late Harvey Milk.

Photo: Phil Bray

Gus Van Sant has long been one of America’s most daring and creative directors, deft at depicting the complexities of the human psyche. A critical darling since his moody 1989 breakthrough film, Drugstore Cowboy, Van Sant has occasionally flirted with the mainstream, too, though always on his own terms: Goodwill Hunting (1997) was a huge hit that earned nine Oscar nominations; Finding Forrester (2000) was also successful. His films since then have been less commercial, including Gerry, Elephant (inspired by the Columbine killings), Last Days and Paranoid Park — little films that pack a big emotional punch. Van Sant’s latest is a return to “bigger” films, but is no less brave: Milk tells the saga of Harvey Milk, an openly gay member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors who was assassinated along with mayor George Moscone by a political rival in 1978. Sean Penn stars in the title role of this film, which was partly shot on location around San Francisco, including City Hall where the murders took place.

Dating back to Even Cowgirls Get the Blues in 1993, Van Sant’s primary collaborator on sound has been Leslie Shatz (whose career goes back to Apocalypse Now), and the two have gone down some interesting sonic roads. Shatz says, “Gus wants to do things in the most unconventional way possible. He loves to experiment and he is full of ideas — about sound and everything else.”

Shatz acknowledges that the overall approach to Milk was more conventional than on some of Van Sant’s other films, but it was not without risks, even when it came to the all-important production dialog tracks. Spearheading that end, as he has for Van Sant’s movies since Gerry in 2002, was New York-based Felix Andrew, who has made a fine career working on indie features and documentaries — mostly as a production mixer, but also editing, working the camera, even directing.

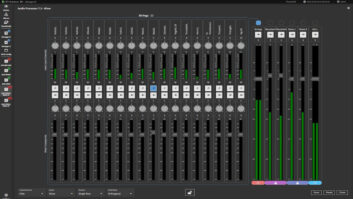

“The great thing about Gus’ films is they are all incredibly collaborative,” Andrew says. “On the sound side, Leslie Shatz is always very involved and totally responsible for the post-production elements [he is both sound supervisor and a re-recording mixer working out of Wildfire Post in L.A.]. But Gus and [cinematographer] Harris Savides also contribute to what we do, and I also have a very close collaborator on the production side, Neil Riha. Often, we’ll both be running separate rigs, and he and I both boom scenes, as well; sometimes we run two booms. We also had a third on this film — Mike Primmer — who did some booming and various tasks. It was very fluid, always changing depending on where we were shooting.”

Though Andrew says that Milk was more of a “studio film” than Van Sant’s lower-budget efforts, he still likes to bring techniques he learned in the documentary world to every shoot. “Documentaries teach you to work with what you have and to work with less, and Gus’ filming environments are conducive to that aesthetic,” Andrew relates. “We always try to be open to what might happen and we try not to have a lot of gear and people around. I like to be very mobile, so a lot of the time I don’t even work with a sound cart. We recorded Milk on two Sound Devices 744s, literally over the shoulder for most of it.” For mixers, Andrew and Riha carried Sound Devices 442s. The RF mics were Lectrosonics Digital Hybrids.

One unusual production sound choice was to have the primary boom be stereo — Andrew suggested a Shoeps M/S mic. “The M/S technique has more of an ambient feeling than a left/right feeling,” Shatz says, “and it worked well for Elephant because they were shooting in high schools and I thought it would preserve the acoustic feeling of the hallways. Gus really liked it because it produces this spacey, almost psychedelic feeling.” In Milk, he notes, the M/S approach added dimensionality to the crowd scenes.

“It’s a hassle for Felix,” Shatz continues. “He has to boom and lav everything, and it’s a hassle for me [on the mix stage] because we’re using the lavalier in the center and the M/S on the sides, but you have to carefully calibrate how much M/S-to-mono you use, and what the spread of the M/S is.

“Also, with M/S mics there’s a lot of low end and noise we have to get rid of, and for ADR it’s insanely difficult to match. If you’re putting an ADR line in an M/S scene, you have to have M/S ADR, too — you can’t suddenly have it collapse in mono. But ADR stages have no acoustic color, so we were faking it in using a [Digidesign] TL Space reverb. Next time we’ll ADR in a more acoustic location.”

“A lot of directors want a straight, clean mix and that’s fine,” Andrew adds. “But Gus is always looking for other kinds of experimental tracks that have a different sort of feel. That’s why his movies sound different than other people’s.”